1.

We both had trouble, in our wedding vows, coming to the point. Our loved ones grew bored, threw pens at us, groaned when we kissed. Then we were pitched off to some squiggly beach, where the staff kept us half-asleep with drinks the texture of baby food, but ice-cold and walloping. The squat glasses sweated in our hands. And then we were back inside the apartment we already shared, tan and blinking.

Marriage has turned out to be a worsening of that return.

Our friends are impressed by how long we’ve managed to keep a straight face.

Years.

2.

My husband is a small-time movie director. He used to want to be more, but he’s successful within this cinched ambition. His films have a “documentary feel.” It’s not his fault. All we can afford is what’s already there.

I’m in a number of his movies accidentally. I’m told it adds pathos. You can see me at the edges, unframed, frowning over a bowl of salad or absently folding some shirts. Sometimes I’m talking on the phone, but when I see it now I can’t remember to whom. I’m not a character: I don’t have a name. See, our apartment is tiny, so our lives have to happen in stacks. I wasn’t meant to be in these movies. I was only in the only place at the only time.

3.

Five or six years ago, my husband and I witnessed a beheading. We were having sandwiches at a just-lunch place, with a patio overlooking some chunked-out green. There was a fidgety creek through the grass, and birds in the creek. This nice area was overcome in the end by the Interstate. It was charming right up until that last moment.

We heard somebody next to us shout, “Whoa, whoa, whoa, hey!” the way you would to a toddler, then stand up and point. Beyond the green, we saw a motorcyclist skidding out of a turn so acute that he was nearly lying down. Then we heard the little pop.

The pop was his head coming off against a concrete barrier. The sound had been shrunk by distance. It must have been much more awful up close.

My husband ran to the trunk of our car and grabbed his camera, then came back and started recording the crash. “Is that for the police?” asked our waiter. “No, I’m an independent filmmaker,” my husband said. That lost us the respect of everyone. They ignored us for the rest of the crisis. We’d given up our “in” with them, which we’d acquired by accident, through the sheer luck of shared witness. Anyway, the footage wasn’t good. It was all too small. You couldn’t even see the head.

How did my husband plan to work this crash into one of his movies in the first place? They’re comedies, mostly, about couples like us, starring our friends.

But that’s what I remember. Like a cork: pop!

4.

I was getting rid of some old clothes when I came across a manila envelope full of letters between my husband and a woman named Valeria. In them, I caught him dilating upon a slew of topics I didn’t even know he knew about: oppression, exploitation, “just unrest.” He was outlining the whole social history of Valeria’s country; he seemed to want to impress her with his appetite for study when it came to all things Valeria. But the product of this was both gushy and vain. Embarrassing. It was easy to read his real interest, which was carnal, puckered. Every page was a spill of clotted desire.

For me, it took a few minutes to click—Valeria! She’d been an off-site tour guide at the resort where we spent our honeymoon. My husband had been interested in her then, too, at least to the point of learning and repeating her name. In the letters, he was still doing it: “Valeria, Valeria, Valeria!”

The final note was from her, and explained how he’d gotten his hands on both sides of their conversation. Valeria was trading him up for somebody real. Someone close by, her own age, who spoke her language, and whose knowledge wasn’t so flaunting and thinly learned. She was returning his letters with a terse, “Thanks, and good luck.” It read like a job rejection. When I read it, I couldn’t help myself: I honked.

When I mentioned these letters to my husband, he seemed mortified at first. He stayed in the bathroom for about an hour. Then suddenly he burst out, seeming fine, and asked if I would prefer it if he kept the letters someplace else, like the garage. It was not a problem, he told me. Whatever. My choice.

5.

I almost forgot to mention the time I was eleven and saw a pair of whales breaching. I watched them with my class from the back of a boat. The whales looked like two souls flung up and spun. But the souls of whom—or what? In any case, I was enraptured. It lasted five minutes, then the motor kicked on, and the gas smell put me in mind again of the city and school and my small, hurried life.

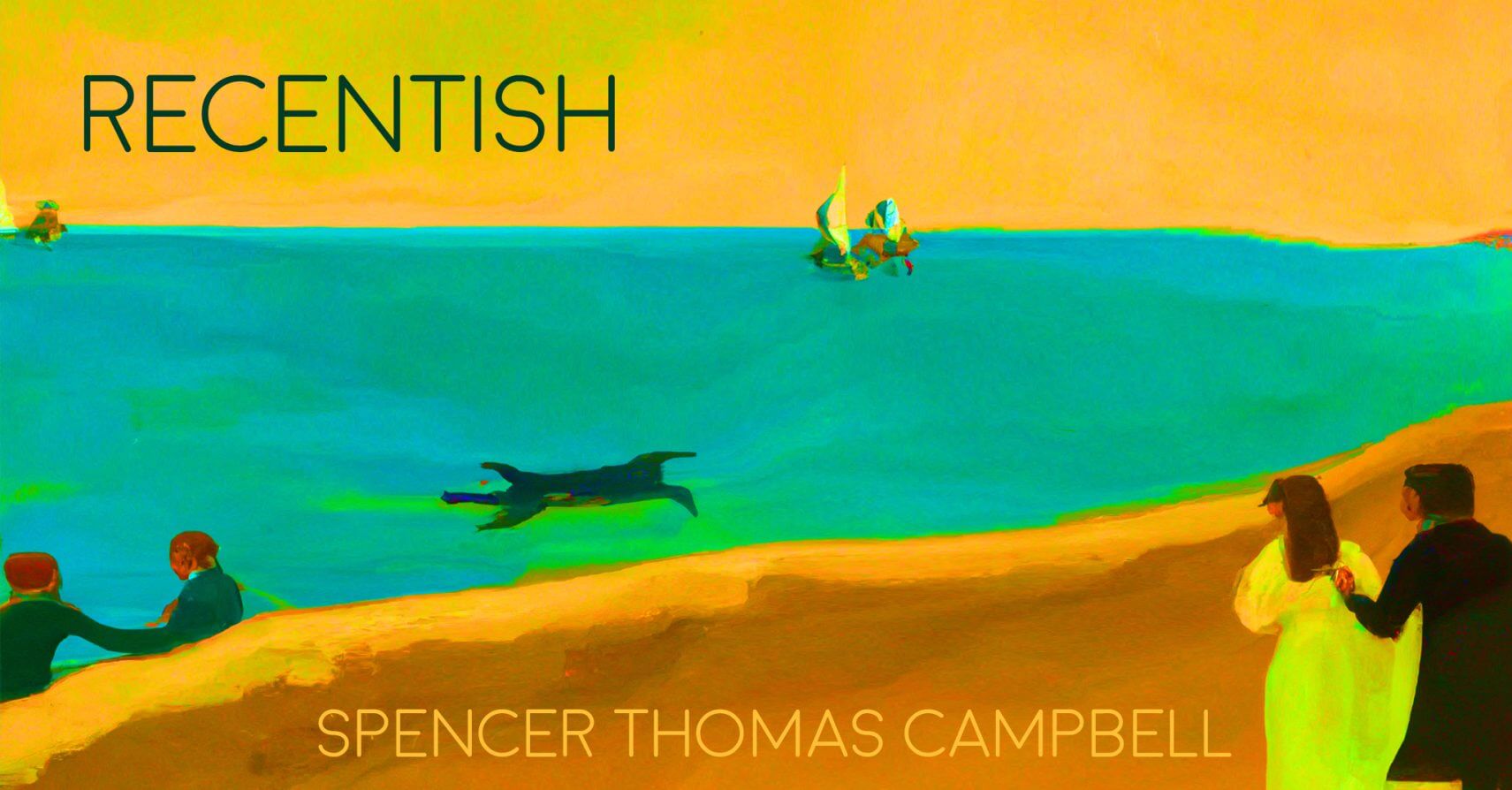

I’m told there is a movie of my husband’s I’m in—recentish—and that for once I come across as something to behold, but I can’t see it.