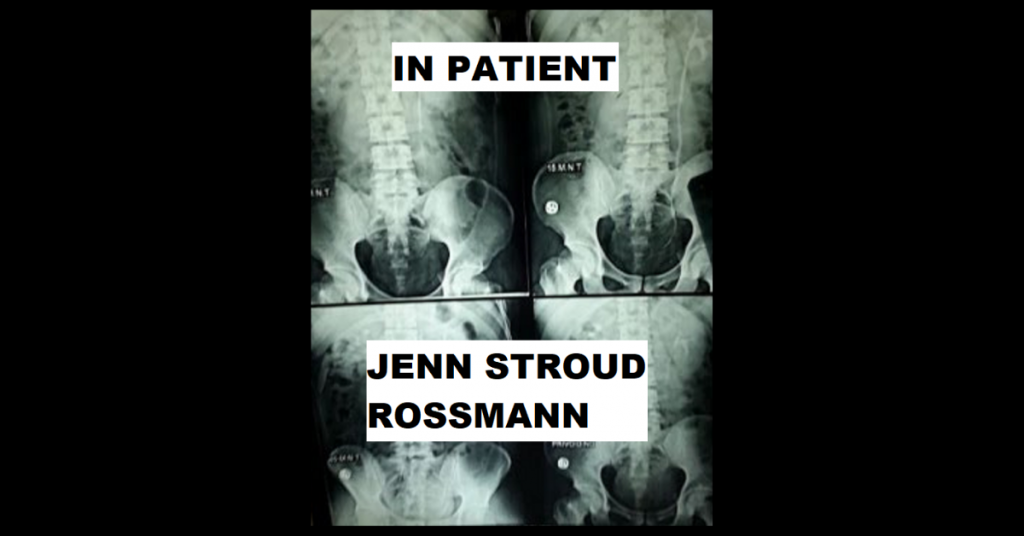

IN PATIENT by Jenn Stroud Rossmann

When the IV pump pings to warn of an occlusion, she no longer waits for someone in scrubs to respond; she unkinks the tubing herself. In the hierarchy of beeps the IV occlusion alert is low, outranked by the chirping pulse-Ox monitor and the angry squawk of the bedside fall detection mat. King EKG checkmates them all. He dislikes her charts and schedules, cringes when she calls the nurses by name and remembers their children and hobbies. Order is a dangerous illusion. He imagines himself on a science fair poster, her little bean sprout in a milk carton. He is…