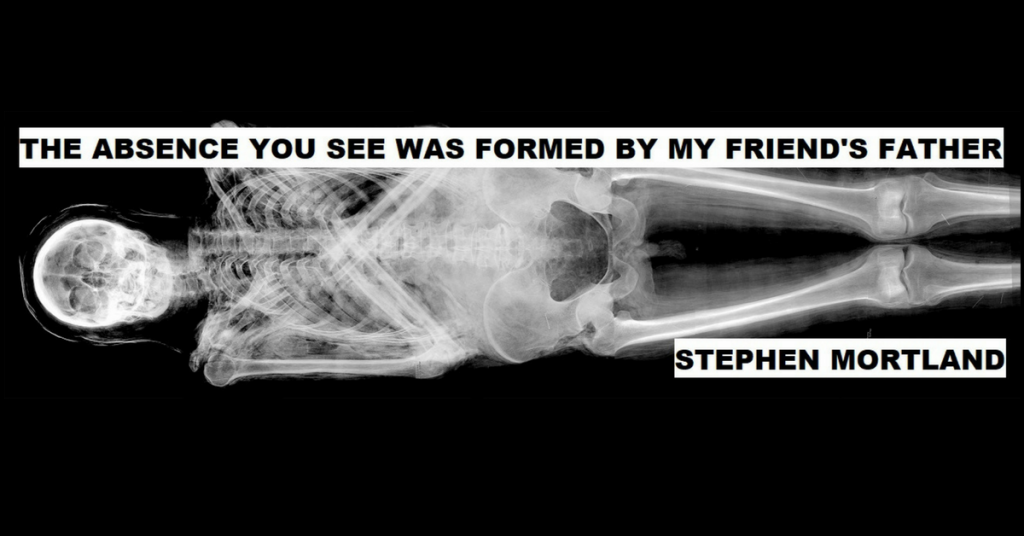

THAT ABSENCE YOU SEE WAS FORMED BY MY FRIEND’S FATHER by Stephen Mortland

JORDAN To imagine what Jordan’s dad looked like, I pictured Jordan’s face stripped of his mother’s features. It was like clearing away layers of earth to find the remains of some unidentifiable structure. The scavenged and featureless result was the face of his invisible dad. Jordan planned on changing his last name when he got married. The disembodied and scarred face of his father heard about it and showed up in Jordan’s dream the night before the wedding. “The name was fine for twenty-something years,” he said, “and now what, it’s not?” “I learned how to wear your name,” Jordan…