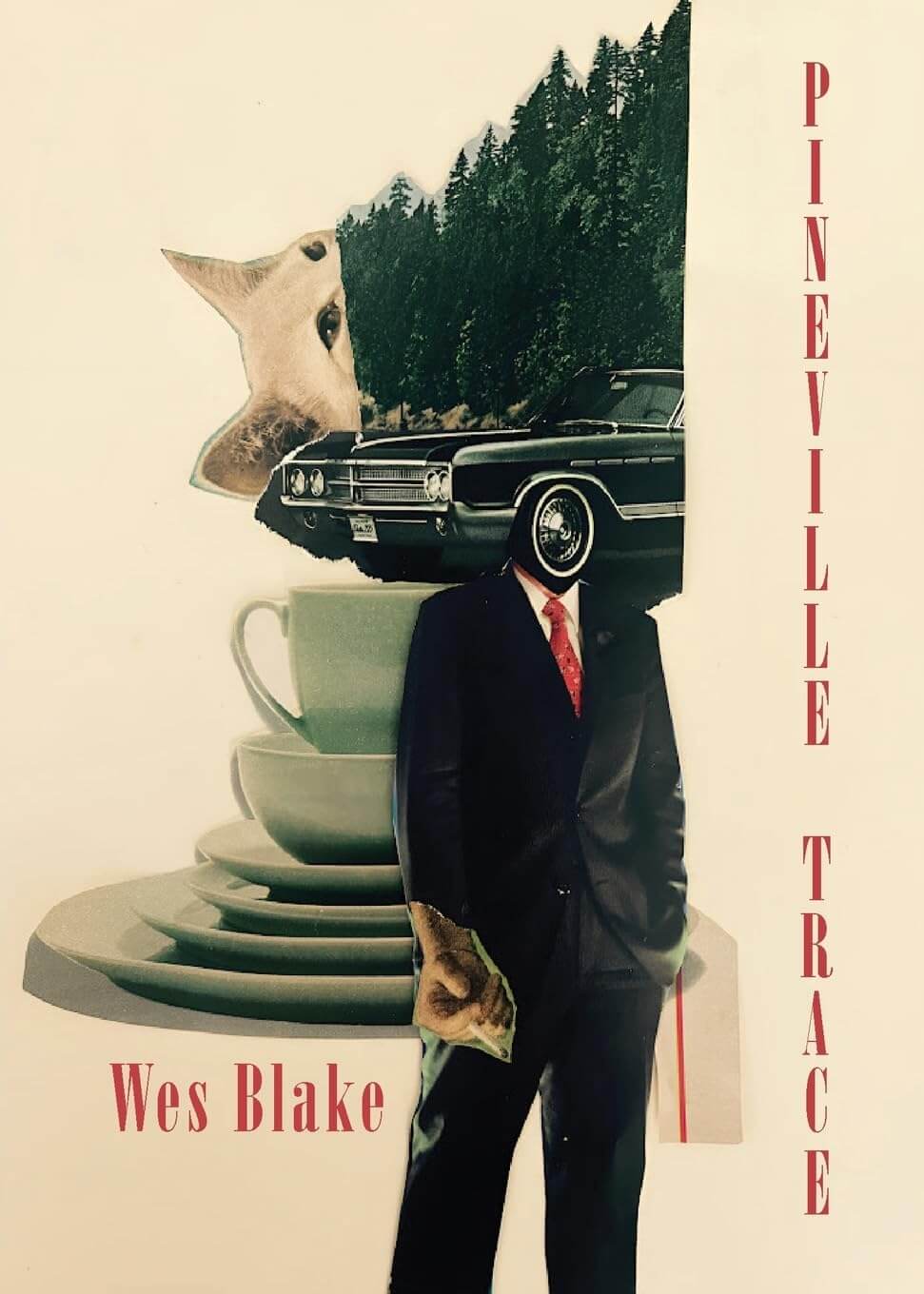

Wes Blake’s elegiac novella Pineville Trace (The University of Indianapolis’ Etchings Press, 2024) visits the wild places, those untouched stretches of land that somehow survive intact while progress lays out its encroachment in steel and concrete. In short, lyrical chapters the book travels inner and outer byways, gracefully tracking a spiritual road trip. In the pines the sun may not shine, but specters in memory shiver in broken light. I spoke to Wes about the book.

Rebecca Gransden: How did the initial idea for Pineville Trace materialize?

Rebecca Gransden: How did the initial idea for Pineville Trace materialize?

Wes Blake: The initial idea for Pineville Trace materialized in the summer of 2014 when I was just beginning my MFA at the Bluegrass Writers Studio and was in Lisbon, Portugal for the Disquiet International Literary Program. One of the speakers said to “write about what obsesses you”. And that struck me. I walked along the cobblestone streets of the Barrio Alto neighborhood thinking about what did obsess me. I remembered stories I’d heard about my friend’s great-uncle—a southern revival preacher who started out traveling with an old circus tent from town to town. And hearing firsthand stories from people that knew him about how genuine he could be, how much he impacted the people that knew him, how charismatic he could be, and how fondly they remembered him, stuck with me. There were also allegations of fraud. My idea for the character of Frank Russet was inspired by this type of character. I wanted to write about a character like that, whose real self was a mystery, to find out who they really are. So, over the next three years, I wrote a novel named Antenna about Frank Russet and how he built his life and made a name for himself. I wrote the book to find out who he really was. And I thought his story was done.

But in February 2022, I was in Pineville, KY and realized that Frank’s story was not finished. I drove by the city of Pineville and was struck by it: a small town whose quaint houses wound and coiled up along the side of the mountain in an unreal way that looked right out of a dream. I’d never seen another place like it. Then, after seeing a sign for Bell County Forestry Camp—the minimum-security prison I’d researched and written about where Frank Russet had been sentenced for fraud—I found myself following the signs towards it. The signs led me up Pine Mountain. It’s a striking place with so many pine trees that it looks more like the Pacific Northwest than Kentucky. As I approached the minimum-security prison, a car passed by on the other side of the road. It was an old late fifties/early sixties model Buick LeSabre—the same car that Frank Russet drove. It was eerie seeing such a rare car in such an isolated place. In the first novel, Frank had briefly befriended a stray cat that visited the prison. It was only a passing scene. But that would be the beginning of Pineville Trace.

RG: Who is Frank Russet, the main focus of the book, to you?

WB: I’ve been writing about Frank Russet, off and on, for the last ten years. He started off as a mystery, and in some ways, he remains one. How much of his intention was pure and how much was ambition? Did he start off with good intentions and lose his way? Did he have some measure of real healing power or was it all an act? Frank Russet is torn between the world of the body and the world of the spirit. Like all of us, there are parts of him that are authentic and parts of him that he puts on like a mask in order to make his way in the world. Only, because of his line of work as a revival preacher, this conflict is more dramatic. He’s capable of soaring highs and crushing lows. A person going up on the mountain to find the truth is an old story. For Frank Russet, who he becomes on the mountain reveals who he really is. And who he becomes when he comes down from the mountain, back down into the world, also reveals who he is. I’ve been writing and thinking about Frank Russet for so long that he feels like a real person to me. He feels like a friend.

RG: When driving east, before reaching Bell County Forestry Camp, you pass Pineville. The name of the town was what led me to the place. Both in fiction and in real life. I had imagined the house from the first sentence. And I wanted to find a house like it in the real world. I felt it must exist.

Place is an essential component of the novella. How do you use invention when it comes to location? What is Frank’s relationship to the environments he travels through?

WB: I read this article on Leonardo da Vinci a few years ago that was illuminating. Essentially, da Vinci believed that observation plus imagination equals creativity. You can see how he put this into action with both his “Studies of Water” (astute observation) and his sketches of angels and demons (pure imagination). Both da Vinci’s observation and imagination are so precise, committed, and detailed. So realistic. This combination of observation and imagination is true for how I use invention when it comes to location. I strive to closely observe places and get a sense of their tone. How does a place make you feel? And what aspects of the place make you feel that way and why? We can’t separate ourselves from our environments, and they affect our outer and inner worlds. Our inner landscapes color how we perceive our outer world. I strive to capture this reality in Pineville Trace. Frank is particularly sensitive to environment. He’s more in tune than most people are with how time affects place and how environment is both a mirror and a prophecy for self.

RG: Nature and the wild is an important aspect of the book, but central above all imagery is that of the pine trees themselves. A constant presence, whether it be close by or on the periphery, these trees frame the landscape of the novella. How do you view the pines of Pineville Trace?

WB: I followed the credo of Donald Barthelme’s essay “Not Knowing” when writing Pineville Trace. I let my subconscious lead the way. I allowed my intuition and what I had previously written lay the groundwork for what came next. And when I read the book over and again when polishing/editing I realized that many of my obsessions wound up in the book. Leonardo da Vinci was obsessed with water. I’ve always been obsessed with pines. I’m not sure why. I was close with my grandmother—my mom’s mom who we called Nanny—and, growing up, I would often stay at her house in Mt. Sterling, Kentucky. We even lived with her for six months between our move from Rowan County in eastern Kentucky to Lexington. There was a row of pine trees at the back of Nanny’s yard, and as a kid I was always drawn to these pines. Their dark green color, their coolness in summer, their smell, the way they hid you from the world. They made me feel relaxed and safe. I spent a lot of time around those pines when I was young, and I still spend a lot of time around pines. My wife and I have planted thirty-two pines on our rural property in Woodford County, Kentucky. I’m researching mystics, psychics, and energy healers for my new book, and I just read about how someone who can see auras described how all living things have an aura, but trees, in particular, have a large aura—sometimes two feet wide or more—that she can see from far distances. I wonder how she would describe the aura of pines?

WB: I followed the credo of Donald Barthelme’s essay “Not Knowing” when writing Pineville Trace. I let my subconscious lead the way. I allowed my intuition and what I had previously written lay the groundwork for what came next. And when I read the book over and again when polishing/editing I realized that many of my obsessions wound up in the book. Leonardo da Vinci was obsessed with water. I’ve always been obsessed with pines. I’m not sure why. I was close with my grandmother—my mom’s mom who we called Nanny—and, growing up, I would often stay at her house in Mt. Sterling, Kentucky. We even lived with her for six months between our move from Rowan County in eastern Kentucky to Lexington. There was a row of pine trees at the back of Nanny’s yard, and as a kid I was always drawn to these pines. Their dark green color, their coolness in summer, their smell, the way they hid you from the world. They made me feel relaxed and safe. I spent a lot of time around those pines when I was young, and I still spend a lot of time around pines. My wife and I have planted thirty-two pines on our rural property in Woodford County, Kentucky. I’m researching mystics, psychics, and energy healers for my new book, and I just read about how someone who can see auras described how all living things have an aura, but trees, in particular, have a large aura—sometimes two feet wide or more—that she can see from far distances. I wonder how she would describe the aura of pines?

Frank is haunted by pines and drawn to them. They represent a stubborn resistance to change, refusing to lose their needles while other trees shed their leaves when the seasons change. When the wind blows, a pine’s stillness and quiet contrasts with the sound of other trees whose rustling leaves make louder sounds. Frank seems drawn to the pines in Pineville Trace for reasons he doesn’t fully understand. Their dark green and stoic stance may remind him of the peaceful reality he seeks that has always eluded him.

RG: “We’re all gravediggers.”

Frank describes, and acts out, a deep emptiness. As his travels progress, this only becomes more pronounced, as echoes of the past catch up to him, however adept he is at staying in motion. The book carries a tension, where it is unclear in which way Frank is pulled; away from the hauntings of his past or towards a daydream of a future. How do you see Frank’s path?

WB: Frank has spent a lot of his life as a southern revival preacher charged with providing salvation and healing for many people. His job was to assuage people of their emptiness, to show them the magic of life and its larger meaning and purpose. To revive them. To bring them back to life. And this seems to have taken a toll on him over time. He sought distractions and ways to escape his own feeling of emptiness that remained, and his human flaws only made him feel more empty and false. In his past, Frank spent most of his life moving. Constantly traveling from one town to the next. In Pineville Trace, for the first time, Frank must finally stop moving and face the emptiness in himself that he’s been running from. He must face the guilt over his flawed nature. He gets rid of the shackles of who he needed to be in the past, and all the weight of falling short of that. Anything short of moral perfection and performing miracles would be a failure in his former life. And he happens to be quite a flawed human being.

Escaping from a minimum-security prison—in the way that Frank Russet does and in the circumstances that he does—is an existential act. He walks away because he doesn’t want to be the person he had been before. This escape allows him to have a chance at a future with real peace, but it is not an easy escape. His past, his emptiness, his guilt over all the harm he’s caused, plague him. They are deeply carved into his nature. I see Frank Russet’s path as a perilous one because while he is striving to free himself from his past and who he’s been, the ghosts that have always haunted him do not want to release him.

RG: A key presence in the book is that of a cat named Buffalo. Animal companions often come to us when most needed, or are associated with a particular time of life. Have there been significant animal bonds in your own history, and, if so, did that feed into Pineville Trace? How do you view the connection between Frank and Buffalo?

WB: I’ve always been obsessed with cats. When I was a little kid, I wanted a cat more than anything else. As a small child, I had both a teddy bear and a small Pound Puppy kitten that I slept with. My brother and I always tried to earn the affection of Nanny’s and my aunt Charlotte’s cats. But they were slow to trust us because we were kids chasing them around without much understanding or gentleness. I remember when I was about six, another cat of Nanny’s—a white Persian kitten named Tinker—warmed to me and would jump up in the bed to see me and attack my watch band. It was one of my greatest achievements in life up to that point. My brother wound up being allergic to cats, so we couldn’t get one of our own, but many years later, as an adult, my wife and I have had several cats. We have a calico cat named Pig, and she’s been my nearly constant companion for the last seventeen years. She sleeps in the crook of my left arm most every night, after trying to bite my nose several times. Her Christian name is Lilly, but her personality earned her the name Pig. When I was a little kid, we had a Cairn Terrier named Daisy that I was close with. I had read too many Jack London books, so I tried to have her pull me around on my skateboard while holding her leash like she was a sled-dog and imagining we were in the Klondike. This obviously wasn’t a smart idea, especially on hills. Animals are completely loyal when they choose you. They really do offer unconditional love and friendship in ways that humans often fall short of. All they want is your time and attention, which is such a pure intention. There is something mysterious about cats, and they must be won over. But once you earn their trust, they are reliable.

Buffalo is a guide for Frank, and she is a true friend. She is there for him, accepts him for who he is, and Frank doesn’t have to be anything special for her. He only has to be himself. For a lot of his life, he’s been expected to perform miracles, heal people, and live a perfectly moral life. No human being could meet these standards. So, Buffalo, is such a welcome presence for Frank. She has no expectations for him, and she reminds him of the simpleness of life and what really matters. And, in return, Frank is a loyal and dedicated friend to Buffalo.

RG: You display the natural elements and the seasons as signifying incremental change, a signpost to an unknown future or destination. I took this to be in strong parallel to Frank’s inner movement, not only his compulsion to keep running, but also his wider struggles. There is a blurring of lines between the exterior and interior that gives the book a dreamlike quality. In terms of character development, what was your approach to Frank and his relationship to the passing of time?

WB: The seasons are a reminder for Frank of nature and time’s passing. The seasons remind him of reality and connect him to the nature of time, change, and impermanence. He’s been disconnected from nature, following his own ambition—and the expectations that accompany that—for most of his life, and connecting with the concrete reality of impermanence and change that the seasons reveal can sometimes be terrifying. Like Washington Irving’s Rip Van Winkle, Frank Russet has awoken from a dream of his own ambition, his own movement, and his own escape.

RG: Signs, exits, fields, forests passed. The sun stayed behind clouds. Kentucky became Ohio. The light became gentler. Then headlights. Ohio became Michigan. Frank kept his speed right at the limit.

Frank’s actions at first seem illogical and as if he’s possessed by a waking dream. As the story unfolds it slowly surfaces that his chosen path is one that makes emotional sense. His travels take him to liminal environments, where he exists as someone passing through. How does the wider concept of agency and Frank’s relationship with personal autonomy come into play in the book?

WB: When Frank walks away from the minimum-security prison on Pine Mountain in eastern Kentucky, he claims his own personal autonomy for the first time. As many people do, Frank has become trapped in the role he’s created for himself. His role just happened to be that of a revival preacher. This role was necessary for him to make a living and place for himself in the world. We all take on these roles and as we age, we may find that the roles don’t align with our true nature, and the nature of Frank’s role as God’s messenger carries more weight than most. So, his experience dramatizes something that many people go through. As an old man in his last days, Leo Tolstoy had a similar epiphany as Frank when he left his home and family. Tolstoy’s letter to his wife explained his decision in words that would ring true for Frank: “I feel that I must retire from the trouble of life. . . I want to recover from the trouble of the world. It is necessary for my soul and my body.” In Pineville Trace Frank, too, is taking control of his life and throwing off the chains of what people expect of him because it is necessary for his soul. Like Tolstoy, he takes control of his life to “recover from the trouble of the world.” Ironically, the trouble of the world from which Frank must recover was also largely created by himself.

RG: Frank’s past involvement with organized religion adds extra dimension to the spiritual aspect of his travels. Do you regard Frank’s story as a pilgrimage? What do you view as the role of religion and spirituality in the book?

WB: I do feel that Frank’s story is a pilgrimage. He seeks a sacred place, a vision—a dream cabin surrounded by pines—that at first, he only imagines in his mind. Frank wants to experience the reality of the life of the spirit. He wants to break down the false separation between things. As a healer, Frank was always drawn to the raw and true spiritual elements that are often, sadly, on the fringes of organized religion. And in Pineville Trace, he abandons religion entirely to understand and directly experience the spiritual world. Scott Laughlin, writer and co-founder of Disquiet International, talks about how his friend, the poet, Alberto de Lacerda would often say, “This is what I live for: friendship and the things of the spirit.” These are the things that Frank Russet has always wanted to live for, but his obligations from society and organized religion got in the way. Frank’s biblical ancestor would be David. King David, sometimes referred to as God’s favorite, also lived for friendship and the things of the spirit. His close friendship with Jonathan shaped his identity. He was a poet and a musician. As a child, he was a shepherd and felt a close kinship with animals and nature. He was a deeply flawed human being that valued connection, lust, and love, as his relationship with Bathsheba shows. Religious stories are often parables that illustrate spiritual truth. In Pineville Trace, Frank wants to throw off the organized religious framework entirely and experience spiritual truth directly. His journey is as much an inner spiritual journey as it is a physical one. As Frank proceeds on his journey, the illusion of separation between the physical and spiritual world disappears.

RG:. He had to look tough. Serious. He considered his khakis, boots, flannel. He wished he had his old suit: pressed black slacks, black suit coat, fine black silk socks, polished black shoes, a bright, starched white button-up shirt, and his silk black tie. In that suit he could convince anyone of anything. Even himself. At least he used to be able to.

Clothing is a recurring theme throughout the book. From Frank’s orange prison jumpsuit to later changes of attire, the clothes are more than something to wear but take on the quality of costume, sending out a specific signal or impression. What do these costume changes mean to Frank, and what, if any, significance do they have on a narrative level?

WB: In Frank’s previous life as a southern revival preacher, appearances were important. His smart black suit and appearance helped sway his audience into belief. For him, clothes represent both identity and a mask. When he trades out his suit for an orange jumpsuit, he’s made even more aware of the shallowness and unreality of identity and how we present ourselves to the world. But he still struggles to separate himself from his ego. He still longs for the past and that suit represents his peak in life. Even as he struggles to move beyond his ambition and ego, they still hold sway over him. Macbeth’s identity is also represented outwardly by his change from a soldier’s costume to that of a king’s robes. After Macbeth has murdered the former king to secure his place as king, Angus says that Macbeth must feel his “title hang loosely about him, like a giant’s robe upon a dwarfish thief.” Clothing does represent our identity to the outer world, and Frank, like Macbeth, must feel ill at ease in some of the costumes he’s presented to the world. At one point in the book, Frank finds a secondhand suit, a tattered approximation of his former costume. It is a fair representation of his inner state in that moment.

RG: Pineville Trace is rich with symbolism. Buffalo shares her name with animals associated with great meaning, the buffalo a ghostly presence in a landscape in which they were once abundant. Later in the book the myth of Spirit Rock is recounted, and water seems to represent psychic as well as physical boundaries to be crossed. Do you regard Frank’s story as in the tradition of the mystic quest? Why does he feel the pull to the outskirts and the fringes?

WB: I do see Frank’s story as a mystic quest. Frank is seeking spiritual realities and truths and wants to shatter the illusory barrier between the physical and spiritual world. He’s always been connected to healing and that is what led him to his role in organized religion more than anything else. I’m fascinated by Native American literature and have been influenced by several books over recent years. A book called Black Elk Speaks tells the story of the Oglala Lakota visionary and healer Nicholas Black Elk and how he struggles to manifest his vision in the physical world to help warn, guide, and protect his people from harm. Ceremony by Leslie Marmon Silko is another fascinating book that haunted me and tells a story of real healing. Larry Brown wrote a concise biography that I loved about a more famous Sioux warrior and visionary Native American mystic, the son of a medicine man, called Crazy Horse: A Life. Crazy Horse was an enigma, and his own family didn’t even understand him. The book describes how Crazy Horse went off in the wilderness alone on his vision quest—a rite of passage for the Lakota called a Hanbleceya (translated as “to pray for a spiritual experience”). It seems that people who seek deeper truths, or have a capacity to sense them, often are pulled to the outskirts and fringes. Even though Frank has lived much of his life in the spotlight, he’s always felt like an outsider and feels most comfortable on the fringes. He stood in the spotlight for years because he felt he must do it to survive. And I feel that he did have a real desire to help people. But that life became hollow, and he felt the need to explore deeper spiritual truths and escape from the expectations of society. On the fringes, he feels free. He feels a kinship with ghostly presences, birds, cats, trees, and wild, forgotten things. For thousands of years the buffalo crossed the Cumberland Gap and humans just followed in their steps, and Frank feels it is a great injustice that they have been largely forgotten. On the fringes, the buffalo are remembered always, and Frank feels most comfortable there.

RG: Communication is a theme you return to. Frank’s previous life involved radio, and many of Frank’s concerns involve the signals he sends and receives. Memories appear as if broadcast from a past he is disconnected from but unable to avoid. Figures manifest as ghostly reruns in memory. What was your approach to memory for Pineville Trace?

WB: Like Kurt Vonnegut’s Billy Pilgrim, Frank Russet seems unstuck in time. When we think of the reality of time, it seems like it is always linear: past, present, and future. But when you think of how our minds experience time, it is not separate at all. We have thoughts of the past and reactions to them like judgment, desire, sadness, guilt, or joy; observations of the present and the way we feel and think about those observations; and plans, hopes, and fears of the future—along with all the emotions and judgments that come with them. And all of this is happening in the present moment in our minds. All the time. Fiction can illuminate the inner experience more fully than any other medium, and I wanted to explore that reality of the experience of time and how memories function in Frank Russet. I wanted the past and memory to be just as real as the present because that is how our minds often perceive memories. We don’t choose our memories. Our memories choose us. Marcel Proust’s narrator of In Remembrance of Things Past dips a cookie into some tea, takes a bite, and he is transported into the past as his memories overcome him. And that is how we experience memory. I wanted to capture that reality.

RG: Do you think about how a reader of Pineville Trace might react to it?

WB: Some of the books, stories, and poems that have most impacted me, like Flannery O’ Connor’s Wiseblood, Leonard Gardner’s Fat City, Denis Johnson’s Angels, Christopher Chambers’ Delta 88, Ezra Pound’s translation of Li Po’s “Exile’s Letter,” Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations, Barry Hannah’s Ray, Rilke’s “Archaic Torso of Apollo”, James Still’s River of Earth, Phillip Roth’s The Dying Animal, Richard Brautigan’s An Unfortunate Woman, Herman Hesse’s Steppenwolf, Marguerite Duras’ The Lover, Saul Bellow’s Humboldt’s Gift, James Baker Hall’s Mother on the Other Side of the World, and Franz Kafka’s “The Hunger Artist” haunted me long after I read them, for mysterious reasons. They made me recognize and remember important experiences from my own inner and emotional life. The recognition was palpable. They made me feel something. They stayed with me. My goal is for readers to have that kind of experience and reaction with Pineville Trace.

RG:. After I drive past the woman smoking in the Range Rover, at the edge of the forestry camp on Pine Mountain, I think about Frank. Think about his life. And his story. About what it adds up to. What it’s about. I say into the recorder: “I always tell the same story. Over and over. It’s the story about getting what you want. And the story about not getting what you want. It’s the only story I know.”

In reflection, did Pineville Trace give you what you want?

WB: From the conception of the idea for Pineville Trace, through its first draft, multiple drafts of polishing, and final edits, I’ve had a sense of excitement. The experience of creation was charged. The challenge of marrying this weird story to this odd novella-in-flash form was riveting. I loved being able to spend the time with Buffalo and Frank Russet. I got to learn more about who Frank Russet really is. And, even now, it’s exciting for me to introduce Buffalo and Frank to readers. If even one reader experiences a deep recognition of their own inner experience or is haunted by Frank and Buffalo’s journey, then Pineville Trace has given me what I want.