B.R. Yeager is not so much a writer as a contortionist, bending the human heart into impossible shapes. In his new short story collection Burn You the Fuck Alive (Apocalypse Party, March 2023), Yeager reminds us that we are all interconnected; terrifyingly and tragically so. The wounds we inflict are the same ones we inhabit, and our screams are the screams of a million voices, begging to be loved as the worst and most fucked-up versions of ourselves. When there is nowhere else to go, when you are led back to the sites of your first unravelings, you can lie to yourself; pretend you don’t see it. But in Yeager’s work, there is no escape. The part of yourself you so desperately wished to forget is coming to greet you, teeth and claws extended.

B.R. Yeager is not so much a writer as a contortionist, bending the human heart into impossible shapes. In his new short story collection Burn You the Fuck Alive (Apocalypse Party, March 2023), Yeager reminds us that we are all interconnected; terrifyingly and tragically so. The wounds we inflict are the same ones we inhabit, and our screams are the screams of a million voices, begging to be loved as the worst and most fucked-up versions of ourselves. When there is nowhere else to go, when you are led back to the sites of your first unravelings, you can lie to yourself; pretend you don’t see it. But in Yeager’s work, there is no escape. The part of yourself you so desperately wished to forget is coming to greet you, teeth and claws extended.

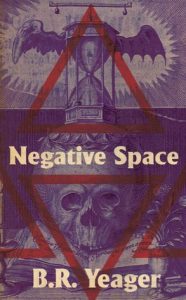

A truly inimitable writer, Yeager’s last novel with Apocalypse Party, Negative Space, had sold 10,000 copies as of November 2022. Its many fans include the lauded sci-fi writer Jeff VanderMeer, who kept it on his bedside table. But as great artists are wont to do, Yeager’s committed to writing himself into new territories, and his latest projects lack the horror bent that brought many to love him in the first place. But have no fear: I suspect Yeager will find fresh ways to haunt us well into the future.

Daisuke Shen: First of all, I want to say that this is the most gore I’ve read in one book in a long time, and I don’t think anyone but you could’ve kept me reading (and enjoying) it for the entirety of 380 pages. Thank you for allowing me to find pleasure in all this filth.

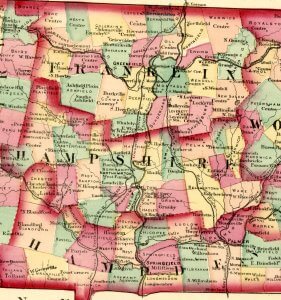

Second, I am not at all familiar with Massachusetts. How does location affect your characters in their propensity to violence? What would you like for those of us who aren’t from this region to know about your home state?

B.R. Yeager: I’ve only ever lived in Massachusetts, specifically Western Massachusetts, so I honestly have little to compare it to. I’ve visited other places, but I don’t think you can ever truly know a place unless you’ve lived there a while. And because I’ve been here my whole life, it’s difficult for me to compartmentalize which characteristics are specific to Western Massachusetts and which are just part of existing. Ultimately, like anywhere, it’s a culturally complex place. And it’s a compressed complexity. Within a two hour drive, north to south, you’ll pass depressed ex-mill towns, farmlands, the Yankee Candle flagship, affluent college towns named for proponents of genocide, Emily Dickinson’s house; the city that used to be the world’s largest paper manufacturer, and the city that birthed basketball–both now in heavy economic decline. Vast woods. Abandoned suburbs. A tunnel carved through a mountain. So many ghosts. Fairs in September. An absurd amount of music that will never escape the state. Rivers and ruins. I don’t know, I only have my own narrow perspective. Any summary feels insufficient in truly capturing this place.

B.R. Yeager: I’ve only ever lived in Massachusetts, specifically Western Massachusetts, so I honestly have little to compare it to. I’ve visited other places, but I don’t think you can ever truly know a place unless you’ve lived there a while. And because I’ve been here my whole life, it’s difficult for me to compartmentalize which characteristics are specific to Western Massachusetts and which are just part of existing. Ultimately, like anywhere, it’s a culturally complex place. And it’s a compressed complexity. Within a two hour drive, north to south, you’ll pass depressed ex-mill towns, farmlands, the Yankee Candle flagship, affluent college towns named for proponents of genocide, Emily Dickinson’s house; the city that used to be the world’s largest paper manufacturer, and the city that birthed basketball–both now in heavy economic decline. Vast woods. Abandoned suburbs. A tunnel carved through a mountain. So many ghosts. Fairs in September. An absurd amount of music that will never escape the state. Rivers and ruins. I don’t know, I only have my own narrow perspective. Any summary feels insufficient in truly capturing this place.

I honestly don’t know where the violence in these stories comes from. It’s just something I’m inclined toward in my writing. It’s almost like a tool for learning who the characters are. Because the violence itself is always less interesting than what surrounds it–the motive and echo; the ways it’s ignored, rationalized, or normalized. Or the ways fear can encourage interpersonal violence. Western Mass is a more segregated region than people like to admit, and it can be horrifically classist, with some towns posing as progressive utopias while also harboring real cultures of animosity toward homeless people and others they think do not belong. There can be a bit of an isolationist mentality. It wasn’t a conscious decision, but I imagine these attitudes informed the violence in these stories–violence emerging from a general fear and distrust of others.

DS: What you said about understanding the source of the violence and thereby understanding the source of their fear is really evident, by which I mean you listen to these characters in ways people around them rarely seem to. Torture, murder, assault—these are abnormal, depraved things that most of us want to ignore in daily life. But you don’t allow us to look away; you’re saying, “No, look at what happens to a person when they’re broken by life. Look at what happens when they’re deprived of common human respect or dignity—either by themselves or others.” And our hearts do shatter whether or not we want them to, whether we want to feel empathy for them or not.

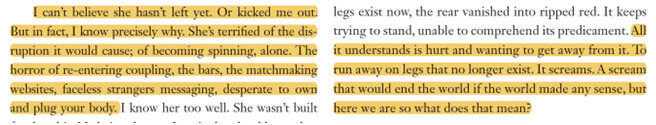

I highlighted so many lines in this PDF (and can’t wait to do so again when I purchase a print copy!) while reading, but the most I highlighted in a single story was in “Highway Wars”:

The first quote is referring to the narrator’s wife, the second, after we see him hit a deer. He works in a call center, where he performs pretty poorly at his job. He feels very weak, and taking it out on other drivers makes him regain some of that lost power. But the most haunting part isn’t that he has an inability to feel others’ pain; it’s that he feels it all too much: “The illusion breaks. I’m here. I’m something, and so is the world. I’m here and so is everybody else.”

Do you remember when you first realized that your life was inseparable from the lives of others, from the pain of human history? How did this realization push you into becoming the multifaceted artist you are today (writing, music, video, etc.)?

BRY: Thank you, that really means a lot. My aim is for the violence to never to feel gratuitous or scatological, and instead feel meaningful and emotional, but whether I succeed is ultimately for other people to determine. Psychopathy and sociopathy as motivation for violence has long been extremely boring in fiction (but very fascinating in reality, and far more nuanced and complex than is often depicted), so I tend to avoid it.

When I was a young child, I was extremely sensitive. Very anxious, very easily upset and very easily frightened. Then, from high school to the start of my twenties, I purposefully tried to numb myself to the feelings of others, and to my own emotions. I think I did so as a protective measure, maybe misinterpreting vulnerability as weakness, while also denying a lot of self-hatred. I became very callous and insensitive, very self-absorbed and entitled. This naturally put a massive strain on my relationships, leading to some friendships and romantic relationships collapsing. I was stunted in a lot of ways, and had to intentionally re-learn empathy. It was hard–recognizing how I’d hurt people, how my actions impacted others, trying to understand their perspectives and motivations. Admitting and taking responsibility for my fuck ups. All things I’d previously tried to block out. It’s still an ongoing process, because no matter how self-aware you are you’re inevitably going to keep fucking up. But even though it’s painful it leads to a far richer existence.

One thing I often talk about with my film maker friend Nick Verdi, is how we never want to create a character who’s strictly just a fucked up guy to gawk at. When our characters behave in monstrous ways, we’re using our own potential for monstrousness as a template, which I think prevents it from being a surface-level depiction. We may not know what it’s like to murder another person, but we certainly know what it’s like to be cruel, or hurt someone out of fear. We know firsthand how easy it can be to self-rationalize shitty behavior, and what it’s like to build a cell out of that self-rationalization, and the ways it corrodes the self.

DS: On this note, young people often appear as main characters in your work, both in Burn You as well as in Negative Space, where we have a cast of rotating teenage narrators. And you write them with such accuracy, such fullness, it’s almost impossible for us as readers to not be transported back into a time where we were also 16, 17, whirling masses of hate and desire, shame and confusion.

What can we, as writers, learn from young people? And what do you think your younger narrators can tell us that the adult ones cannot?

BRY: So the reason I’ve written so much about young people is simply because there are so many experiences from that period to pull from. None of my work is autobiographical, but I pull so much from real experiences that I or people I’ve known have had. Plus, as I approach forty, I have a lot more perspective about being a teen or in my twenties than I did while I was actually living those ages, making it easier for me to contextualize those experiences.

One benefit of writing these young characters is that they’re often experiencing things for the first time, and working through these major formative events, which can be very dramatic. There are also all these big, intense emotions that lend really well to melodrama. Everyone is in the process of defining and redefining themselves, identities are in flux, and those are all things I find very narratively exciting. Compared to where I’m at now, where much of my life is far more routine and established–pleasantly so, but not particularly conducive to narrative–there’s less drama and overall intensity to pull from.

That said, I ended up hitting a wall while writing Burn You the Fuck Alive. I just don’t think I can write about teens and twenty-somethings anymore–that well is tapped. But as I approach forty, I’m developing a greater perspective and understanding of my thirties, and I’m much more interested in mining that period. The novel I’m working on now is all about people in their thirties, and it’s completely divorced from many other elements I’ve become known for. No internet, no drugs, no horror. Burn You the Fuck Alive is essentially the end of a cycle, and I’m closing a door on many of the themes I’ve focused on the past eight or so years.

DS: I’d love to know how writing a short story collection felt for you in terms of process, as I generally know you as a novelist. What changed, if anything?

BRY: Really, I was just trying to re-learn how to write. The editing and polishing process for Negative Space was so long and intensive, by the time I was finished I’d largely forgotten what it was like to start from scratch. I’m not someone who is able to write something and have it come out immediately beautiful. It’s really the editing process that turns it into something decent, so until I have enough material to edit I’m just tapping out these ugly sentences into an ugly structure and I have to trick myself into believing I’ll someday be able to turn it all into something worth reading.

BRY: Really, I was just trying to re-learn how to write. The editing and polishing process for Negative Space was so long and intensive, by the time I was finished I’d largely forgotten what it was like to start from scratch. I’m not someone who is able to write something and have it come out immediately beautiful. It’s really the editing process that turns it into something decent, so until I have enough material to edit I’m just tapping out these ugly sentences into an ugly structure and I have to trick myself into believing I’ll someday be able to turn it all into something worth reading.

Once Negative Space was out, I was fortunate enough to be approached by several editors asking if I could contribute stories to anthologies. So I ended up generating a batch of short fiction, with each piece helping me reacquaint myself with the writing process, start to finish. Short fiction also encouraged me to experiment and play around with ideas that I may have thought were cool but not sustainable for an entire book. I was trying to figure out what really makes a story satisfying on a structural level, which is probably one reason a lot of these stories are closer to traditional genre fiction than my previous books. There’s my first attempt at noir, my first attempt at erotica, and my most traditional horror story in there. Just seeing what I could do with various structures. At my most pessimistic I’ve worried that this collection is akin to charging people to watch me at the gym; when I’m more optimistic, it feels like I’m just flexing in different genres. As always, it’s up to others to ultimately decide which it is.

I did end up falling in love with the novelette as a form. Fourteen-thousand words is a beautiful space to play around in. Enough space to capture some mood and establish the feeling of a real world, but you’re still getting in and out. I have other stuff I need to finish first, but I’d love to write some more novelettes in the future.

Read Rebecca Gransden’s interview with B.R. Yeager from our archives.