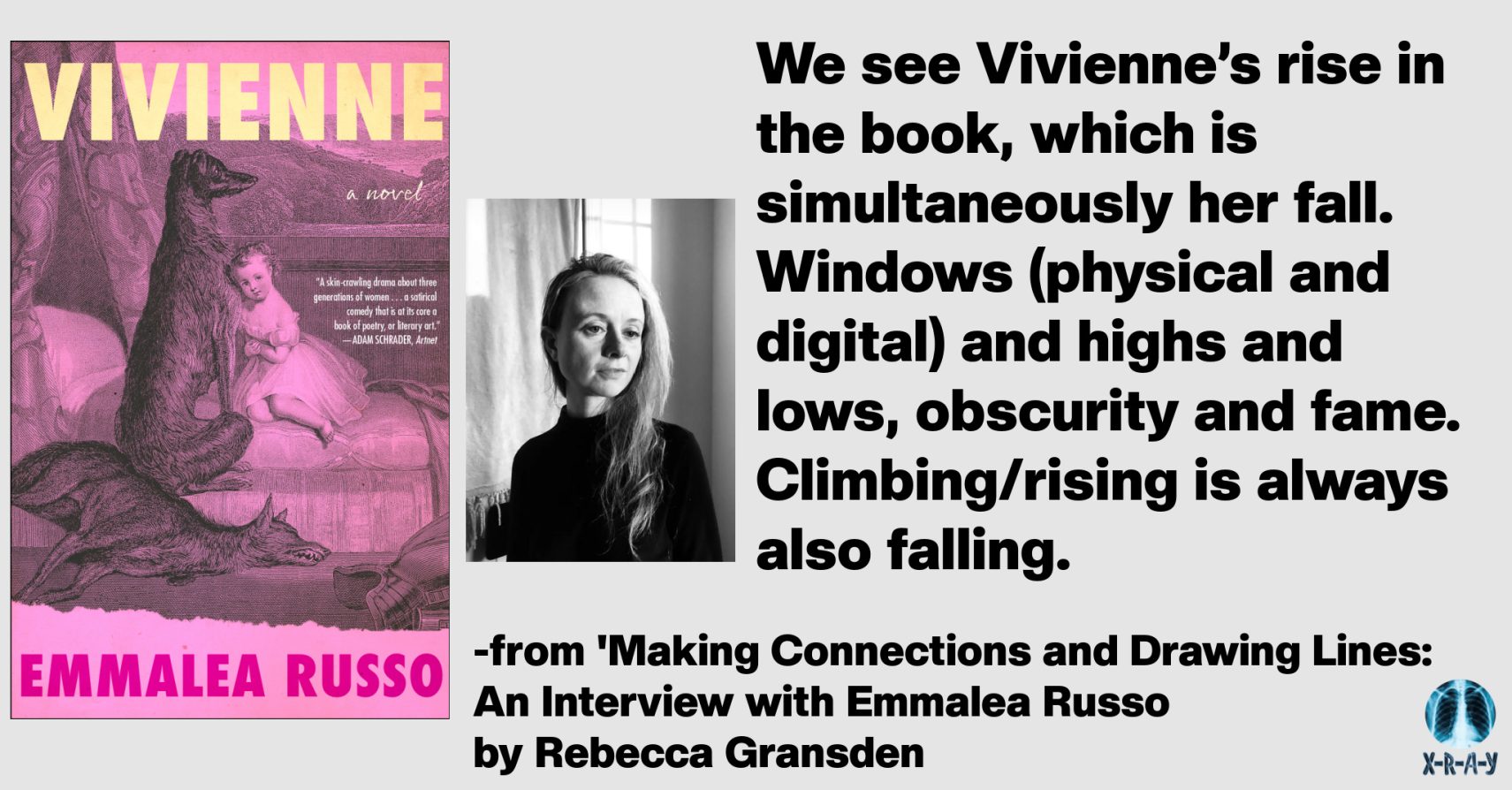

Since its release in fall 2024 Emmalea Russo’s Vivienne (Arcade Publishing) has had time to percolate with the culture it so sharply interrogates. A slanted satire, the book poetically autopsies online mores and offers a giddy sojourn to the realm of the artist, both the world they invent for themselves, and that imposed from outside. Three generations of a family are positioned as focus for the novel, and Russo bestows this trio with an enchanted ordinariness. What constitutes a violent act? By the end, flesh and blood puts words to shame. I spoke to Emmalea about the book.

Since its release in fall 2024 Emmalea Russo’s Vivienne (Arcade Publishing) has had time to percolate with the culture it so sharply interrogates. A slanted satire, the book poetically autopsies online mores and offers a giddy sojourn to the realm of the artist, both the world they invent for themselves, and that imposed from outside. Three generations of a family are positioned as focus for the novel, and Russo bestows this trio with an enchanted ordinariness. What constitutes a violent act? By the end, flesh and blood puts words to shame. I spoke to Emmalea about the book.

Rebecca Gransden: WHO IS VIVIENNE VOLKER

Central to Vivienne is the triumvirate of Vivienne herself, Velour, and Vesta. Do you recall how the characters came to you? How did you decide upon their names?

Emmalea Russo: They are certainly a triumvirate, a holy or unholy trinity of Vs. Vivienne Volker sort of tumbled out of a poem I wrote which featured Hans Bellmer. I wondered what his family legacy would be like if he had another lover—one with whom he had a child. Velour Bellmer is Vivienne and Hans’s daughter and that name came to me in a sudden rush—like, duh—of course Vivienne would name her daughter after a fabric! I’d never heard the name Velour (Vel, for short) and I sort of love it. Vesta, Velour’s daughter, had to be another V—and I was thinking of the vestal virgins, the goddesses of home and hearth who kept the fire of Rome going.

RG: I’m drawn to the attention you give to the idea of harm. In the media landscape described in the book, harm can be something seemingly arbitrarily ascribed, and amorphous in its definition. There are incidences for your characters that involve their harm, whether that be at the reputation level, or of the actual bodily harm variety. How did you set about incorporating the idea of harm into the book?

ER: Harm was such a buzzword when I was writing the book. I grew up around a lot of lawyers, specifically criminal defense attorneys—so I became interested in this idea of harm, which is undeniable but also unprovable, as it relates to the presumption of innocence, reasonable doubt, due process. In Vivienne, detractors claim her work is “harmful” or has “harmed” them in some way. What does this really mean? Is it an artist’s job to make sure their work doesn’t harm anyone? Is that even possible, or a worthwhile goal? What are we to do with our harm? Are we supposed to avoid or boycott works that are risky, problematic, or triggering? In the book, harm and victimhood get weaponized. Accusations of harm become like babyish tyrannical refrains. There are piles of interesting things hiding underneath the word “harm.”

RG: You utilize various mediums throughout the text, from comment threads to letters. I found this creates a sensation similar to that of social media scrolling, a pull into a vortex of information. Eyewitness reports on Volker turn up amid these comment threads, presenting tantalising glimpses of her. There is a hunger to construct the person from these fragments, an impulse that becomes a game. Where do you stand on the public and the private when it comes to an artist’s life, and to what extent does this influence your own approach to publicity in relation to your work?

ER: Great question. Yes, there are these quick glimpses of Viv—glimpses which make her appear even more iconic and unreachable, in a sense. The Bellmer-Volker-Furio clan is quite private. On the one hand, it’s fair game to reach into a public figure’s life—to try and grab bits and pieces and make stories. On the other hand, there’s a kind of cruelty and madness about it. These days, we do the machinery’s work for it—exploiting ourselves and our images. I often wonder about the backlash—the children of influencers, for instance. I think these publicity technologies can give way to delusion and dehumanization. For instance: we begin to believe that a person is what a person posts. Or, that we know what a person cares about because we follow them online. There’s a level of unknowability, opacity, that has to be preserved. The danger comes when we forget the difference between info and truth. When it comes to my own work, I tend to be very private about my personal life. And yet—how to foreground the work and hope people read it while keeping oneself private? It’s not a clean, clear line. Things get fuzzy and messy, inevitably. I don’t know!

RG: Velour pictures Wilma’s broken body on the ground seven or eight stories down, Max’s needled, drug-torn form stacked atop it. And her father, too—thin and filled with cancers. Her own dead body, her mother’s, her daughter’s, the dog’s . . . their clothes blowing in the wind and smelling of piss, French perfume, and shit. A saint or an angel arrives—one of these entities her mother apparently believes in—and blesses them, makes the sign of the cross, then continues on. Their bodies, piled high, block traffic. Lou picks the whole mess up in his garbage truck, compacts them until all organs get crushed.

A theme that haunts the book is that of accusation, and what it means to stand in judgement. So much of Volker’s story is surrounded with rumor and insinuation, questions of guilt and innocence. For me, a great strength of the book is its careful and nuanced exploration of human messiness. Do you view Vivienne as a moral work?

ER: This is such a brilliant question. I’m glad you thought of it as carefully exploring human messiness—which is essentially what I aimed to do. I guess Vivienne is a deeply moral work, though not in an obvious way. I certainly hope it’s not moralizing or preachy. I think there’s a big difference. I get irritated when I can feel the author of a work of fiction winking at me or letting me know she’s on the right side of history. It’s belittling and shoots me out of the world. In Vivienne, the characters are not outright judges for their transgressions, but they do transgress a lot, and they are met with consequences. Vivienne wrestles with her own conscience and guilt, as we see in the church scene, and she seems to be guilty, but likely not for what the internet crowd believes she’s guilty of. The sins of Vivienne and Velour get visited on Vesta, but in ways the characters don’t totally see. There’s a lot of fate in the book. The three Fates, like the three Vs of Vivienne, are women. Maybe the book could be read as cautioning against forgiving oneself too quickly—the potential dangers in seeing oneself as a victim and not (also) a perpetrator. The ethics of guilt and wrestling with fate are at play.

RG: Canines play an important part in the book, and a character’s recurring dream features the powerful image of a dog. What drew you to include this aspect? Have any real life animals inspired the dogs featured in Vivienne?

ER: I’m happy you asked this! Dogs are everywhere in the book, including on the cover. I grew up with dogs, and I have two of them now. The dogs in Vivienne are amalgamations of many dogs I know or have known IRL. The family dog’s name is Franz Kline. Kline was an abstract artist from Pennsylvania, so I thought it fit. But also, a friend of mine told me that she met a dog in New York once named Franz Kline, and I thought it was perfect for the Vivienne dog. I was at a dog park a few months after the book came out, and I met a dog that matched the description I gave of Franz Kline perfectly. It was uncanny. There is such an innocence, honesty, and immanence about dogs, and it’s excruciating to see an animal hurt. Animals witness our sorrows, wrongdoings, all of it—and we project onto them. In the book, they become sacrifices, keepers of dreams, companions, protectors, gods, barometers. Maybe dogs serve as a kind of counterpoint to human messiness in the book because, as Freud said, dogs bite their enemies and love their friends, “quite unlike people, who are incapable of pure love and always have to mix love and hate in their object relations.”

RG: Vivienne presents the idea of growing a simple soul. What does this mean?

ER: Lars Arden, the opportunistic and savvy gallerist who scoops up Vivienne’s work after it’s been ditched by the big museum, is also somewhat of a mystic, a seeker. And throughout, Lars is quoting and thinking of the French mystic Marguerite Porete’s 14th century text The Mirror of Simple Souls. It’s essentially a kind of guidebook for union with the divine, and also a profound and profoundly weird meditation on the nature of love and how to make one’s soul “simple” in preparation for meeting G*d. Porete was burned at the stake for her book, and for refusing to refute its contents. She was called a heretic and a pseudo-mulier (fake woman). These accusations are also levelled against Vivienne. I wanted Lars to be reading this obscure medieval spiritual text and really taking it to heart. There is a lot of dark humor and satire in Vivienne, and Lars is slippery and scheming, but he’s also wanting to better himself—to grow a simple soul. Simplifying one’s soul involves sloughing off earthly stuff. Some people think Lars is like the “villain” of the book, but I don’t see him that way. He’s caught between accruing and simplifying, between growing his reputation and growing his soul. Can you do both at the same time?

RG: Lars Arden met Clorinda Salazar, a socialite moonlighting as a stylist and internet writer, at a coffee shop a few years ago when they struck up a conversation about an article she was writing entitled “Sexualities You Didn’t Know Existed.” Clorinda’s reputation preceded her, and Lars felt she lived up to the hype: a gorgeous, big chested redhead with an encyclopedic knowledge of who and what was in. The daughter of the late abstract expressionist known simply as Salazar, a painter who won notoriety amongst the downtown set and beyond when he allegedly pushed his wife, the artist Paulina Paz, from her studio window onto the sidewalk. After she woke from a brief coma following the six-story fall, she didn’t press charges and their careers flourished.

I’d like to talk about falling. An incident of a person falling to their death hangs over the novel’s characters. It’s a concept that lingers, not only as a result of the tragedy inherent in the incident itself, but also on a deeper, symbolic level. It put me in mind of the depression era financier jumpers (although I believe that is now regarded to be mostly a myth), the supposed use of this method by government agencies to eliminate people deemed no longer of use, and, most obviously, the unbearable images of 9/11 jumpers. How did this aspect of the book come to you?

ER: We see Vivienne’s rise in the book, which is simultaneously her fall. Windows (physical and digital) and highs and lows, obscurity and fame. Climbing/rising is always also falling. I was thinking of the falls and pushes in the book (and lingering questions about who was pushed, who jumped, who fell…) as ways of thinking about fault, guilt, escape, blame. It’s a sort of running joke in the book, but also deathly serious. There’s the tragedy of Icarus, of course—who flew too close to the sun and fell into the sea after his wings melted. Unica Zurn jumped from a window to her death. Deleuze did, too. And there is Ana Mendieta, who apparently fell from a window in the 1980s.

RG: This is perhaps an example of the universe lining up in itself, but I increasingly find myself asking writers about their relationship with synchronicity and its importance with regard to their work. How do you view synchronicity, and are there any examples of it in your own creative life you’d like to share?

ER: Synchronicity! It’s incredibly important to me. Synchronicity means “same time,” and this is the principle on which divination and astrology operate. Planetary positions aren’t “causing” certain events to happen in our lives. But, there may be a correlation between what’s going on in the sky and that same moment here on Earth. Synchronicity has to do with paying attention, reading the room, making connections and drawing lines. Vivienne unfolds over the course of one supercharged week, but we see overlaps and weird connections between characters. Synchronicities between online commenters and Vivienne’s rural life. Jung thought of synchronicity as a creative act. I think of my astrology practice as the weird study of synchronicities.

RG: What does the future hold?

ER: I just asked the tarot. I got The Fool.

And also, there’s a sequel. It’s called The Moon Papers and it will be out in the summertime.