Over the last year or so, Amy DeBellis has been one of my favorite newer short story writers. Now she has a new novel, ‘All Our Tomorrows,’ published by CLASH Books, which is one of my favorite books of the year.

Her writing is so skillful: the language, the plots, the pacing, the characters. But I also love her writing because I find many of her stories to be dark and bleak. To me, her stories feel steeped in depression, menace, and a kind of claustrophobic doom.

I want to present the reader some examples of stories we’ve published by DeBellis:

‘Purgatory’ –- a short story about a teen who becomes infatuated with a boy at her highschool who is killing animals. Soon he teaches her how to hunt and they start shooting animals together in the woods: deer, foxes, frogs. At one point the boy says: “Only ever point the rifle at things you are willing to destroy.” Then the story says: “She thinks of aiming it at every tree on her property, at her house, at her mother’s car. Into the open cavern of her own skull.” The story ends with them shooting the neighbor’s cat.

‘His Body’ — a short story about a woman whose husband has caught an STD that causes incurable lesions to break out all over his body. The holes in the flesh never go away, until eventually his entire body is covered in them.

We also published three micros by her:

‘Yakutsk’ — about a woman who is getting ready to wander alone into the frozen taiga

‘Wake’ — about a woman at her mother’s funeral. First sentence: “Morning: the sun smears blood across the sky.”

And a micro titled: ‘Even My Fantasies Are Chronically Ill.’

I spoke with DeBellis about her writing.

***

Chris Dankland: Hi Amy! Thanks so much for taking the time to talk to me. Do you feel like your writing as a whole tends toward the melancholic, or does it only show up in certain pieces? Is that feeling something you consciously cultivate and lean into, or does it emerge naturally?

Chris Dankland: Hi Amy! Thanks so much for taking the time to talk to me. Do you feel like your writing as a whole tends toward the melancholic, or does it only show up in certain pieces? Is that feeling something you consciously cultivate and lean into, or does it emerge naturally?

Amy DeBellis: I do think it leans towards the melancholic as a whole. (In fact, it’s like the Tower of Pisa with how much it leans…) I’m trying to think of a piece I’ve written in the last couple of years that doesn’t have that darkness, and I’m coming up short. Even humorous pieces (“Upgrade” in HAD, for example, or “Persistence” in Roi Fainéant) have elements of darkness in them—it’s just that that darkness isn’t played straight the way it is in the majority of my writing. Yeah, it’s in everything. It emerges naturally. I love beautiful things—for me, in many ways, the written word is the ultimate form of beauty—but I also believe you can’t have beauty without something to contrast it. That discordant note. That, to quote Donna Tartt, “little speck of rot”. Except for me it’s a little bit more than a speck.

CD: To me, your stories often feel physically heavy. Sometimes I get a weird image when I read your work of a stone sinking in water. You are very good at embodying emotion and describing it in a tactile way. Your stories feel like they live in the body: grief shows up as fatigue, sorrow has weight, dread feels like muscle tension. Is this a conscious part of your craft, this physical translation of emotional states?

AD: I love the image of the stone! And that’s a huge compliment, that my writing could give you this mental image. I’ve always believed that the body is the seat of memory. There’s this wonderful Stephen King quote: “Art consists of the persistence of memory.” So the body and art are inextricably linked, being as they are both holders and representations of memory. And since the present runs continuously into the past, almost everything not held by the future is already a memory.

I personally feel emotions very strongly, so no, it’s not really conscious that this comes across in my work. I mean, of course I try to choose the best descriptors for a feeling of dread, but the translation of emotional states to the physical—I believe it’s the most powerful way to get across emotion to a reader who might not have experienced the same thing that’s happening in the story. Let’s say there is a story about a grieving widow. Not everyone knows what it’s like to have lost a husband, or even to have lost a close family member, but everyone knows the feeling of grief. Describing it as a physical sensation is a way to bring the reader into their body (not their mind, where they’re thinking Oh but I was never a grieving widow) and force them to feel the emotions of the piece.

CD: I feel like the three main characters in ‘All Our Tomorrows’ are all stuck in a depressive rut at the beginning of the book. The characters are isolated in the sense that they are always wearing some sort of mask around most people. They don’t feel a real human connection with others, and this only starts to change near the end of the book when the characters meet.

For most of the book, each character seems trapped in their own depressive logic, their own sealed inner monologue. Was it challenging to bring them out of that headspace and allow for genuine human contact?

AD: It was a bit difficult, but it was also really fun. I massively enjoyed describing each character from the viewpoint of the others—it allowed me to view them from the outside looking in, for once. I am not one of those writers (no shade to them though) who says that their characters are speaking to them in their head. But for the scene where they all meet—particularly the second one where they’re all together—I kind of just let the words flow. My characters took the reins more than ever before. I truly had no idea what Janet was going to say when [redacted]*, for example. Or when Gemma figured out that [redacted]*. It was truly magical seeing their personalities come alive on the page.

*I am keeping everyone safe from spoilers.

CD: I feel that climate change is mostly unstoppable. I have little to no hope that humans will solve this problem, and I believe that things are only going to continue to get worse from here on. Humans are survivors, but I think that the Earth in which humans will have to live, 200 or 300 years from now, will be so degraded that it won’t be all that different from hell. I don’t feel hope for the future, in the long run.

The existential threat of climate change is a worry hanging over the heads of all three main characters in ‘All Our Tomorrows.’ How do you personally feel about climate change?

AD: Sadly, I agree with you. I think we’ve all seen over the past few years that even if humans could solve this problem, we wouldn’t want to. And by “we” I mean the people who run the world, the CEOs of megacorporations, the billionaires who wreak the most environmental damage. It’s my opinion that they are almost uniformly psychopathic in their behavior and their lack of empathy. No normal person would want to do the things they’ve had to do in order to gain their position—and I believe that if a normal person did find themselves with that much power, they wouldn’t remain normal for very long.

On the one hand, I truly enjoy my laptop, and my phone that allows me to contact my friends overseas. And parasite-free, running water. And medicine! But I also believe that our modern way of life is an aberration, a blip, almost a wrinkle in the way things are designed to be on earth. We are not entitled to live this way, it is not sustainable, and we are paying the price. People forget that for the overwhelming majority of human history, we lived in hunter-gatherer tribes. The Neolithic Revolution (when humans first began to farm) happened only ten thousand tears ago, which is around 3% of the time Homo sapiens have existed. And the Industrial Revolution, which gave us our industrial capitalism and modern infrastructure and nearly everything we feel entitled to as a part of “regular life,” happened so recently that only about 0.08% of human history has occurred after that. It’s mindblowing that we’ve caused so much damage to our planet in such a tiny fraction of time.

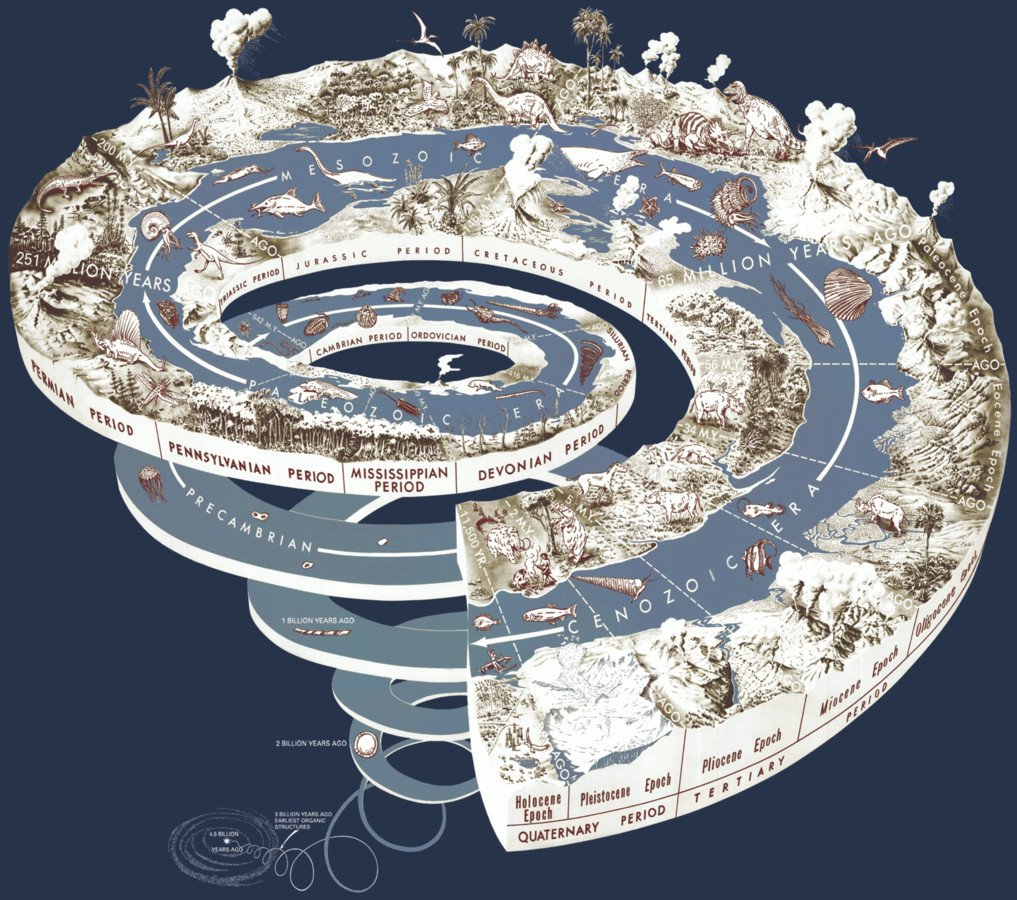

And that 0.08% is what we think of as normal. Our own lives are so short in comparison that, looking back along the eight or so generations that have lived since the Industrial Revolution, it really does seem like it’s been forever. There’s a part in All Our Tomorrows where one of the main characters is thinking about the spiral drawing that’s mean to represent all the eras on earth — something like this, but colorful.

Most of it is blue and green. Only the very newest end of the spiral is a different color. To quote my book, that’s “the Anthropocene, a slice so tiny you could easily miss it, a fingernail sliver of rust-covered gray. If you zoomed in enough you could see minuscule buildings, cars, an airplane, all hovering precariously just at the edge. To Anna it looked as though anyone standing on that edge was about to fall off into nothing, into the timeless black that surrounded the spiral.”

I fear I’ve gone into a bit of a raving tangent, but I’ll wipe the froth off my mouth, do some deep breathing, and attempt to answer your question more succinctly: I don’t feel hope for the future in the long run, either. Climate change is multi-pronged, as it gives rise not only to fires and floods but also ancient pathogens thawing out of permafrost, mosquito and tick-borne diseases moving further and further across the globe, and so many other things we simply aren’t prepared for.

CD: In a past interview, you mentioned that you were “gearing for a not-so happy ending” with ‘All Our Tomorrows’ but ultimately felt like the novel needed a more hopeful ending because you didn’t want the book to “leave readers feeling like the novel was a bunch of pointless doom—we get enough of that from social media and the news.”

Are you concerned that readers will misread the darkness in your work as nihilism? How do you feel about nihilism? What do you hope that readers are left with after reading ‘All Our Tomorrows?’

AD: I’m not really concerned that they’ll misread the darkness in my work as nihilism. If they do, I don’t mind. I would probably mind if I branded myself as some kind of “Hope Coach,” but thankfully that is not a direction I have gone in.

One of the phrases you used earlier to describe the feelings my work gave you—“claustrophobic doom”—made me smile. I love claustrophobic doom! (Writing about it, not feeling it.) But I don’t think that all of life is claustrophobic doom. Existence is multifaceted, and I choose to bring attention to the darker parts of it. They’re a lot more fun to write about, for one thing. But I also see a lot of toxic positivity everywhere. You get demonetized on social media if your content is too depressing, which admittedly makes sense from a branding point of view. But at the same time, I don’t agree with phrases like: Everything will be okay in the end, and if it’s not okay, then it’s not the end. It has its uses during a panic attack, I suppose, but on the whole that phrase never made sense to me. Like, what if someone is dying of a horrible disease? What—are you saying that things will be okay in the end because of the sweet relief of death? Well, okay, I guess that’s one way to think about it, but I don’t think that’s what that particular phrase is going for…

The most popular type of nihilism seems to be that life is meaningless and has no value, nothing you do matters, and there is no point to anything (and, I can’t help reading this into it—that you may as well just shuffle yourself off this mortal coil sooner rather than later).

Honestly, I think those nihilists are overthinking it. I don’t like to burden my small monkey brain with the overall meaning of life. Like, yeah, duh. Nobody knows the meaning of life. Maybe there is none. Where I don’t agree with nihilism is that life has no value. I happen to like being alive, for the most part. There is so much beauty to be found in life. There’s beauty in pursuing creative activities, in spending time with loved ones, in listening to your favorite music, in eating good food. I don’t care if it’s meaningless—I still enjoy it. And hey, maybe it’s all meaningless in the end, since we don’t live forever, and you and everyone you know will eventually die…but honestly, I think immortality would be so much worse. It’s the ephemerality of life that makes it so precious. (And, going back to the psychopathic billionaires, this is something that the most powerful people on the planet seem to have forgotten. I truly believe they can’t enjoy small pleasures anymore. They want to rule the world and live forever because they can no longer appreciate things that would make the dopamine and serotonin receptors in a normal, healthy brain light up.)

Towards the end of All Our Tomorrows, it was a bit of a challenge to keep the story realistic but also have it not be totally depressing. The ending of Janet’s last chapter, as well as the ending of Gemma’s last chapter (which is literally the last sentence of the book) is probably my most clear and straightforward answer to the question that snakes through the manuscript, which is essentially “What are we supposed to do about all this anxiety, all this uncertainty, all this pain?”

So, to answer your question, I want readers to come away from All Our Tomorrows with a sense of hope, with the knowledge that they can do something—even if it’s just something for themselves, and not something that saves the world, because that’s impossible—but something. Whether that’s spending time with family, or doing something creative you enjoy, or being with the person you love. Something that has meaning, and purpose, and value. And that is what makes my book incompatible with nihilism.