Right now we’re stuck behind a funeral procession and it looks like we’re going to be late. Mack keeps saying, How long, how long? We’re on our way to see you.

I adjust the rear-view mirror, and Mack is in the back seat, bouncing around. He never settles down when the car goes slow, refuses to be lulled like other children, does not even want to be sung to. He’s saying, How long, how long?

And it is about noon right now, and it is a beautiful day and it is November. There is a hearse way up at the front. The cars in the line are mismatched and strangely colorful. Funny how these things appear without warning. An hour ago I got the call, and I swept up Mack and yanked some clothes on him and we piled into the car and I hit the gas. I flew out of town, I don’t mind telling you, and it seemed like I turned around for a second—just one second, to yell at Mack to calm down and quit screaming—and when I turned back there was this line of traffic in front of me stopped dead. It happened so quick that I slammed on the brakes, throwing Mack and me forward to strangle on our seat belts for a second. Uh-oh, Mack said.

These long, narrow roads between towns. You know them. You always complained about them when you had to get up in the pre-dawn hours, never knew what animal would jump out from the black woods and drive you off the road into death. Every morning in winter I’d listen to you grouch as I poured the coffee, and this was before Mack was born, this was when everything between us was an adventure and the only thing that worried you was a lonely road in the dark, and my biggest fear was a spider lurking in a kitchen corner. The kitchen of that house we loved, that was a long time ago, remember? And now here we are, me here on this road and you there, and Mack is in the back seat wailing like a devil, ignoring me like he was birthed out of some other woman’s loins. Like I am not his mama at all.

Mack starts counting the cars ahead of us. They don’t make noise. I wind down my window and there’s only silence and wind. It is colder than it looks. I close the window. We’re a mile outside of town, at the part of the road where it stretches wide and flat after a steep hill, and the cornfields spread out, and at the horizon are rounded mountains so far away they look blue. An open space like this is something special around here, you remember how the first time Mack saw this part of the road and yelled Roller coaster! like it was some big deal.

Now he’s in the backseat and saying How much longer? and I tell him to keep counting cars. He skips numbers. He goes from eleven back to three.

I start counting, too. Everything is slow. And I am telling you what, these cars are all clean. I don’t see a filthy one in the bunch, not like our old beater that I haven’t taken to the carwash in who knows how long. And this day is so fine, so clear, and it’s November and just as brown and gold and blue as a late fall day can be, crisp as flint corn. On these kinds of days you and me used to go out right before dusk, we would take walks in the woods down by the old gristmill’s abandoned skeleton and I’d kiss you on a path so private no one but deer would see, and then on Sundays we’d go to your Granny’s house and eat pot-pie until we were sick.

I am on my way to see you but I am stuck. A procession is ahead of me, a long, crooked line. How long? How long? Mack is saying.

He’s lost count, and so have I. I can’t see the hearse anymore, it’s gone over the far hill and out of sight. There are three cemeteries between you and me and we’ve already passed two, and I keep hoping these cars will stop, I keep waiting for them to turn. But the cars keep moving in a slow drip-drip-drip fashion, and for some reason I am thinking of water, thinking of the word wet, thinking of sex, trying to think of the last time we did it in that small bed in our apartment before you got the night-cough and started with the pills. That apartment we had to move into after you got laid off, you hated it because you thought I hated it, but let me tell you right now: I never hated any room you were in. Right now I am thinking of your jaw clicking when you bit into a sandwich, and how the noise sounded like you were crushing gravel. The sound would satisfy me so, as if your mouth were mine.

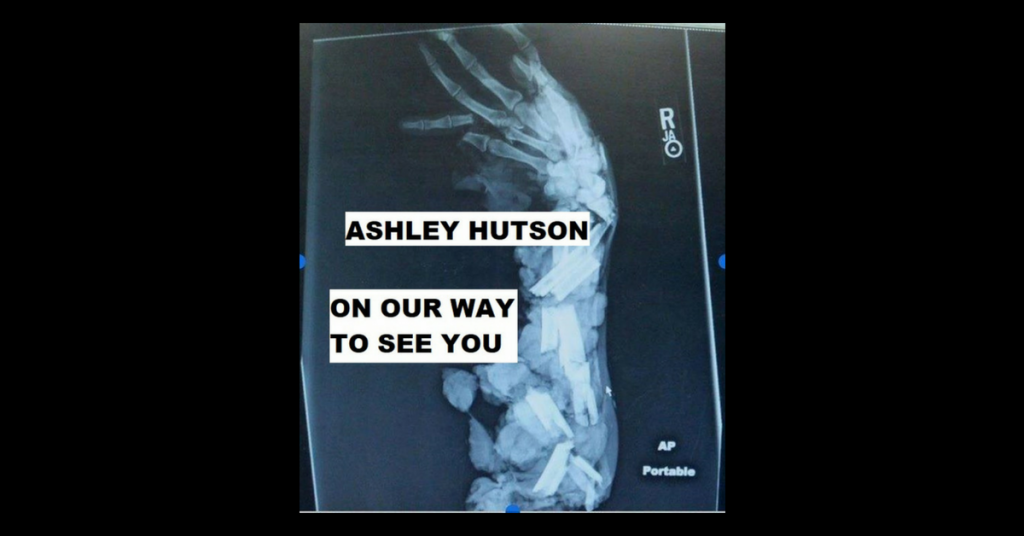

The third cemetery is approaching, and Mack is in the backseat like some kind of ghoul that was visited upon me, upon both of us, like a night flower that bloomed in my stomach, like a premonition saying How long? How long? Mack is like a lot of things but the thing I most regret is that he looks exactly like me and not like you at all, even though that was something you cooed and congratulated the baby for—you congratulated a baby—while I lay there in the hospital bed, wondering if my insides would ever feel properly arranged again. And Mack being born sickly, with my spongy bones and looking like me, surely that was some kind of punishment? An omen? But of course you took his birth as a boon, to you Mack was a gift and it didn’t matter that he was smaller than most or couldn’t get his words out clear like other kids or that maybe my blood was to blame. You said he was a good kid because he was us put together and that blood was not poison, blood was just blood, and you’d never seen an omen in your life.

We’ve been following this funeral parade for what seems like a few hours now. I am trying to get to you but there is this line of cars I cannot pass or see the end of. I still cannot see the hearse. Sometimes I get glimpses, but you know how this countryside is hilly, is rocky and rough, and I keep losing sight of the hearse over the next hill or around the narrow curves that infest this place, the steep inclines that laugh at this old car, the landscape sneering at the humans who tried to carve a road into it.

The cars passed the last cemetery miles ago and I can’t help it, I keep following them. Now they’re splitting off the main road, going up a mountain. The night is coming fast. I forgot how early darkness falls this time of year. My ears are going shut. Mack is quieter now, lying down in the backseat. He’s whimpering a little. I can’t get the memory of a normal afternoon two weeks ago out of my brain. Do you remember? It was October then. You were setting trash bags on the curb outside the apartment, and I was at the kitchen sink skinning an apple, and Mack was watching the TV in another room, and when I caught your eye through the window you gave me a smile. You raised up your hand and waved.

From the back seat I hear, How much longer? but I ignore it. I gun the engine, willing the car to climb higher, higher. Where this mountain ends, I don’t know.