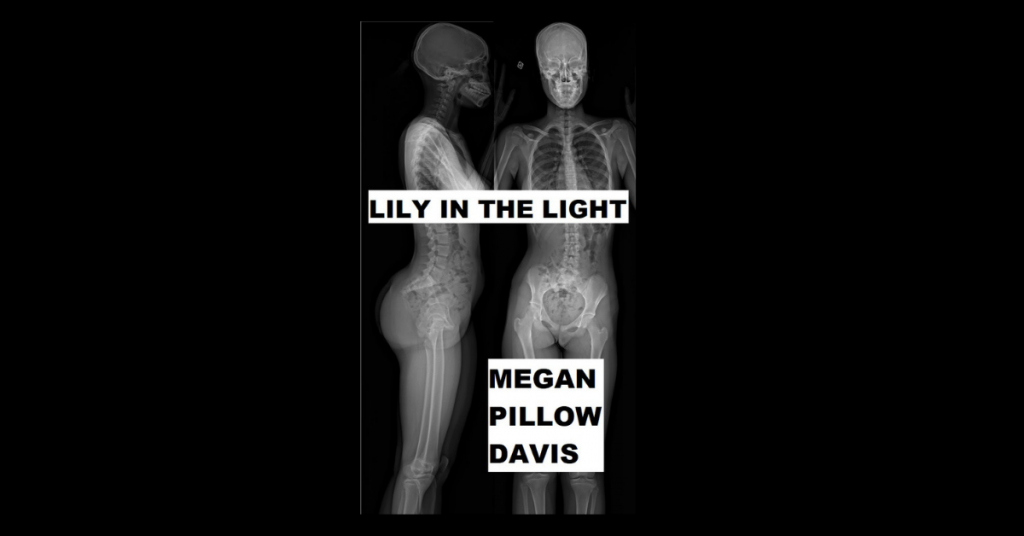

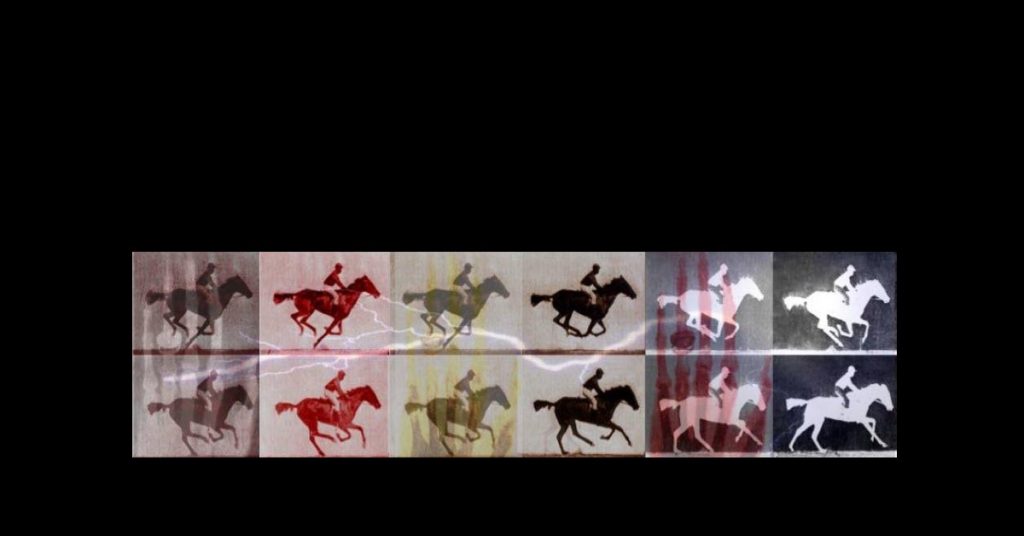

THE HORSES, THE HORSES by John Torrance (Megan Pillow)

All in all, it’s a good place to stop for the night. There’s little work to be done and a beauty of a view: a tranquil lake at the bottom of a grassy hill, lush and electric green beneath the early evening sun. No other cattle to crowd them. After they put up tents, perhaps a bit of play to shake off the day’s ride: a tune on Morton’s banjo. Then grass for the cattle and grub for the men: canned beans, or maybe a rabbit that’s a touch too slow, something that makes the belly full without turning it….