The woman who wrote Beowulf considered it juvenilia. She composed it during the years she roamed close to the old hall, hearing the revelry, watching the fighting and fucking from the slippery dark outside. Over the long seasons she recognised, in her observations of the hall, a will that sprung from its inhabitants; a mode of life that ran in tight, obsolete cycles. Drink spilled, offence taken, necks opened, blood added to mud, children made, killed. These dances played out, accumulated nothing.

Over time, she moved away from the hall and disavowed the tales she wrote about it. In their place, she composed stories that were not about human things. Wine and swords melted into the grey candlelight of the old world. She took what the land told her and made its rough clay into her letters. The humans and their fires were things she had stepped upon to light the way; this new language was in the stones, in the correspondence between root and soil, between a bird’s foot and the branch on which it balanced.

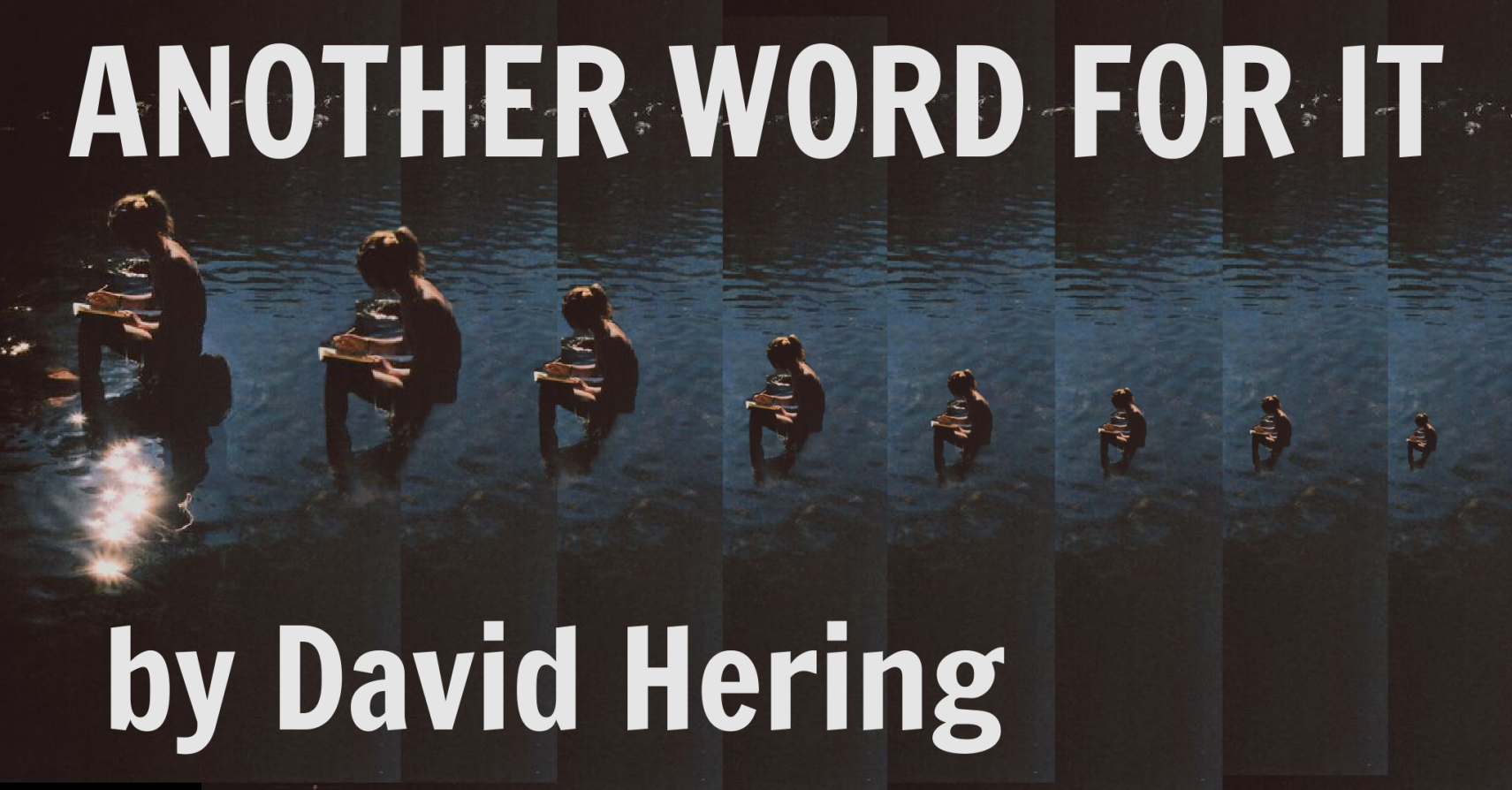

The years turned. She roamed further into the land’s interior. Caves contained dialogues of water and stone. Animals in mating bred glyphs and signs. Trees bent horselike to meet her, brushing flowers into her neck as she went. There was no longer a distinction between herself and where she placed her body. Blood from a wound was shared with whatever thorn had cut it. As water ran over her hand it carried some unseen fraction downstream. These were inscriptions the world would not preserve; a language inscrutable by the evening of the day on which it was composed. She would scratch on bark or carve into rock, then find it gone. The idea of lines on a scroll became laughable to her, pulp, dirt. The description of a blade, a creature, a warrior, a mother––this was child’s work. She found within this new expression a tapering line, a promise that vanished like ice. Foot became tree became fur became blood became water. Eventually, she was no longer visible. The hall raged on out of sight, a red pinprick, prevailing.

***

It’s a mistake for one to assume that writing is the end of anything. Anyone can knock stones together, that’s writing. Anyone can stick a sword through an eye, that’s writing. As words get older, they become solid. Eventually they’re just something to trip over, look back on, and curse at. The world does not have need of anything so final. A place is found in its accumulation and then its dispersal. What else is there to say, other than I am something that briefly came true.

Aeons pass. A body sits at a table. It is hard to make out what it’s doing through the haze––perhaps the old perpetual scratching of lines. Some monster shambles to the door, knocks, enters.