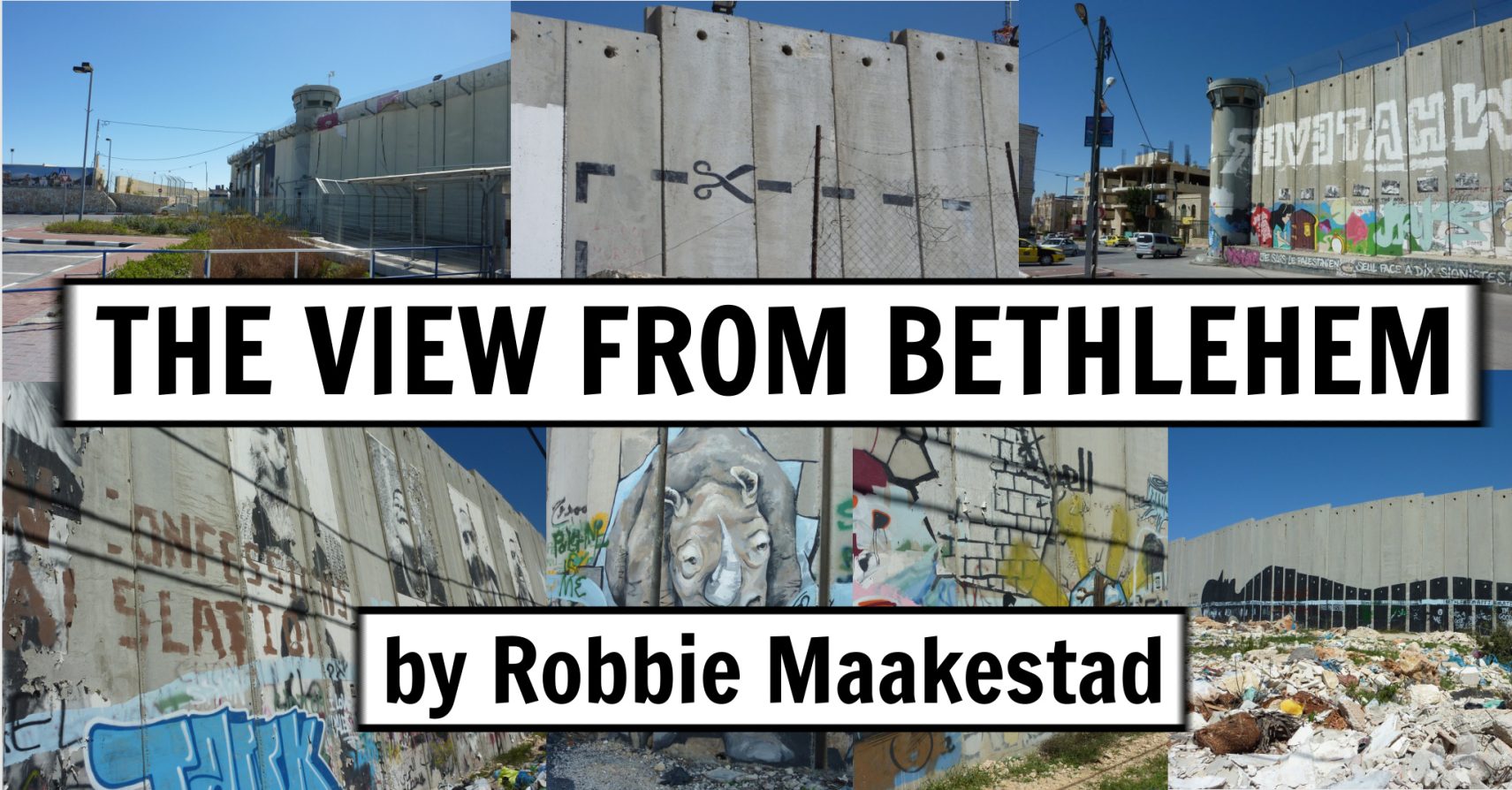

THE VIEW FROM BETHLEHEM by Robbie Maakestad

Israel Defense Force (IDF) Soldier: “What the fuck are you doing?” Banksy: “You’ll have to wait until it’s finished.” IDF Soldier (to subordinates): “Safeties off!” —Banksy’s account of painting the West Bank wall, 2005 Blue and white guard rails shepherded us from a bus stop toward the low, sprawling Checkpoint 300 gate complex outside of Bethlehem where my friend and I planned to cross from Israel on foot into the West Bank. The imposing concrete West Bank wall stretched endlessly in both directions, reminding me of photos I’d seen of the Berlin Wall, although at 26 feet high, this…