Opening your eyes at night, unsure of where you are, half-dreaming, half-awake…staring into the darkness of a living room, thinking that the shadow near the door might be a man…or a coat rack… the tremble along your spine as you hear the voice of a deceased loved one on your voicemail…the uncanny sight of a mannequin that may or may not be a living person. We all know that sense of dread that comes from uncertainty during transitional moments, as well as the relief we feel once we settle into the known.

Below are a list of fiction books that are highly effective at making the reader feel as if they are occupying a space in between: between real and fantastical, normal and paranormal, waking and dream, self and other, sanity and madness, life and death. Some are surreal, some evoke the uncanny; some use absurdity and humor, some play with expectations of form and structure; and some distort language itself to evoke a liminal state.

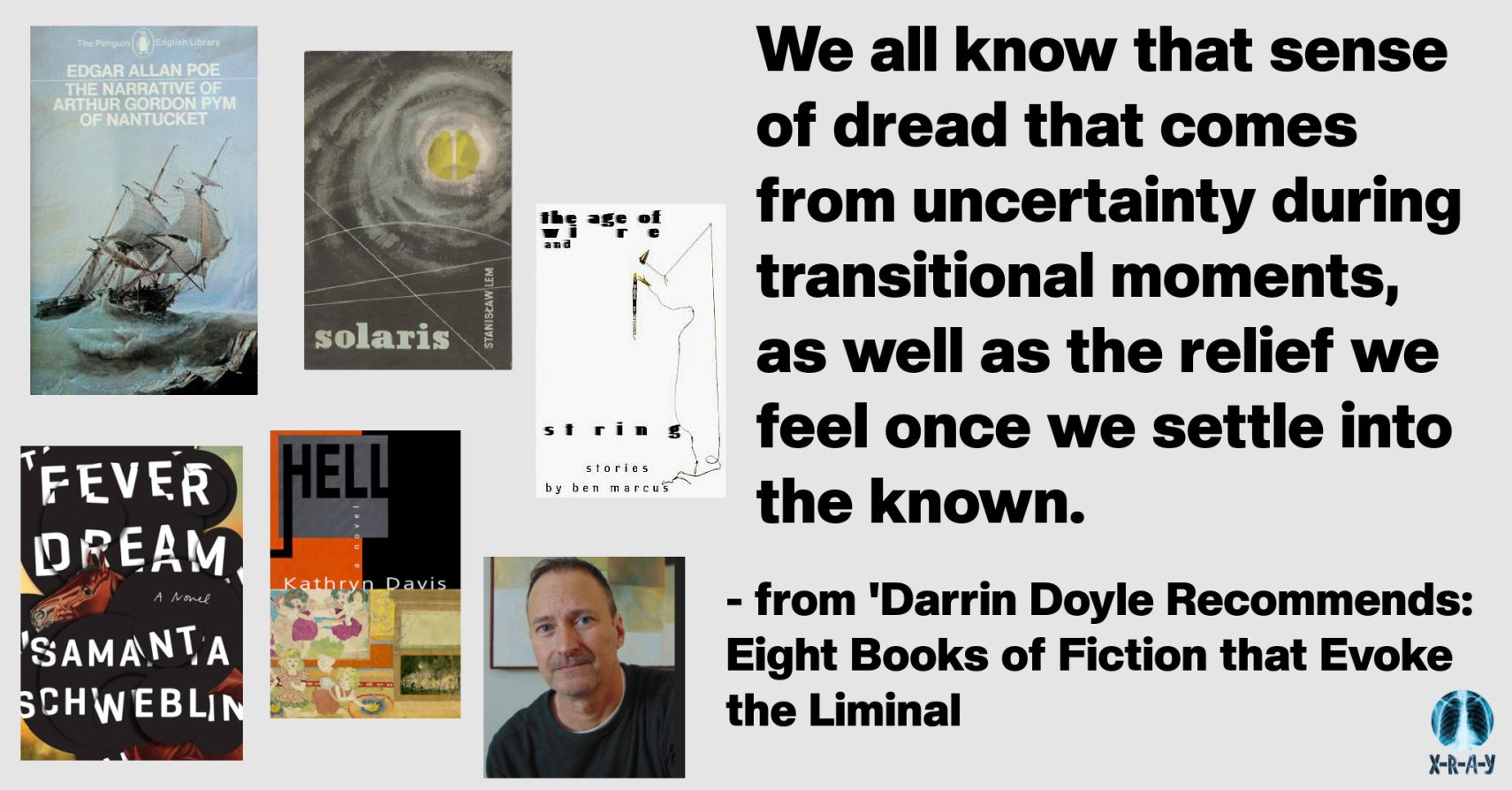

Fever Dream by Samanta Schweblin (Riverhead Books, 2017)

“She’s not his mother. He’s not her child.” This statement on the jacket flap forecasts the oddness of this novella, which tells the story of a dying woman, Amanda, who is speaking to David, the child of a woman named Carla. David has previously been saved from death after ingesting a poisonous liquid, but the process of saving him has changed him into an uncanny version of himself, as if he’s now lacking a soul or spirit. Amanda is trying to figure out what happened to herself as well as to help her daughter Nina. Much of the story is told in dialogue, with no quotation marks, which is just one way Schweblin creates a fluidity of identity and a dreamlike state. Schweblin also plays with narrative structure, creating an enigmatic atmosphere as we try to figure out what truly happened. The result is an eerie existential tale that lives up to its title.

In the House by Lyn Kilpatrick (The University of Alabama Press, 2010)

This is a wildly unique story collection, each piece revolving around domestic spaces. Kilpatrick employs formal invention and a poetic, figurative lens to create a sense of liminality between psychological and physical, between exterior spaces and interior spaces. Kilpatrick uses lists, instructions, diary entries, directions, character sketches, and more. In one series of flash pieces, each titled “Diorama,” the reader explores ordinary household situations through the uncanny use of toys and figurines meant to represent reality. The result is a creepy, sad, thoughtful meditation on the thin line between danger and safety in our domestic lives.

The Narrative of Arthur Gordon Pym of Nantucket by Edgar Allan Poe (Harper, 1838)

One of the founding fathers of liminal fiction in American letters, Edgar Allan Poe’s longest story is also one of his strangest. I’m oversimplifying quite a bit here, but this novel features (among other things): a man stowing away on a ship and nearly starving in the cramped space; there’s a violent mutiny; there’s a shipwreck; there’s a boat full of rotting corpses; there’s cannibalism. Eventually the story takes us to a bizarro Antarctic landscape where the water is thick and laced with veins. Poe’s familiar themes of claustrophobia give way to fear of the other, fear of the irrational, and fear of mental stability giving way to madness.

The Age of Wire and String by Ben Marcus (Alfred A. Knopf, 1995)

One of the most unique and challenging fiction books I’ve ever read, The Age of Wire and String does nothing short of redefine the English language, providing new, wildly strange definitions to common words. It’s less a story collection than a glossary of terms, a catalogue of a parallel universe. Marcus eschews standard story elements like character and plot in favor of a swirling, befuddling, funny, and surprisingly enlightening journey through a defamiliarized landscape that resembles our world but is wholly new. My biggest takeaway is how strongly our concepts of “truth” and “reality” are determined by the words we use, the names we call things – and when these definitions are destabilized, we’re thrust into liminal chaos.

Hell by Kathryn Davis (Ecco Press, 1998)

This is one of my all-time favorite novels, and it’s been hugely influential on me as a writer. Hell employs three distinct spaces/narratives: 1950s Philadelphia, 1700s France (featuring Napoleon’s chef), and a dollhouse in the 1950s Philadelphia home. We’ve all seen novels with multiple timelines and settings, but the brilliance of Davis’s novel is seeing these spaces/times gradually blend and converge, intruding on each other quietly and persistently until reality becomes a blurred distortion. By breaking down the normal barriers that delineate time and space, our comfort and sanity are put to the test. The novel is terrifying, bewildering, and one-of-a-kind.

The Week by Joanna Ruocco (The Elephants, 2017)

This collection explores the liminal space of storytelling, the way stories themselves can place us in a transitional state by raising questions about intention, purpose, and narrative stance. How does one categorize these pieces? Ranging from a few sentences to about four pages in length, they eschew traditional fiction components at every turn. Many read like stream-of-conscious rants (Instructions? Meditations?) that may or may not connect to their titles. Take “Well,” for example, which begins: “The human body is not a good place to store things, not if you want them to keep. If you want things to spoil, then, fine, put them in the human body. Put a head of lettuce in your body, it will wilt in the heat, the cellulose will turn to slime.”

The Rumphulus by Joseph Peterson (University of Iowa Press, 2020)

This delightful read from one of Chicago’s best writers tells the story of a forest inhabited by men. These are men who have been banished from society, forced to live in the wild. They’ve each been condemned, though none of them seem to know what their transgressions were. Franz Kafka is one of the most well-known writers of the liminal (I could have included any of his works on this list), and The Rumphulus is definitely a Kafka relative. This novel takes (and gives) great pleasure through resistance: to rules of logic, of human behavior, of conflict and character development, and even rules of grammar.

Solaris by Stanislaw Lem (Wydawnictwo Ministerstwa Obrony Narodowej, 1961)

This classic science fiction novel has been adapted into film a couple of times with varying degrees of success, but I personally don’t think either adaptation captures the spooky, unsettled feeling of the novel, which bends reality so thoroughly and consistently that a reader feels trapped in a prison of dread. The story finds a crew of scientists living on a planet named Solaris, and each of them start to experience visions and manifestations – actual embodiments, it seems, of repressed memories. Are these ghosts? Are they real? Or are they simply phantoms created by the psyche? The novel never gives easy answers to these questions. Instead, we’re left to squirm with uncertainty just like the characters.

A revised tenth anniversary edition of Darrin Doyle’s The Dark Will End the Dark features a new introduction by American Mythology author Giano Cromley. Released October 2025 by Tortoise Books.