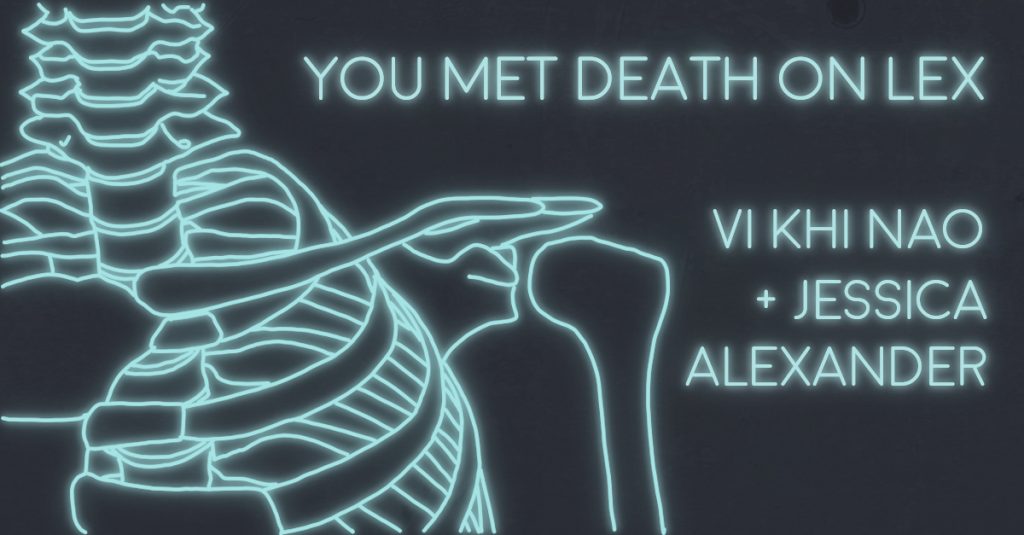

YOU MET DEATH ON LEX by Vi Khi Nao + Jessica Alexander

and asked her to meet you at a hotel in Brooklyn You would not meet her in Vegas where the sounds of your mother’s movements came through the walls between your rooms Meanwhile, in another state Death courted our brothers on Uber and Grinder As you removed one blind eye from the invisible pocket of your black bra You realized that your memory of your brother had an invisible purse With its zipper sewn on its side and its contents were pennies or wishes So when they hit the surface of your eye the world you knew rippled Back then…