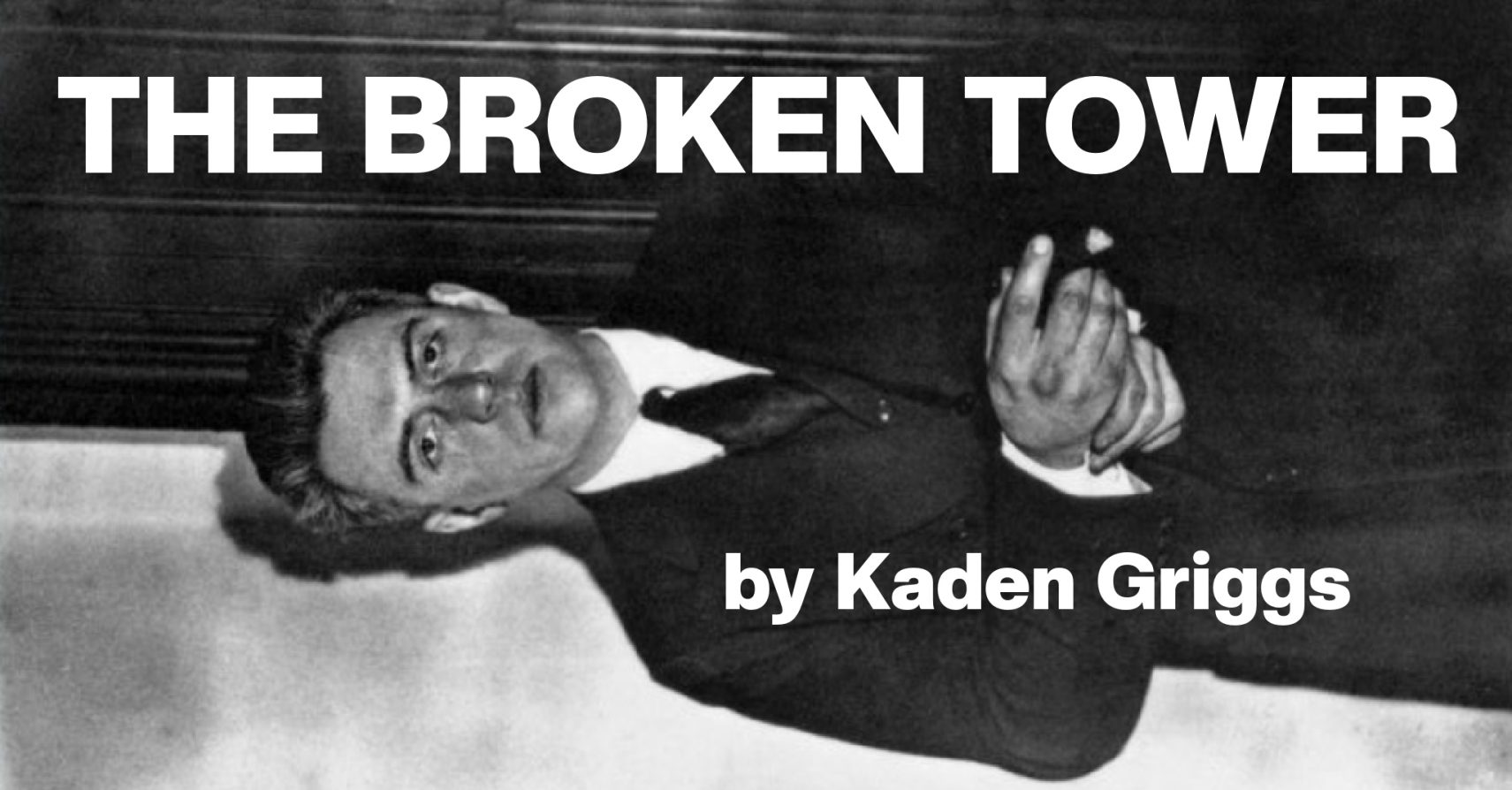

THE BROKEN TOWER by Kaden Griggs

The hulk of the Orizaba lulled hugely in the calm spring water as if the waves were tongues tasting the air in broad gulps like old hounds lapping water from ground puddles. Not much moved. The poet was drinking and avoiding his beloved. His father had died and he was very sad tonight. He had never felt emptier within. Lust enters when the hollowness leaves nothing else behind. He makes the mistake of believing again that the drinking will bury the lust and set things aright but it only invigorates the lust. Lust for all things. Lust for the remembrance…