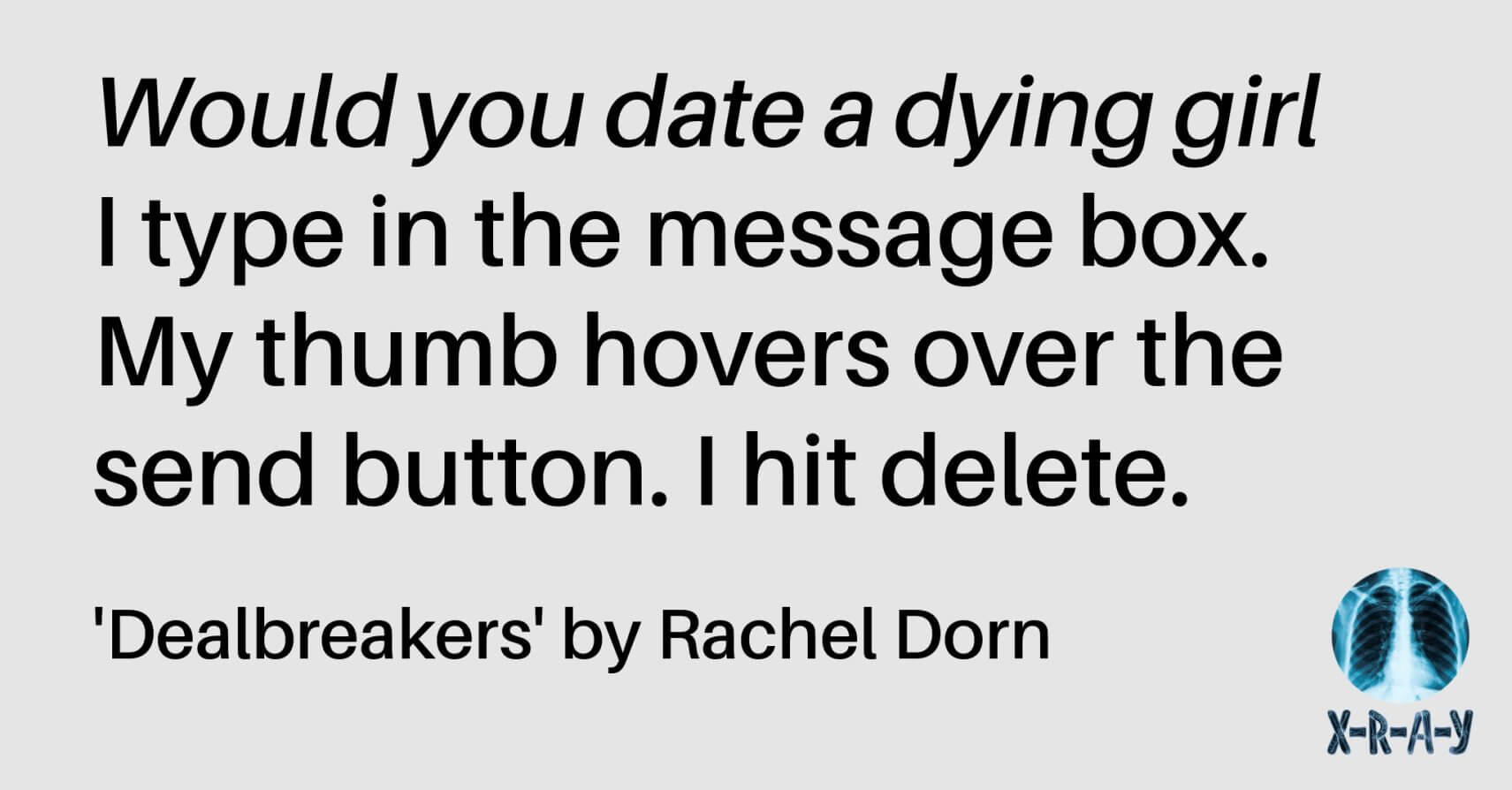

Would you date a dying girl I type in the message box. My thumb hovers over the send button. I hit delete.

What are ur dealbreakers I type instead.

****************

We don’t say terminal anymore, Janessa, my support group leader, says on one of our monthly Zoom calls. We say incurable. Because, you know, people can live a long time with this now. What doesn’t need to be said is that not all of us will.

****************

In the months after I find out I have an incurable heart and lung disease, I spend a lot of time thinking about a man. All my journal entries mention him. I spend pages dissecting our FaceTime calls, the look he gives me when I say I have to go, his insistence that I call him right back, trying to mine for proof that he really loves me. That I am still lovable, despite this.

*****************

When I met T, a few months before I got sick, I Googled his name. The first result was a missing person report from several years earlier, accompanied by a thumbnail photo of him smiling in a black sweatshirt. Last seen in the Pine Bluff area on October 31st, the caption said, anyone with information about his whereabouts please contact the Pine Bluff Police Department. I took a screenshot and sent it to my friend: is this a red flag

*****************

The heat in my apartment went out for three days the winter I met him. It was as cold as a Minnesota February gets; I’d been sleeping in my heavy-duty down coat and two pairs of pants, creating a ring of space heaters around my bed. He lived an hour away, across the Wisconsin state line, but he told me he’d come lift my spirits and he did. It was snowing; we ate takeout tacos in bed, drank bubbly from the bottle, curled together under the covers watching The Sopranos on my broken laptop. My bedroom was all windows—nine of them—and I always said it would be the worst place to be if a tornado struck in the night. It was the best place to be when it snowed.

*****************

T made it clear from the start that he was someone who could never be pinned down. The attraction was undeniable, but it was our conversations that thrilled me–a nonstop game of verbal ping pong. I remember thinking I could banter with him for the rest of my life and never get sick of it. At the end of a weekend together, I found a little baggy of mystery pills in the drawer of my nightstand—Valium, maybe, left there by another man—and offered them to him. He swallowed a handful all at once and left. A couple hours later he called me. I’m fucking floatingggg, he said. And that’s how I felt too. Like I was floating.

*****************

T FaceTimes me from a hotel in Los Angeles. He FaceTimes me from a hotel outside of Ruston, Louisiana. He FaceTimes me while driving a Benz through Cherry Hill, New Jersey. In the wake of a breakup with another man, too sick to do much of anything, I’ve moved in with my retired parents. I answer his calls in my childhood bedroom with its teal walls that my sister and I painted when we were kids and our mom never painted back. I live my entire life between these walls now. You gotta get better, he says, so you can run around with me.

*****************

Out of boredom I download a dating app, then delete, then redownload. I’m swiping past people who are doing everything I can’t do; looking for a woman who can be someone I’ll never be again. An adventure partner, a travel buddy, someone to hike the Pacific Crest Trail with. How do I tell them that the most adventurous thing I’ll ever do with them is meet them in person?

*****************

I match with a cardiologist on one of the apps and when he messages me I say I wish my cardiologist looked as good as you and he says lol do you actually have one and I say yeah and he says oh dang do you have an arrhythmia or something and I say nah, pulmonary hypertension and he unmatches me. Relax, I want to say, it’s not contagious.

*****************

I have to call an ambulance one afternoon in July, after the diagnosis but before the meds start working, because my heart is going berserk. 180 beats per minute and I’m struggling to breathe. Four EMTs show up to my parents’ house and one of them is the hottest man I’ve ever seen. In the back of the ambulance I accidentally flash my tits to all four of them while they’re hooking me up to the heart monitor. It’s SVT, one of them says to the others and then the hot one hands me a syringe and tells me to blow into it. We’re gonna go fast, the driver says, turning on the siren as we bolt through the streets of Saint Paul and I’m on a stretcher, blowing into the syringe, over and over, and the hot one tells me I’m doing great and squeezes my hand and I’m thinking am I going to die in the back of this ambulance and I’m thinking this is the most humiliating moment of my entire life and I’m thinking I wonder if he’s single.

*****************

When I tell the men from the apps that I have pulmonary hypertension, after a perfunctory that sucks, I’m sorry their responses depend on whether or not they’ve heard of the disease. If they have, and they know a little bit about it, they invariably ask if I take Viagra (yes, three times a day) and if it you know…does anything (no, not in women). If they don’t know anything and I explain that it’s a pretty debilitating heart disease, they want to know if I can still engage in, um, activities (maybe, not with you).

*****************

I read a New York Times article about dating with chronic illness and then I read all 277 comments. I’m looking for recognition, some confirmation that I’m not alone. In the midst of people proclaiming that essential oils cured their husband’s chronic Lyme and others arguing over the right time to reveal a disability, a woman with a rare blood cancer shares a story about a date she went on. When she mentioned to her date that sex was risky because an infection could kill her, he was convinced she was exaggerating. He told me he felt so sorry for me that sex could prove problematic, but never mentioned that he felt sorry for me because I had terminal cancer…it soon became apparent that he would rather have incurable cancer than not be able to have sex.

*****************

I wonder if it’s best to play my cards up front, to let them know what they’re getting into before we even match. In my bio I write I have a terminal illness, looking for my A Walk To Remember arc. Then I wonder if this defeats the purpose; anyone who’s seen it knows that in that movie Mandy Moore’s character doesn’t reveal she has leukemia until the boy has already professed his love for her.

*****************

Over text, T and I reminisce about the bad emo music of our youth. He was a star football player in his small Louisiana town, I was a bookish Catholic school girl, shivering in my uniform skirt through long Midwestern winters, but our short-lived emo phases somehow synced up. Remember this one? He sends me a voice note, serenading me, screeching the words to Your Guardian Angel by The Red Jumpsuit Apparatus: I will never let you fall / I’ll stand up with you foreverrr / I’ll be there with you through it allllll

*****************

We all have our baggage, my therapist tells me. I don’t think it makes you undateable. I’ve put on makeup, for the first time in weeks, to meet her in the portal. She starts talking at length about her husband’s struggle with addiction, about how you never really know what you’re getting into with someone anyway, because things change. I look past her, fixating on the unmade bed in the corner of her screen. If you don’t know, you don’t know, but if you do know, you can avoid it, right?

*****************

I ask the girls in my support group what they do about dating. A lot of them are married and I secretly resent them, but a few of them are single. I don’t, K says with a laugh. She’s the one I relate with most: we’re both in our early 30s, both had to move back in with our parents, both got broken up with by our boyfriends when we got too sick. Maybe it’s possible to have a partner that sticks it out with you, if they love you enough, but getting someone to sign up for this, well, it’s just a whole different thing. Everyone agrees.

*****************

T slipped out of my life as quickly as he slid into it, that first winter. By the time I heard from him again I had a new boyfriend and a mystery illness. I told him about both. Our friendship rekindled, but I kept him at an arm’s length, trying to dim the switch on that light that came on inside me whenever we talked. He was moving out east soon and wanted to see me before he left. I said no, I can’t, I’m with someone. When I started to feel the cracks in my relationship deepen, I told him that too. I don’t think he loves me, I said. Well I love you, he replied.

*****************

In the aftermath of my diagnosis, I tell T that it’s been proven that women who become seriously ill are more likely to be left by their male partners than the other way around. That’s bullshit, he says, most divorces are filed by women. Not in this specific scenario, I say. Men don’t like to be caregivers. I sent him a link to an article about it; there’s a picture of the baseball player Albert Pujols, who left his wife after she had brain surgery. That doesn’t count because he’s famous, he says. I say okay and send him another article about women with terminal cancer being left by their partners. You don’t have no cancer man, he says.

*****************

Months earlier, while still searching for answers, I read Meghan O’Rourke’s The Invisible Kingdom, which chronicles her own diagnostic journey with a complex chronic illness. She talked about the shame, as an ill person, of needing other people so much, both in concrete, material ways, and in the need for recognition. I felt a profound sense of betrayal that he did not seem to feel the urgency of my suffering, she wrote of her husband, who rarely accompanied her to doctors’ appointments. It is hard to be the partner of someone ill, at once close to the problem and permanently on the other side of the glass from it. I read these words at night, next to my boyfriend, B, who was trying to understand, but who would always be on the other side of the glass.

*****************

A month and a half before I got diagnosed, when I was too weak to walk up the stairs to my apartment and didn’t know why yet, B dumped me. It sounds bad, to say it like that, because by then I didn’t blame him. It was my idea. I could tell he felt trapped but was afraid to abandon me, so I gave him permission to and he took it. I was already sick when we met a year earlier and had spent a good chunk of our year together searching for answers—in the fluorescent light of dozens of exam rooms, in the test results tab of my MyChart app, in the archives of niche Reddit forums. Our whole relationship felt like a series of things I wanted to do, but couldn’t, while he hung around on the sidelines of my pain feeling helpless. We might have been right for each other if we’d met under different circumstances, if I’d gotten better instead of worse. But we didn’t, I didn’t. I was heartbroken for a week, and then I was too sick to care.

*****************

In the week between when we decided to break up and when he moved all of his things out of my place, we had sex one last time. For closure. The whole time I wondered if it would be the last time I ever would.

*****************

The thing that nobody warns you about having a heart disease is that it makes it impossible to **** ***, I tweet. I consider bringing this up with my cardiologist, but decide I would rather die horny than tell a 75-year-old man what my heart does when I get aroused.

*****************

A popular Instagram fashion brand is advertising a tiny brass pill canister embossed with the word Viagra. The algorithm shows it to me over and over until eventually I buy it. Beautiful women take Viagra has become my little motto, my bit with friends and family whenever I pop one in their presence. If I’m going to be taking it for the rest of my life, I might as well own it.

*****************

T tells me that before we can have sex again he needs to see me run a mile. Or do a power clean. Your choice, he says, but I’d go with the mile. Less blood pressure action. I know he’s joking, but I know there’s a deeper part of him that’s a little serious. Okay coach, I say. I don’t want to tell him that these things still feel so out of reach.

*****************

Maybe, I think, the reason T is so important to me is because he was the last person to meet me when I was still healthy, the last person who would ever get to know the version of me that could pop a bottle of champagne after midnight and drink the rest on a lazy Saturday morning, the version with energy and verve and dreams for the future, that could plan a trip to Palm Springs on a whim, that didn’t have to take supplemental oxygen on the plane, that didn’t have to take pills four times a day just to stay alive. The version that could get high without sending my heart into overdrive, that could fuck without sending my heart into overdrive. That could do a power clean, or run a mile, and not think twice about it.

*****************

By late August, the meds are starting to work. I can go on walks again, slowly, in the sticky heat. Senator Amy Klobuchar tweets a picture of herself at the Minnesota State Fair, posing with four shirtless firefighters. State Fair pro tip: You don’t want to miss the Minnesota firefighters. The post has millions of views. One of the men in the picture is my EMT, the hot one. I send it to my group chat and nobody can agree who the hot one is. I think it’s obvious.

*****************

In the fall, I suggest to T that he visit me. I haven’t seen him in well over a year, but lately we’ve been talking all the time. He hems and haws and eventually gives me a half-hearted excuse about feeling as if I’m only talking to him because I’m bored, because of my situation, and that if my life hadn’t slowed down like this I wouldn’t even look his way anymore. I can see through it, and I press him, until eventually he admits that my lack of mobility isn’t compatible with his lifestyle of spontaneity and constant travel, that we could never be together because of it. I’m gutted, angry, ashamed. Most of all, as much as I want to believe he’s wrong, to change his mind, I know there’s some truth to his words.

*****************

T was there; when I knew I was sick but everyone else was starting to suspect I might just be crazy, he had a plan for me, an investment in my recovery. Stop eating this, start eating this, everything from scratch, spring water only. You don’t have room to slack, he told me. I rolled my eyes. Deep down, though, I was grateful that someone cared enough to want to help, to not just shrug their shoulders like my doctors had been doing for months. And when my MRI report said myocardial fibrosis and right ventricular hypertrophy and I landed in the hospital, when I lied flat on an operating table with a catheter in my heart and saw the grave expressions on my doctors’ faces, when he texted me how did today go lil mama, when he called me immediately after I told him, when he looked like he might cry on my phone screen, I felt it. But there’s a limit, I’m learning, to what some people can bear.

*****************

I long for a love that is not contingent on how well my body is working, one that understands how this illness makes both spontaneity and planning ahead more difficult, that celebrates the wins and grieves the losses alongside me. In one of my pulmonary hypertension groups, a man is posting updates about his wife’s double lung transplant recovery. She’s up walking today! or Well, we had a bit of a setback. I wonder about my future, if I’ll ever need one. I wonder what it would be like to go through it alone.