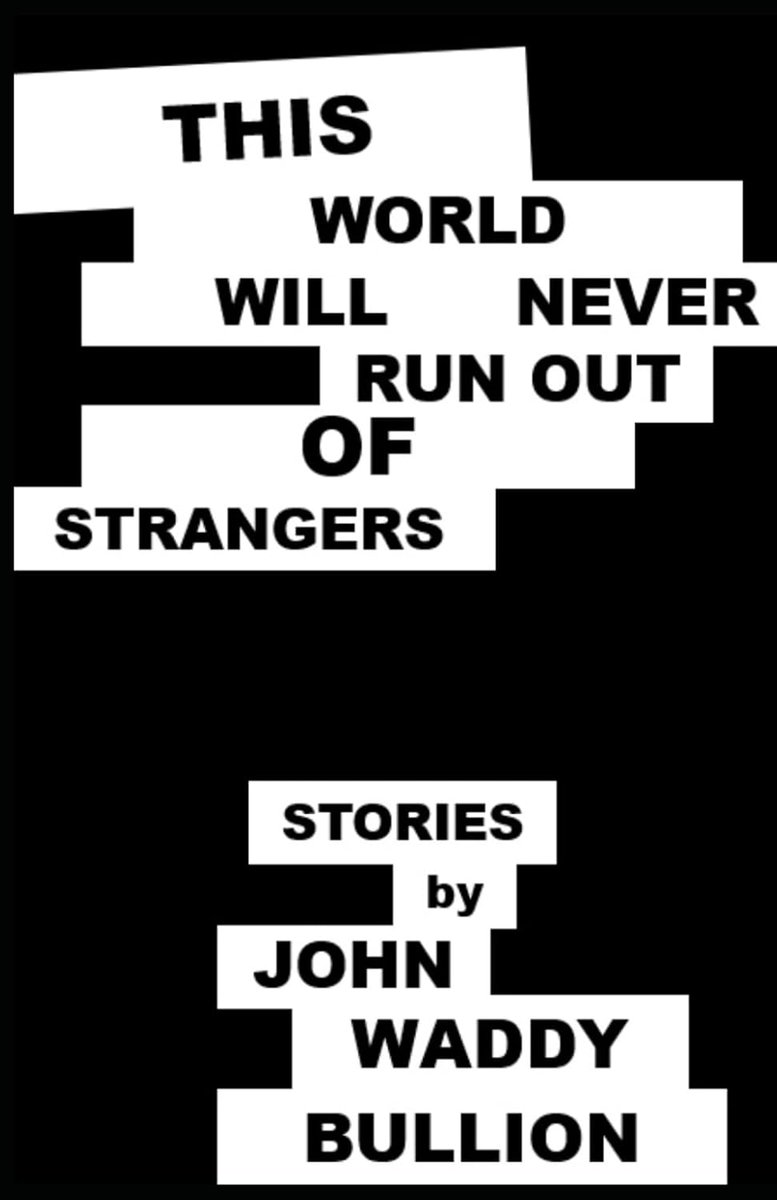

John Waddy Bullion is as versatile a writer as they come. His loosely-linked collection This World Will Never Run Out of Strangers follows coming-of-age tales of Midwestern sons and the fraught relationships they have with role models: fathers, grandfathers, uncles, peers, sports heroes. It’s also a showcase of Bullion at his best: forever balancing humor with pathos, mastering pop culture and sports references, commanding attention from first page to last. It’s a collection that’s quick to devour and demands re-reading; Cowboy Jamboree Press was smart to pick it up, and you can grab your copy here.

John Waddy Bullion is as versatile a writer as they come. His loosely-linked collection This World Will Never Run Out of Strangers follows coming-of-age tales of Midwestern sons and the fraught relationships they have with role models: fathers, grandfathers, uncles, peers, sports heroes. It’s also a showcase of Bullion at his best: forever balancing humor with pathos, mastering pop culture and sports references, commanding attention from first page to last. It’s a collection that’s quick to devour and demands re-reading; Cowboy Jamboree Press was smart to pick it up, and you can grab your copy here.

Ahead of its November 18 release, I had the pleasure of being able to pick John’s brain about the collection. I’ve been a big fan of John’s work for a long time, so excuse me as I nerd out.

MacKenzie: Talk to me about structure. How did you arrive at the final collection?

Bullion: I’ve always viewed the collection’s last story (“Two Bibson Geefeaters”) as a natural end point. But there were times where I felt completely stumped about how to order the other eight, all of which employ varying lengths and stylistic approaches. There are at least three stories that I believed could function as a “first story,” but ultimately, it became clear that if the collection was going to end with Gaylord, it probably needed to begin with him, too. “Up n’ Comers” isn’t the first chronological story (that would actually be “Aristotle’s Afterthought”), but placing it first helped put enough distance between that story and “Two Bibson Geefeaters,” half of which which essentially retells the events of “Up n’ Comers.”

Please understand that I never would’ve arrived at these realizations about structure on my own. I had considerable help from Kirsten Reneau, who is a master at structuring collections (she played a huge role in helping Kyle Seibel sequence Hey You Assholes). Kirsten helped me see a path forward in terms of order, and I would recommend her services as an editor (and an orderer) to anyone.

MacKenzie: Many of these stories are preoccupied with male role models. There is a tender, flawed masculinity on display in your sons, fathers, uncles, grandfathers, and peers. The relationships between them are keenly drawn. Was that influence consciously on your mind as you were writing?

MacKenzie: Many of these stories are preoccupied with male role models. There is a tender, flawed masculinity on display in your sons, fathers, uncles, grandfathers, and peers. The relationships between them are keenly drawn. Was that influence consciously on your mind as you were writing?

Bullion: The disintegration of Gaylord’s parents’ marriage is basically a funhouse mirror version of my own childhood, which was abnormally happy, and my parents, who were supportive, present, and only separated in age by six months, not a couple of decades. But I had friends whose parents were a lot like mine (professors, librarians, grad students, librarians, etc.), and in many of those marriages between academics, the fault lines were a lot more apparent, especially with the way husbands/fathers in those unions sometimes conducted themselves in a college town environment. Maybe it has something to do with the whole academic tenure thing, where it doesn’t matter what you say or do, if you have tenure, you’re protected. There’s also that Latin term, in loco parentis—literally, in place of parents. Bearing that kind of dual responsibility while operating in a space where you are told that you can say or do whatever you want produces a strange kind of tension, and that tension has a tendency to seep into and warp the domestic relationships within the “gown” elements of town-and-gown.

MacKenzie: Similarly, many of these stories are preoccupied with the razor’s edge between youth and adulthood, and how that gap is collapsed in the presence of adults unable to act safely, sanely, or selflessly. Tell me your thoughts around coming of age in these stories, particularly at this specific moment in history (the 80s and 90s)?

Bullion: It’s interesting to consider specificity surrounding a certain time period because I will be the first to admit that I play pretty fast and loose with time in these stories. Although it’s never explicitly stated in the narrative, the events of “Aristotle’s Afterthought” take place on August 22nd, 1986. (I know this because I matched the beats of this exact baseball game to the events of the story. It was simultaneously a really fun challenge and something I will never, ever put myself through again.). Gaylord would’ve been roughly 8 years old in “Aristotle’s Afterthought,” but in “How to Ask a Stranger to Buy You Beer,” which takes place on Thanksgiving weekend, 1998, he’s about 13 or 14.

One of my favorite William Faulkner stories, “That Evening Sun,” is narrated by an adult Quentin Compson, presumably aged twenty-four—the same Quentin Compson who leapt to his death off the Great Bridge as a nineteen-year-old Harvard student in The Sound and the Fury. Faulkner didn’t give a shit about temporal inconsistencies, so why should I? That was all the permission I needed. More practically, however, I wanted these stories to be able to stand on their own and not be dragged down by the weight of linkage. My view of linked stories is that they should absolutely amplify and echo each other, but they cannot depend on each other. That’s a huge part of the reason that the version of the events presented in “Up n’ Comers” is re-told in a slightly different way in flashback in “Two Bibson Geefeaters.”

But to return to the coming-of-age aspect of your question, I see Gaylord as a superhero. He can come of age in the ‘80’s, 90’s, and even the 00’s. He can also fall in love with his father’s mistress Daphne as a ten-year-old and then fall in love with a different Daphne as a college student. Or is it actually a different Daphne? Did Gaylord steal his father’s girlfriend, run off with her to Texas, and concoct a wild cover story as a stab at normalcy? Is there a thumb drive somewhere in my office with an aborted novella where this exact thing happens? I guess we’ll never know.

MacKenzie: One hallmark of a John Waddy Bullion story is a good pop culture or sports reference. Specifically, in these stories, you ground the reader in time with quarterbacks, pitchers, and play-by-play announcers. You are so goddamned good at having a light touch when it comes to these references; they never feel like the focal point, and yet they carry as much narrative weight as any other detail. How did you see the relationship between time, and memory, and sports for these characters?

Bullion: Around 2017, there was a meme format that spread through sports Twitter like wildfire called “let’s remember some guys.” Basically, this meme involves throwing out the names of obscure, retired athletes lost to the ravages of time. The more average or unremarkable these guys are, the better. John Tudor (baseball) and Elvis Grbac (football) are, to me, the absolute ne plus ultra of “let’s remember some guys” for Missouri professional sports, and they are practically main characters in “Aristotle’s Afterthought” and “How to Ask a Stranger to Buy You Beer,” respectively.

John Tudor had a reputation as a hothead and was most notorious for his electric fan-punching incident after he bungled Game 7 of the 1985 World Series. But the little biographical anecdote I found about the adjustment Tudor made to his pitching mechanics earlier that season fit perfectly with that story’s examination of afterthoughts as something ignored, elided, skimmed over, and neglected (consciously or unconsciously). Elvis Grbac’s main claim to fame is that People magazine accidentally named him the Sexiest Athlete Alive in 1998 and everyone just kinda rolled with it. But when I came across that info-nugget about the speaker in his helmet malfunctioning in the divisional playoffs (the moment Grbac lost his “how-to” manual), I knew I had to use it in “How to Ask a Stranger to Buy You Beer.” Did I have to go to these lengths? Absolutely not. But maybe—and this might be where time and memory come in–my nightmare fear was that some sports-nerd pedant like me would stumble across either of these stories and point out where I’d gotten some detail wrong. If I was going to use those references, they had to have that extra resonance to be able to withstand the Google stress-test.

MacKenzie: One thing you’re also particularly adept at is playing with form. How does versatility of form allow you to stretch your legs and challenge yourself, narratively?

Bullion: For a while there, it felt like 7,000 word stories were all I was capable of writing. Here’s the thing about 7,000 word stories: they take forever to write, and they are insanely difficult to publish. The shorter form is something I’d been really challenging myself to really experiment with, but first I had to overcome my mental block of not being able to write more flash-length stuff. I think the shorter interstitial pieces in This World Will Never Run Out of Strangers are me finding an approach that clicked. These shorter pieces are heavily premise-based, and flirt as much with being straight humor pieces as they do literary flash. And while I’m not a big fan of the term “hermit crab,” it does help me to work within the shell of a form, whether that’s a rejection letter (“Dear Entrepreneur”), a press conference (“Star Quarterback Addresses Media after Fiction Workshop”), or a list of contributor biographies (“Contributor Bios”). In the end, though, it’s all about having a sense of which stories need to be short, and which ones need more room to spread out. For me, it comes down to a certain kind of trust, that whatever you’re working on is going to tell you exactly how long it should be. And yeah, maybe I’m a little more adept at writing shorter stuff now, but that has also presented me with a new problem: lately I can’t seem to write anything over 2,500 words.

Kirsti: Given that you’re in Texas, I was surprised to see the Midwest featured so prominently as a setting in the linked stories. Walk me through the choice to place most of the stories in Missouri, in a college town of Montessori schools and “the Midwestern Ivy”.

Bullion: I grew up in Columbia, Missouri, but my parents were both Texas expats. (My mom missed San Antonio so much during her first winter up north that she placed a long-distance call to her favorite taqueria and somehow strong-armed them into sending her frozen tamales through the US mail.). Growing up with a foot in both worlds meant I never felt like I fully belonged to either place, which in its way proved useful. The Missouri city where most of the Gaylord stories are set is never named. (I couldn’t very well set it in Columbia, because Stoner beat me to it.). But I wanted to give myself the leeway to make it an amalgam of several different places I’ve lived or worked. The one Texas story in the collection (“Two Bibson Geefeaters”) is explicitly set in San Marcos, which is my favorite city in Texas, and I happily threw in as many specific places and things and local quirks as I could remember from my time there. People, too: Gaylord’s grandfather’s first appearance (as a shirtless man throwing a Frisbee around San Marcos’s notorious “Bikini Hill”) is based directly on Frisbee Dan, one of the many marvelous “San Martians” who make that place so unique. Eat that, Stoner.

MacKenzie: Gaylord’s stories felt to me like the germination of a novel—were they originally written with that aim in mind? What was it about his story that tugged you to develop a linked collection?

Bullion: “Up n’ Comers,” the first story in the book, was the first story I wrote with this set of characters, and with Gaylord at the center. Writing a novel-in-stories was (and in a lot of ways, still is) way more appealing to me than writing an actual novel. One of my favorite writers, George Singleton, has said in interviews that he prefers to write linked stories because they’re easy to re-package as a novel, and thus easier to sell. While that wasn’t necessarily my goal, the Gaylord stories were never part of a larger “novel”—I just saw them as individual stories that happened to feature the same characters. I believe that the linked stories in this collection tell a complete story, but they resonate across the collection, even in the works where they may only share a setting, or even something as tenuous as a shared feeling.

MacKenzie: There is a trick you often pull with humor. It’s so dry and so quick in your stories that if you are not paying attention, you might miss a punch line, or a bit. It demands more from the reader, and rewards rereading. Like with your pop culture and sports references, it’s a lighter touch. I am an audience member in front of a magician, demanding to know his trick. How do you manage it?

Bullion: This is gonna sound weird, but I often forget that my stories are funny. I read an excerpt from “How to Ask a Stranger to Buy You Beer” at the Little Engines “Morning, Fuckers” reading in Dallas this past year and I remember being honestly startled by the amount of laughter it got. That story feels almost unbearably heavy to me–in a lot of ways, I consider it to be the most tragic story in the book. But while I don’t set out trying to be funny, I do want to write in a voice that’s natural and authentic–it just so happens that humor is a big part of that naturalism and authenticity. George Singleton, as I’ve mentioned, is a huge influence on my writing—he was one of the first writers I encountered whose writing sounded like I wanted mine to sound. Singleton’s stories are hilarious, but he also writes these wonderfully complicated, information-packed sentences, which allows him not only to layer in a lot of humor and absurdity, but also to sneak in emotional gut punches. I want my writing to have all of that, but I don’t want any one feeling to override or unbalance the other, hence the lighter touch.

MacKenzie: When Gaylord’s grandfather saves him from dropping a loaded barbell on his windpipe in the final story, he questions whether the man is real, or an apparition. The grandfather then invites him to throw a haymaker, which Gaylord can’t: “I knew that knowing would be the end of me.” Tell me about the need to cling to an idealized version of a father, instead of the reality.

Bullion: I think the male figures in Gaylord’s life are two poles of masculinity: Gaylord’s father (“the Professor”) represents intellect, while his Grandpa is an avatar for physical strength. Both of those masculine identities have been destructive, but they’re also areas where Gaylord feels this constant need to prove himself, only to keep falling short. By the end of the book, I think he does start to sense a possible third path opening up for him, although it’s a path that he isn’t quite able to articulate or act upon. After the final line of “Two Bibson Geefeaters,” I confess that I have no idea what Gaylord is about to do next. He seems primed to do something stupid and irreversible, but he also seems just as likely to do nothing at all. But I’m comfortable with that ambiguity. Not-knowing can be the start of something, too.