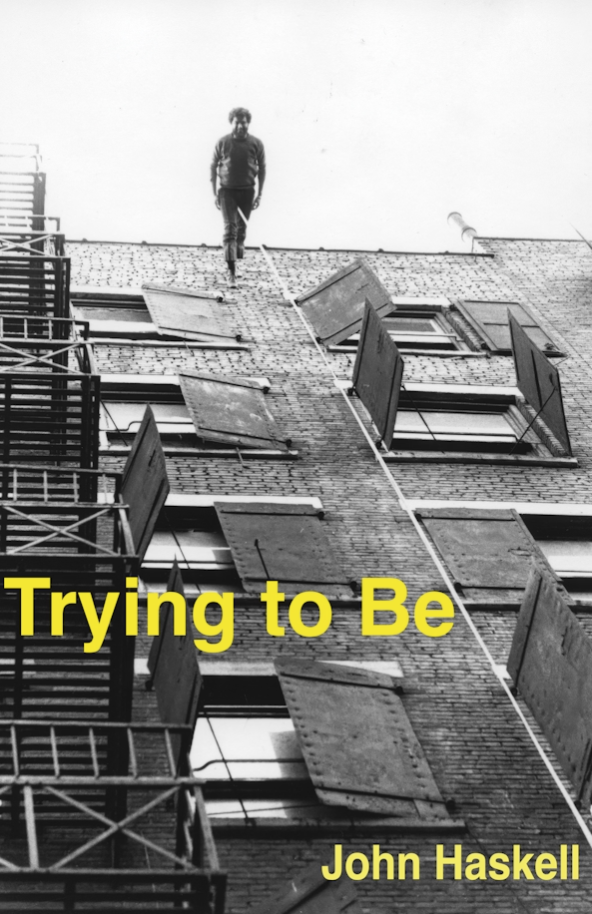

How to move. John Haskell’s Trying to Be (Fiction Collective Two, 2025) plots the potentials in life by means of undefinable and expressively changeable essays. Always shifting, the collection weaves around the central conundrums of existence, and in so doing implicates itself in this unceasing mystery. At once a humane interrogation of headspace and exploration in what it means to pass through the world as a physical being, Haskell’s work teems with the presence of the engaged observer, caught in the maelstrom we sometimes call reality. I spoke with John about this slippery and enigmatic book.

How to move. John Haskell’s Trying to Be (Fiction Collective Two, 2025) plots the potentials in life by means of undefinable and expressively changeable essays. Always shifting, the collection weaves around the central conundrums of existence, and in so doing implicates itself in this unceasing mystery. At once a humane interrogation of headspace and exploration in what it means to pass through the world as a physical being, Haskell’s work teems with the presence of the engaged observer, caught in the maelstrom we sometimes call reality. I spoke with John about this slippery and enigmatic book.

Rebecca Gransden: You utilise shift in form throughout the collection, frequently within an individual piece, whether that be the blending of memoir and fiction, change in point of view or the use of media such as film as a filter. It is a technique that can result in prose close to the way thought works, or at least the way we think about thinking. Is this a conscious stylistic choice or something that has evolved instinctually?

John Haskell: Your question (with its reference to all the various blendings in the book) urges me to answer yes. And I’m not kidding when I do. Just as the book’s point of view is fluid, and the subject matter is fluid, so is my thinking about the way I think. My style, such as it is, is both a conscious stylistic choice and part of an evolution, through years of repetition and rewriting. In terms of point of view, I’ve always looked for a way to express the fact that our individual identities as human beings are not so adamantine or monolithic. But how to express that and characterize that? That’s something I’m still trying to figure out. Which is probably why the writing in the book seems a bit like thinking. Because I am, actually, trying to figure out what to say and how to say it. And although I’m trying to be clear, sometimes what I want to say doesn’t lend itself to clarity. That’s why, when the title Trying to Be came to me one day, I was so relieved. Suddenly there was no more dillydallying. Sometimes, writing a collection of pieces like this, the question of what the title should be can drive you crazy. When I heard the words Trying to Be in my head they seemed to fit, not just the work I’d written, but the attitude I had when writing. And the words fit because every piece in this collection is about the often futile attempt to find a place in the world, and whether I use several points of view to look at the question, or whether I use film or biography or personal history, it’s all in the service of wondering how to approach what for me is a personal and pressing question. So yes, it’s both conscious, and at the same time the writing just seemed to happen.

RG: Let’s say that when I stand, with my feet on the ground and my eyes facing forward, the right side of my body is slightly shorter than the left, as if I’m holding a weighted bag in my hand and the weight of the bag is pulling me down, curving me over. Instead of standing with the verticality of a plumb line, there’s a slight arc to my torso. And however I came to this posture, via trauma or repetition or necessity, over time I’ve made it my history.

The above quote is lifted from the piece “Blow Me Away” where you feature the film Blow-Up as an instrument, among other things, to examine the relationship time has with the body. What does inhabiting the body mean to you, and what does this imply when it comes to narrative, whether that be the story we apply to our own lives, or that expressed artistically?

JH: The one thing I’ve never found in my reading life, a thing I didn’t even know I wanted or needed, was a scrupulous consideration of the fact that we all have bodies. Some are women’s bodies and some are men’s bodies but underneath the skin, all the various bodies share a number of common experiences. The first, obviously, is that they die. That’s a big one. And then there’s pain. No one can really get around that. There’s pleasure too, both physical and mental, and my point, I suppose, is that, until very recently, I didn’t know very much about my own body. I’d never been taught, for instance, where my liver was and what my liver did. The Quadratus Lumborum could’ve been an ancient god for all I knew. Part of the fun of writing about the body is discovering mine, its structure and function and its metaphorical possibilities. And I’ll also say, although it’s not really answering your question, that the old dictum to “write what you know” has always made me feel a little left out. My life, to me, doesn’t seem interesting enough or special enough to warrant writing about. That’s why I look to film and to historical figures. And also my body. That, somehow, does seem interesting, and because my body is basically like every other body on the planet, I think it serves a narrative purpose. I’m not sure what that purpose is, exactly, but I’m going to dig around and see what I find, pick at the threads and follow those threads and once I’ve unraveled them, maybe I’ll know what I’m expressing, and why.

JH: The one thing I’ve never found in my reading life, a thing I didn’t even know I wanted or needed, was a scrupulous consideration of the fact that we all have bodies. Some are women’s bodies and some are men’s bodies but underneath the skin, all the various bodies share a number of common experiences. The first, obviously, is that they die. That’s a big one. And then there’s pain. No one can really get around that. There’s pleasure too, both physical and mental, and my point, I suppose, is that, until very recently, I didn’t know very much about my own body. I’d never been taught, for instance, where my liver was and what my liver did. The Quadratus Lumborum could’ve been an ancient god for all I knew. Part of the fun of writing about the body is discovering mine, its structure and function and its metaphorical possibilities. And I’ll also say, although it’s not really answering your question, that the old dictum to “write what you know” has always made me feel a little left out. My life, to me, doesn’t seem interesting enough or special enough to warrant writing about. That’s why I look to film and to historical figures. And also my body. That, somehow, does seem interesting, and because my body is basically like every other body on the planet, I think it serves a narrative purpose. I’m not sure what that purpose is, exactly, but I’m going to dig around and see what I find, pick at the threads and follow those threads and once I’ve unraveled them, maybe I’ll know what I’m expressing, and why.

RG: I’m interested in emptiness. You touch upon the act of clearing the mind, of becoming empty. How does the concept of emptying play into the idea of trying to be?

JH: At one point in my life I was slightly lost. I say slightly but of course if you’re lost, there is no sense of “slightly.” And so I started to visit with a psychologist. I didn’t get much out of it, I don’t think, but I was introduced by this analyst to a form of meditation, and meditation, broadly, is an emptying. For me it’s an emptying of the superficial. An analogy would be when I’m lying on my back trying to relax. I let my muscles completely stop doing what they do. And when I do that, I find that the tension I was letting go of didn’t go completely away. There’s some lingering tension or effort and so I try to let go of that. And if I’m paying careful enough attention I notice there’s still some lingering tension. And I find the mind is similar. You can empty it, but once it’s empty, if you pay attention, there’s still something there. So “clearing the mind,” as you say, is not a result, it’s a process. That process is very much at the heart of Trying to Be. You find what you think is a truth, and behind that truth is something that seems a little truer, a little more concise or purer, and a metaphor I often hear is about peeling the layers of onionskin from an onion. There always seems to be another layer beneath the layer you’re just peeled.

RG: Sometimes when I’m writing, when I think an idea is about to appear but the words I have don’t quite reveal it, I get impatient. I get critical, judging both the idea and the words, inhibiting their inclination to expand and connect. And I understand the necessity of constraint, that wanting is one thing and not getting what you want is a fact of life, but still. I want my life to expand into moments that aren’t just reiterations of what I already know. And it ought to be possible.

When thinking about the collection as a whole, were there pieces that came easier than others?

JH: I wish! Every piece in the collection has been rewritten so many times, not just polished but rethought and restructured. It’s amazing to me that they still exist, that they haven’t been whittled away to nothing. I have written texts in my life that just came, as they say. First draft, best draft. That’s what Allen Ginsberg once told me (actually he told that to a lot of people. It was his Buddhist way of opening to inspiration, of a kind of thoughtlessness and spontaneity, but I find in the process of rewriting a similar kind of mind at work, and it’s not my mind, it’s the mind of the process, and the only downside is that it takes a lot of time.) I’m an admirer of Allen Ginsberg, but our approach probably differs in significant ways. And now that I think about your question a little more deeply, I guess I would say that all the pieces came easy because by rewriting them over and over and over, in retrospect at least, it wasn’t a lot of work. It was fun.

RG: Do works of art, of any and all types, arrive in your life when needed, or is their appearance seemingly arbitrary?

JH: I’m going to joke with you now and kiddingly reprimand you for having such a dualistic—binary we now say—outlook. I mean, stepping into a museum and looking for inspiration and seeing, for instance, the painting Judith Slaying Holofernes by Artemisia Gentileschi, maybe I notice the way Judith recoils from the blood gushing from Holofernes’s neck. Maybe I think about the dualism of mind and body and how Judith is severing that. I can imagine her anger at what has happened to her, and maybe it’s arbitrary but the painting triggers something in me and once that thing gets triggered it’s no longer arbitrary.

JH: I’m going to joke with you now and kiddingly reprimand you for having such a dualistic—binary we now say—outlook. I mean, stepping into a museum and looking for inspiration and seeing, for instance, the painting Judith Slaying Holofernes by Artemisia Gentileschi, maybe I notice the way Judith recoils from the blood gushing from Holofernes’s neck. Maybe I think about the dualism of mind and body and how Judith is severing that. I can imagine her anger at what has happened to her, and maybe it’s arbitrary but the painting triggers something in me and once that thing gets triggered it’s no longer arbitrary.

RG: “Role Models” centres on your aunt, a woman who lived an extraordinary life. At what point in your own life did you decide to write about her, and when that decision was made, how did you settle upon your approach to the piece?

JH: When my aunt died, I was the person who combed through her house, selling much of what she owned, saving some of what she cherished, and because I loved her I wanted to preserve as much as I could. Some of her furniture I have now in the house where I live. And along with the books and furniture I inherited from her a number of brittle plastic boxes that contained her writings. She’s already written a book, based on the life of John Keats. She was a Keats scholar. She taught at the university in the city where I grew up. And so I had her papers, the notebooks she kept about her studies and about her life, but for a long time, because her handwriting was so atrocious, I never really read these notebooks. It was too daunting. Until at some point I was given a residency in New Hampshire, at the MacDowell Colony—although they don’t use the word colony anymore—and I steeled myself, sitting down every day and deciphering or trying to decipher her words. At first it was almost impossible, but after a while I came to know her handwriting style and was able to make sense of what she was writing about. Not only make sense. I was touched. She was trying to be, and writing about the struggle of trying to be, at the heartache and love, and from these notebooks I collected a number of quotations, and using them as a framework I began writing. I didn’t know if I was writing about her or writing about myself. And I didn’t care. When her notes didn’t fully explain her life or detail her feelings, I used events and people that were tangential to her life, painters she admired or people she’d told me had inspired her. And what I came up with wasn’t an objective portrait of her because it was also a portrait of me, a kind of double exposure; her and me together in one image.

RG: To pass the test I have to be what I never wanted to be, to take my turn in a story that isn’t mine, and that’s what stories do, they start out going in one direction and then they veer off, and part of being in a story is letting it go, letting the story take you to the place you didn’t even know existed but there you are, and yes, there’s always a choice, but standing in what had become a circle, the choices I had boiled down to running away or doing what they were asking me to do, not telling me, but it was clear what they wanted.

How much do you impose yourself on your writing and what part is left to chaos?

JH: At this point, for me, it all seems like chaos. Not a wild chaos; a slightly calm and ordered chaos, a chaos that, because it’s chaos, has some holes, some places where I can fit myself in. And if, by chaos, you mean out of control, then really it’s only chaos because we want to maintain control. By relinquishing control the chaos calms down, gets slightly peaceful, and I find that pleasant. And thinking about the idea of “calm chaos” makes me think that in all of these questions I’m saying that many disparate things can happen at the same time, that divergent events can coexist, that different personalities can coexist, that different ways of thinking can dissolve into each other and when they come out, or come up for air…

RG: Where are you heading?

JH: Now, having written the book, where I’m heading, at least in my mind and in my desire, is toward performance. The pieces were written with the ear in mind. I meant them to be read aloud and personally, I love to read them to people, to talk them out and think them out. So where I’m heading? Performance. I started my writing life as a performer, on a stage or in a club and telling stories. The stories then were not so dissimilar to the ones I’m writing now, and I’d like it if I could perform them more. And also, speak them more. None of my books has even been made into an audio book. Which for me is sad. It’s a dream of mine, to give people a chance to ride the subway or drive in a car or sit in a chair and hear the stories/essays being read aloud. How does one get this to happen? I don’t know, but I’d like to be able to tell the story of the book I’m writing now so that people can hear it as well as read it. That’s the dream, anyway. Thank you so much for asking me these questions.