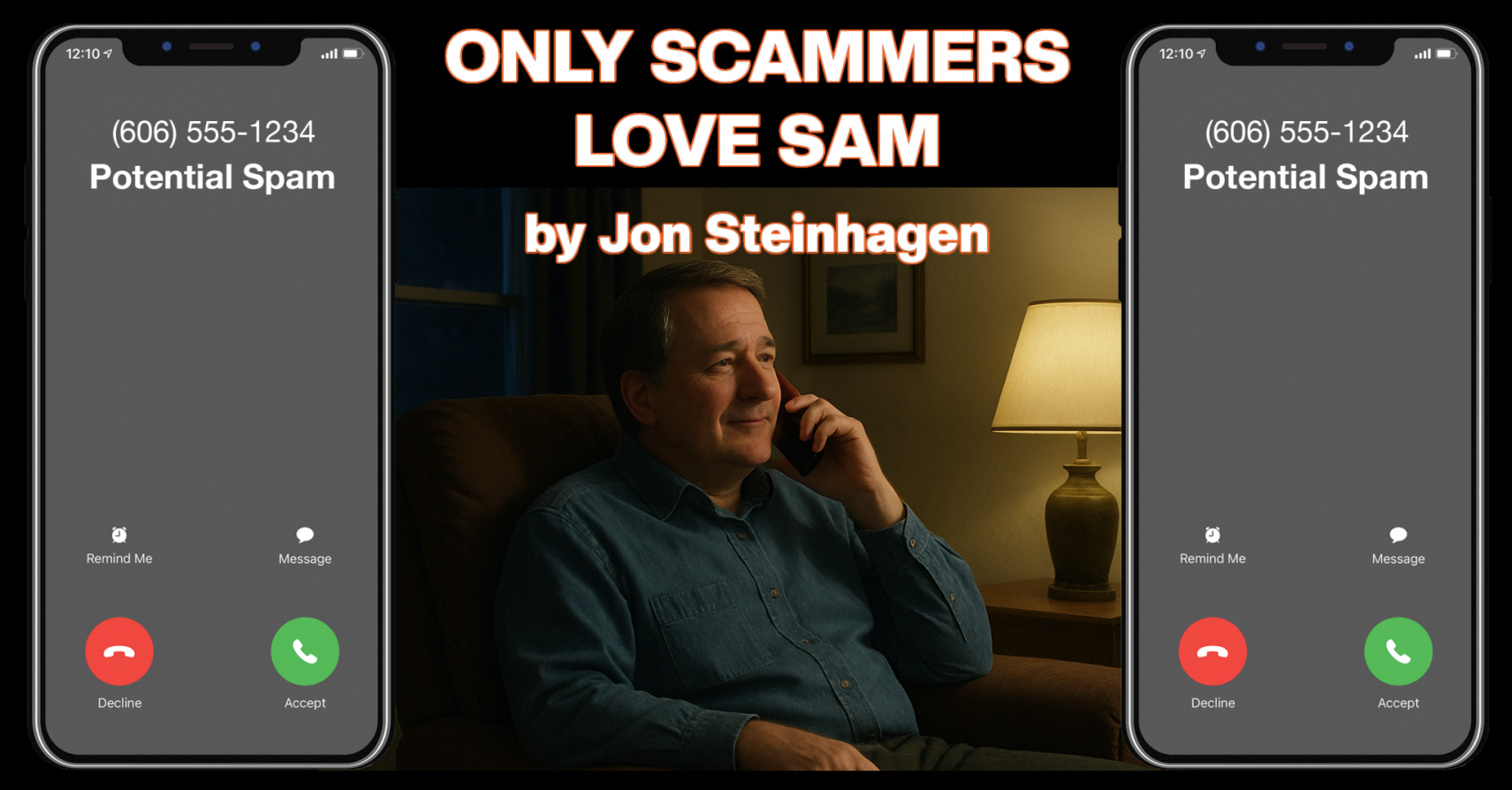

ONLY THE SCAMMERS LOVE SAM by Jon Steinhagen

“That’s wonderful, Sam,” the voice says, cooing. “May I call you Sam?” The voice is low, mellow, musical. The English it speaks is careful, cultured, unhurried, seductive (or so Sam thinks; he’s become a connoisseur over the years). Its tone is polite and comforting with just an edge of anticipation. Normally, this voice has rarely been given the freedom to speak so much, to reel off so many carefully-edited chunks of information. It senses an ultimate victory. “Sam, or Sammy,” Sam says. “That’s wonderful, Sam,” the voice repeats. “Now, all you have to do—” “My mother used to call me…