PATTY by Hugh Behm-Steinberg

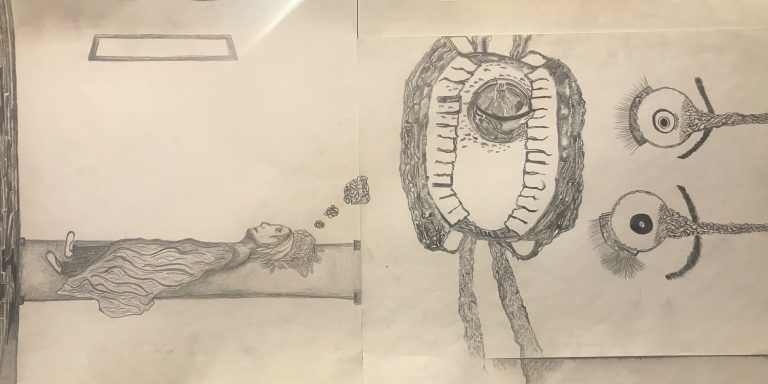

The problem with dolls who can do things is that they get bored, you have to keep them busy. If you don’t they get clingy, and it’s so easy to forget to keep the little gold chain on around their neck. They say if you forget about the little gold chain the dolls will chase you everywhere, and then it’s stab, stab, stab. But mostly they’re just you, only smaller, which is gross in its own way. As you get older, they become more childish, until finally you have to put them in a shoebox and bury them in the