On a February day in 1967, pioneering music producer and sound engineer Joe Meek shot and killed his landlady and then ended his own life. Fast forward to an episode of The Last Podcast on the Left, where Meek is spotlighted as an example of a weird life, lived weirdly. Listening to the episode is O.F. Cieri, and this introduction to Meek’s story will stir an interest that can’t be shaken. Eventually this fascination leads to Backmask, Cieri’s fictionalized account of an era defined by accelerated creative innovation, driven by obsessive personalities, and fueled by neuroses and narcotics. Applying a pulp sensibility to grand conspiracy, the novel brims with occult charm and reflects a historical moment filled with aspiration and possibility.

On a February day in 1967, pioneering music producer and sound engineer Joe Meek shot and killed his landlady and then ended his own life. Fast forward to an episode of The Last Podcast on the Left, where Meek is spotlighted as an example of a weird life, lived weirdly. Listening to the episode is O.F. Cieri, and this introduction to Meek’s story will stir an interest that can’t be shaken. Eventually this fascination leads to Backmask, Cieri’s fictionalized account of an era defined by accelerated creative innovation, driven by obsessive personalities, and fueled by neuroses and narcotics. Applying a pulp sensibility to grand conspiracy, the novel brims with occult charm and reflects a historical moment filled with aspiration and possibility.

Rebecca Gransden: A good place to start is at the end of the novel, where a note is added mentioning your first encounter with Joe Meek, courtesy of an episode of The Last Podcast on the Left. What was it about Meek’s story that hooked you? You go on to state that you felt it necessary to not dive too much further into Meek’s life after listening to the podcast’s account. Why was this, and how much of an influence is he on the novel’s own maverick music producer, Nicholas Hush?

O.F. Cieri: I definitely love maverick or cracked personalities as literary archetypes, and that combined with the unique elements of Meek’s story, like his prediction of the death of Buddy Holly or his sound recordings of a cat in a graveyard, helped form a solid image in my mind. It felt disrespectful to say a book with a cartoonish impression of a real person was related to him. I wanted to keep my version separate but still give proper credit. I made up a guy, but I still want to be honest about the material he’s made out of.

RG: Backmask is set at a time of accelerated change and excitement for the music industry, where outsider figures such as Meek, Phil Spector, and Brian Epstein could flourish and make a significant impact. What is it about this era that attracts you? When did you realize you wanted to commit to writing about it?

OFC: I don’t like it when people treat time periods like genres, and the sixties especially seem to be remembered as a brighter and more innocent time than they were. I don’t picture sunshine and flowers when I’m reading Didion, or PKD, or Vonnegut, or Kesey, or even The Electric Kool-Aid Acid Test. People in those years had anxieties on a personal and global scale just like any era, and a lot of the art of the period explored those fears. Even Spector, Meek and Epstein did it, although through the lens of their field.

I was interested in the overlap between hippies and goths. There was a big nostalgia wave for the 60s during the 90s, so a lot of hippie iconography was folded into later goth music, but obviously artists were borrowing from each other, admiring the risks earlier artists took and trying to incorporate that into later work. I’ve heard people call “The Flesh Failures” from the musical Hair the first goth song, since it’s a danceable rock number about death.

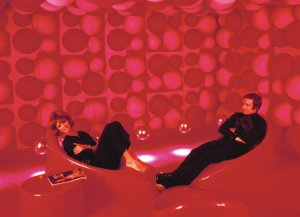

Besides that playlist I had a moodboard full of art from the sixties that isn’t associated with ‘the sixties,’ like horror comics, horror movies, the sci-fi and fantasy art of the period. I looked at modernist furniture in bright primary colors, especially Verner Panton. There was a much broader use of color in the sixties, even in the horror and drama of the period.

Besides that playlist I had a moodboard full of art from the sixties that isn’t associated with ‘the sixties,’ like horror comics, horror movies, the sci-fi and fantasy art of the period. I looked at modernist furniture in bright primary colors, especially Verner Panton. There was a much broader use of color in the sixties, even in the horror and drama of the period.

RG: For those who are unaware of the term, what is backmasking, and why did you settle on Backmask for the title of the novel?

OFC: Backmasking was a conspiracy theory that pop music albums had hidden messages that were going to brainwash kids into killing or worship Satan by recording backwards words. The most famous example is that if you play “Stairway to Heaven” backward it sounds like they’re saying “oh, sweet Satan.” The only real attempt to record a backmasked message that I know of was by the Electric Light Orchestra in their song “Fire on High,” but there’s a Wiki list of all the purposefully backmasked messages in popular music. The theory still exists, but with GarageBand on any Apple product and thousands of other music production software apps for people to play with, I think the practical issues with the theory are harder to ignore. If any SoundCloud rapper can backmask a message saying “share my music with ten friends,” why hasn’t one of them done that already? If some have, which ones? Did it work? How could you tell?

RG: Your protagonist Valerie Chill possesses an assistant position at the small audio recording outfit headed by Hush. Throughout the book she is tasked with handling many large egos and erratic temperaments. She is the anchor, although with a multitude of her own challenges. How did you go about constructing her character and what role do you view her as filling in the novel?

OFC: She’s the point of view character, and limiting that perspective was useful because whenever I felt like things were slowing down or getting too complicated I could have Valerie walk away from the scene. It was also interesting to work with the conditions of responsibility that came from her job. She’s expected to do a lot of work but take no credit. She gets locked out of rooms but expected not to take it personally. It was useful, in that I could handwave big decision scenes, but it opened up this new avenue to explore that dynamic, and what it meant for people on both sides of the door.

As for her character, I like crossdressing with literary tropes. I wanted to have a stereotypical beatnik dirtball who was also a hot girl.

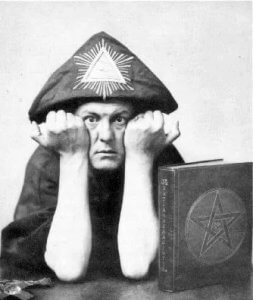

RG: In life, Joe Meek had an active enthusiasm for the supernatural and occult. Aleister Crowley enjoyed a following in certain music circles of the time and his ideas feature to a significant extent in Backmask. How did you approach the incorporation of Crowley’s concepts within the narrative? Do you have any wider opinion on Crowley you’d like to share?

OFC: It would have been funny to blame Crowley for backmasking but I couldn’t figure out a way to work him into the story. He dies before the story takes place, so he can’t show up in person. The whole motivation for the occultists is that they’re forming their own society, so there’s no point in having his organization in the story. There won’t be much conflict between the organizations since Thelemites aren’t territorial. I was initially going to have Chill do her own occult reading, but that turned into padding. Besides the characters all agreeing that they’ve heard of Crowley, he didn’t end up taking a serious role.

OFC: It would have been funny to blame Crowley for backmasking but I couldn’t figure out a way to work him into the story. He dies before the story takes place, so he can’t show up in person. The whole motivation for the occultists is that they’re forming their own society, so there’s no point in having his organization in the story. There won’t be much conflict between the organizations since Thelemites aren’t territorial. I was initially going to have Chill do her own occult reading, but that turned into padding. Besides the characters all agreeing that they’ve heard of Crowley, he didn’t end up taking a serious role.

As for what I think of Crowley, I think he’s an interesting historical figure. I disagree with some of his conclusions and I think he stole from a lot of other fin de siècle theologists, but he was literally the last surviving one in the 20th century, so he wins points for tenacity.

RG: Several conspiratorial lines converge in Backmask, most notably that of government manipulation and secret societies. Both the CIA and FBI feature, well known by now as dabbling in ethically dubious activities connected with drug trials and brainwashing. What type of research did you undertake in this area and did it turn up anything particularly surprising? How did you want to incorporate these ideas into the novel?

OFC: Podcasts are my main resource for conspiratorial research. I wanted to read the Illuminatus! trilogy but the only copies I could find were big, intimidating composite novels.

The most interesting thing I learned was in Erica Lagalisse’s Occult Features of Anarchism, where she points out that a lot of conspiratorial thinking has its roots in early pro-democracy movements of the 18th century. It explains where the connection with the Masons comes from and why so much of that symbolism lives on in classic American iconography. It’s a great book.

RG: A dominant theme is that of control. Hush seeks control over those around him, and most importantly to him, over his music, over the sound. The government agencies featured in the novel view this as an opportunity they can exploit to their own ends. An uneasy collusion results, in which each actor agrees to chase the utilization of sound for control. For the agency guys, this means the spreading of an ideology, or a certain agenda, what is referred to in the book as “remote education.” In Hush’s case the reason isn’t as clear-cut, but heavily driven by his pathologies. Music mainlines into the emotional core, bypassing much of critical thinking, making it the ideal medium for those who might want to manipulate. I’m thinking in particular of Phil Spector here, who exemplifies the extremes of this type of personality. Do you have any reflections on your representation of control in the book?

OFC: Control is an easy source for conflict and character motivation, but I think it’s because I enjoy the wish fulfillment of making up a controlling, overbearing asshole and then torturing him by making everything go wrong no matter what he does.

RG: The phenomenon of synchronicity plays a part in the novel. Many artists report the arrival of, or increase in, incidents of synchronicity when incorporating it into their work. Do you have any personal experience with synchronicity, and if so, was that connected with the book in any way?

OFC: I thought synchronicity was a really exciting challenge! I don’t know of a lot of books that try to pull it off. (If anyone knows any, please tell me about them!) It was hard, because I didn’t just want to repeat descriptions of an object for a reader to keep track of, I wanted that antsy feeling of not being able to trust yourself. It was a lot of fun!

I didn’t experience any cool synchronicities while I was writing it but I wish I had. The best piece of synchronicity I ever experienced was while I was working the register with my former work bestie. One of our customers stopped everything because she’d just gotten a text from her son-in-law that her grandbabies were born. They had a pair of twins, both girls. She showed us pictures and told us their names. They had the same names as us. She took a picture of us to show her daughter. It was very cute. No idea what it means, though. My roommate at the time said I should buy a lottery ticket.

RG: “In Chill’s limited experience with the music industry, she’d learned that being heavily armed and highly insane were more common than she’d ever realized.” Nicholas Hush is a refined twist on the archetypal cracked genius. Pioneers such as Meek, Spector and Epstein have garnered their own myths, and conspiratorial thinking surrounds their lives. Has your time writing Backmask delivered any insights into how much pathology drives creativity, and hinders it?

OFC: I don’t know. I don’t think it does. There’s a lot of steps to making something and things can interfere with or without a pathology. I do think that because people with cognitive or processing issues need to do things differently they end up more skeptical of received wisdom, and in turn less affected by criticism. Someone who doesn’t need alternatives will follow the model given to them, whereas someone who needs a different method for everything may have more practice in adapting a process without losing any essential parts.

RG: Do you have any music or artists you’d like to recommend to readers of Backmask? Are there any tracks that have used backmasking, subliminal techniques or possess hidden meanings that you’d like to highlight?

OFC: Besides the ones I mentioned earlier, the book got started by “Night of the Vampire” by the Moontrekkers, which showcases Joe Meek’s production work and is kind of what I meant by the bridge between hippies and goth. In terms of early experiments in using production equipment in music composition, including playing tapes backwards as part of the effect, Halim el-Dabh was one of the very first electronic music pioneers, and an early inspiration for Frank Zappa. His Wikipedia page is also crazy.

I made a Spotify playlist of mood music you can find here.

I made a Spotify playlist of mood music you can find here.

RG: Looking back on your time writing the book, how do you feel about it now? Are there themes featured in Backmask you feel you’d like to return to? Will you further explore this period in history in your future writing projects?

OFC: My initial concept for this project was a sort of sexy noir between Sophia and Valerie, with Chill as the hardboiled detective and Blaine as the femme fatale, but that’s not how the book turned out. The only thing I managed to salvage from the original concept was Sophie, Valerie, and the witch’s sabbath climax, but someday I’d still like to write a mystery.

Buy Backmask at Malarkey Books or Bookshop.