Antioch looked good, good, good. Red crosses on white banners blazed over the citadel, framed by the smoke of smoldering pyres and the grapevines grown fat with dusty fruit on the hills outside the city—and all this on a cool summer afternoon. Sir Godfrey of Handover resolved to make note of this fine moment in his journal of gratitude as soon as the Lord’s work was accomplished.

“It all looks so good, doesn’t it, Clive?”

The skull Sir Godfrey held nodded half-heartedly, then turned southward toward Jerusalem.

“I know, I know,” said the knight. “Patience, dear friend.”

Clive, of course, was eager for the Resurrection, which required (of course) the coming of the Kingdom of Heaven, which undoubtedly required the return of Jerusalem to the hands of the Saints and the reunification of many-schismed Christendom—a goal which seemed, at present, to require a certain amount of marauding.

“Soon enough, sweet one,” Sir Godfrey said, cradling Clive as he torched a fresh corner of the little Muslim village. People were screaming and hurrying about as the Kingdom stretched southward, fire licking at the fields of wheat.

It would all be very interesting—the Resurrection—because Sir Godfrey and his serf Clive had parted on uncertain terms the previous year. Clive deserted the green hills of Handover to go reaving in the Holy Land with the other peasants, pitchfork in hand. Another lord might be furious, but Sir Godfrey waved him on; he would miss the old peasant, but who could argue with a summons from the Almighty? Besides, Godfrey and Clive shared a special bond. When Godfrey was young, Clive had led the little lord’s pony carefully around the woods, and when Godfrey grew older, Clive had polished his armor. The serf was almost family to Godfrey. Could a more intimate friendship exist between peasant and knight? But from the high road out of town, Clive had bellowed something back at Sir Godfrey, something to the tune of “the meek shall inherit the Earth,” as if revealing some long-held resentment toward his feudal lord.

In the moment of Resurrection, Godfrey would say to his serf Here I am, Clive, I’ve brought thee back, having conquered the Holy Land. Did I not do right by thee? Was I not a good lord after all? And Clive, of course, would agree.

The men were galloping this way and that, clanking in their polished heavy plate, singing songs of worship. Baldwin the Hermit led them, swinging his mighty mace.

Refiner’s fire! Baldwin sang. My heart’s one desire…

Is to be holy, the rest of the men joined in, set apart for Thee, Lord…

Baldwin: I choose to be holy, set apart for Thee, my Master…

All: Ready to do Thy will…

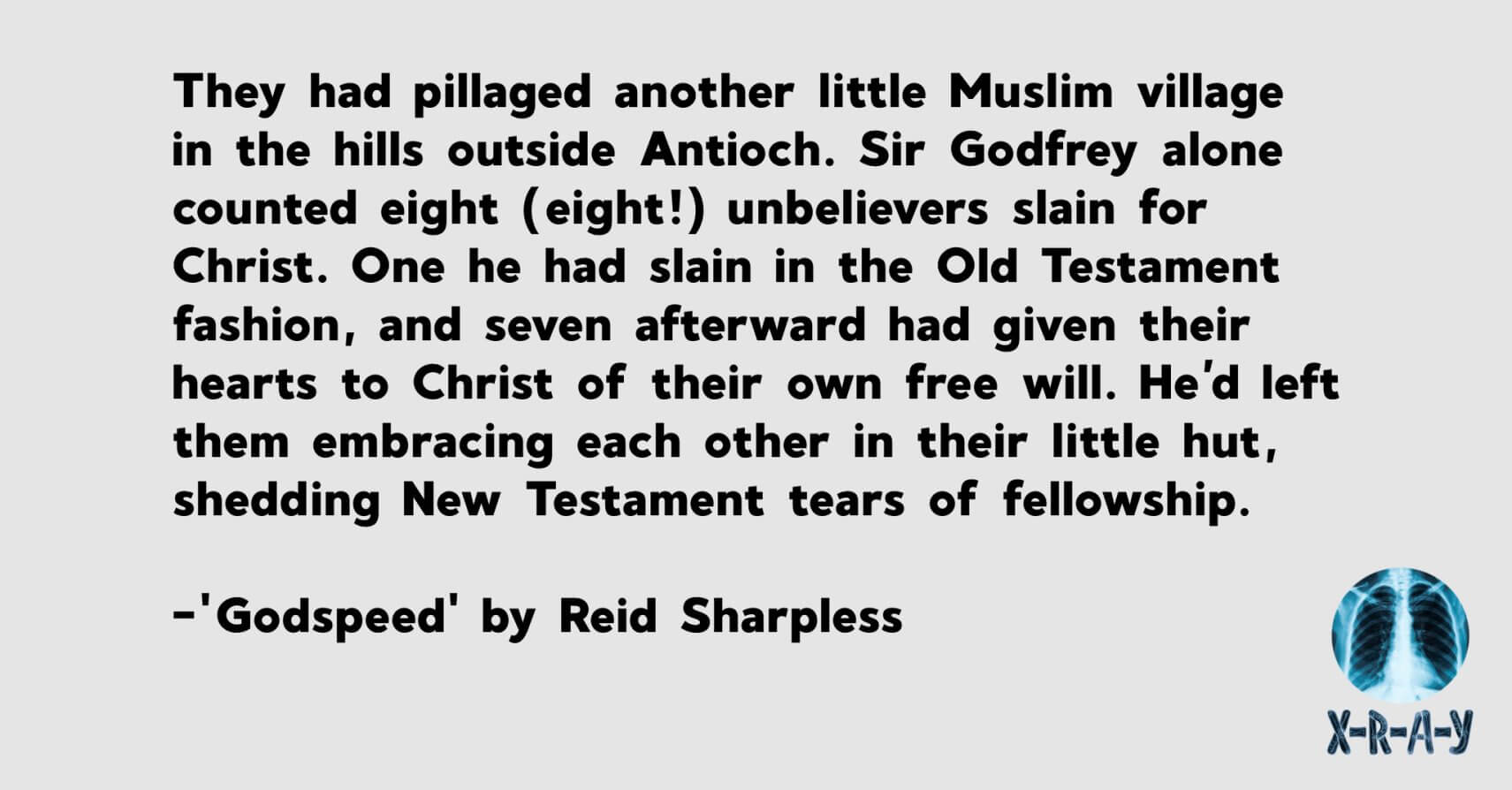

It was yet another miracle! They had pillaged another little Muslim village in the hills outside Antioch. Sir Godfrey alone counted eight (eight!) unbelievers slain for Christ. One he had slain in the Old Testament fashion, and seven afterward had given their hearts to Christ of their own free will. He’d left them embracing each other in their little hut, shedding New Testament tears of fellowship. And just when all had grown quiet, several dozen sheep and goats burst from the burning stable and streamed toward the crusaders like the animals led by the Lord Himself onto Noah’s Ark! A miracle that, on this day of bloody victory, their hearts and bellies should be so full.

Such miracles were occurring with great regularity as the noble crusaders approached Jerusalem. With each step deeper into the Holy Land, the scriptures became more undeniably real. What in gray Europe had existed as invisible movements and whispers of experience—a trembling heart, a pang of guilt, blind inner brushes with the Holy Spirit—had in Asia Minor become obvious enough for even the dim-witted to see. Angels (angels!) had been sighted as bright glints of light, stars exploding in the vision of knights like sparks of struck iron. An image of the Virgin Mary had been reported in the sand, and the faces of apostles were visible in the clouds during battle. The crusaders had marched twelve circles around the walls of Nicaea, blowing trumpets and singing songs of worship, and behold, the hearts of the Turks within had softened; the gates of the city were opened to them, even while the siege engines stood only half-erect outside. And earlier that very day, as they battled the Turks for Antioch, the Lord had brought a cool breeze over the mayhem to dry the sweat from their brows as they did His work. Miracles! It was all so bittersweet, knowing that once they raised their flags over Jerusalem, history would come to an end. Life was just beginning to feel right.

The men had ridden their horses into thick lathers and sung their voices ragged. Baldwin the Hermit directed the knights to a fork in the southern road, where princes were taking seats, visors raised, with cool cups of watered wine in their hands as their squires doffed their armor and the camp followers butchered the pillaged livestock.

“In the next life, Clive, I shall have thee serve as my squire,” said Godfrey.

The skull stared off into the middle-distance.

Godfrey dismounted and set out in search of his nephew, Edfred, that they might doff each other’s plate. Already, princes and knights were showing each other what baubles, relics, and bones of significance they had gained in the sack of the citadel. Sir Gnut had found a finger bone of John the Baptist. Baron Valclaw found a stained silken glove belonging to Paul of Tarsus. Duke Gedward found the ear of Malchus (severed by the Apostle Peter) perfectly preserved in a jar of pitch, as fresh as if it had been dismembered that very day. And Baldwin the Hermit found the iron tip of the lance that had pierced Christ’s side—this discovery had inflamed Christian hearts with such zeal that the men then rode out beyond the walls of Antioch and, in a righteous frenzy, smashed the Muslim counterattack. These relics were the most celebrated to-date, but surely Jerusalem held more.

“What have ye there?” said Sir Gnut, eyeing Clive’s skull in the crook of Godfrey’s arm. “The skull of John the Baptist?”

“Nay sir, ‘tis my dear serf, Clive, who came here on the Peasants’ Crusade. He met his end outside Nicaea, and now I ride to avenge—”

But Sir Gnut had already left, searching out other pieces of the Baptist. Godfrey didn’t blame him: the relics were a godsend. Mere days ago, Godfrey’s heart had been baffled by doubt of his holy purpose. But hearing of this, Baldwin the Hermit came to him, and from his saddlebag he produced a sack of bones safekept for Godfrey—the bones of Clive.

“Thy friend is with the Lord now,” Baldwin had said, handing over a femur, “but his bones cry out for justice!”

Godfrey’s strength surged within him at the outcry of Clive’s bones. For the bones of Clive he’d fought valiantly in Antioch, and would now fight on to Jerusalem. If only Baldwin the Hermit could give some fortifying relic to Edfred, whose strength was waning.

Sir Godfrey found his nephew sulking at the edge of camp, looking back over the smoldering city. Edfred, of course, had joined the Holy War to assure himself of his salvation. But the boy had not once bloodied his sword in combat. Instead he’d become enamored with a group of young Muslims—a girl who washed his feet with her hair and several young men who called him friend and toured him about the city as it was being pillaged. Only at lunchtime, as Edfred sampled the delicious foods of the market square, Sir Gnut slew his friends.

“I’m sorry,” Sir Gnut had said to Edfred in the clamor of battle, “I didn’t know they were yours.”

Edfred muttered forgiveness and turned away to shield his fragile heart. But around the wine barrels there still circulated boasts and rumors of Sir Gnut’s various conquests in the sacking of the city.

“Come, nephew,” Godfrey said, placing his hand on the boy’s shoulder. “Thou knowest we kill only in kindness.”

The boy shrugged off his uncle’s hand.

“Would that I had never come here,” he said. “I have not lived a life of great sin requiring such terrible acts of atonement.”

“Here,” Godfrey said, “hold Clive.”

Godfrey gave Edfred the skull, twisted the boy around by his shoulders, and began unstrapping his gorget.

“By the time thou art mine own age, thine heart wilt be so heavy laden with doubt that every night thou wilt lie awake in torment.”

Edfred was quiet. A redness dappled his pale neck.

“When our work here is done,” Godfrey said, “thou shalt never know a heavy heart.”

“Is this even Clive?” Edfred asked, turning the skull over in his hands.

Clive looked Edfred squarely in the eye, but feeling a great revulsion for the boy’s softness, quickly cast his gaze downward.

Godfrey unbuckled the rest of the boy’s plate and wrested the skull from his hands. Edfred stood, wriggled himself out of his armor, and turned to doff his uncle’s plate.

“Of course it is Clive,” Godfrey said. “See? Here, the place where his nose once was, the place where—”

Trumpets sounded. Baldwin the Hermit was raising his banners around the barrels of wine.

“Ye tired and ye weary,” he shouted, “we stand at a crossroads. We can press on to Tripoli…”

The knights raised the tired huzzah of men who have taken what they wanted yet are met with new things worth wanting.

“…or we may leave Tripoli to the laggards and instead fortify ourselves for the crown jewel, Jerusalem.”

The men were silent in their consideration; surely they would have all the time they needed for relaxation once Eternity began.

“Thy blades are sharp and armor gleaming, but hast thou taken the whetstone to thy Sword of the Spirit? Hast thou oiled thy Belt of Truth? Hast thou polished thy Shield of Faith, thy Breastplate of Righteousness, thine Helm of Salvation, and thy Sabatons of Peace?”

Edfred ceased his fumbling with Godfrey’s leather straps to listen closer to the words of the Hermit.

“I know a place that floweth with milk and honey,” Baldwin continued. “There we may purify our hearts, so that in the final moment of the broken world, Christ might say to each of us: today thou wilt join me in paradise.”

At this, all the men raised a joyous Deus vult, and Edfred raised his boyish voice with them in cracking assent. Yet Godfrey could hear the bones of Clive protesting from his saddlebags.

“Not south?” said Sir Gnut, lifting his gaze from his work on a nearby sycamore. He and his fellow northmen had grown fond of removing teeth from the infidel and driving them gently into trees with the flats of their blades and butts of their axes to mark their path southward.

“South-southwest,” said Baldwin. “And only until Jerusalem is laid under siege.”

“South-southwest is south enough for us,” said Sir Gnut. His northmen grunted amiably and returned to their decoration.

Sir Godfrey thought to protest, to offer some counterpoint—he had stamina to spare and was eager to claim more lives for the Kingdom—but Edfred was now proclaiming desperately with the others that they should go at once to the place Baldwin spoke of, where they might shine their spiritual armor. Out of pity for the boy, Godfrey spoke not a word against it.

“Patience, sweet one,” he said to Clive. “This delays thy Resurrection for but a little while. What is one short detour in the face of Eternity?”

…

Baldwin the Hermit led several hundred knights toward the sea. They climbed Mount Carmel’s gentle, chalky slopes—the northmen marking the occasional laurel, oak, and olive tree—and from there they began the descent to the glaucous coast. Baldwin pointed to a cairn.

“There is the altar on which the prophet Elijah called down hungry flames from Heaven and shamed the priests of Baal,” he said. “And there,” he pointed, “is the cave where the prophet Elisha hid after summoning the bears from the wilderness to maul the forty-two young men who ridiculed his baldness.”

The knights took stones from both places, and when they had filled their satchels and saddlebags the cairn was gone and the rocky hollow was picked clean, swept of all its precious dust.

“And here we are,” said Baldwin, sweeping his hand toward the sea.

A yellowed limestone keep stood in bright relief against the Mediterranean. Even to Godfrey’s eyes it was a relief. Men could be seen playing lawn games within the fortifications. A small harbor sheltered ships from Christian nations, and the beaches and dunes all around were festooned with palm trees and dotted with small wooden villas dedicated to spiritual replenishment. The knights dismounted and ran toward it as children might.

…

Godfrey lounged on the beach with the bones of Clive, shaded by a large parasol made of palm fronds. The warhorses grazed just over the dunes, while Baldwin and the men frolicked in the waves, riding gentle swells on bits of flotsam. Friendless Edfred stood apart in ankle-deep water, gazing northward along the coastline. And Godfrey lounged there, perfectly content in the sand under that damned fine parasol.

Antioch looked good, good, good, he wrote in his journal of gratitude. Thank you.

“What would thy betrothed, the fair Lady Godwina, say if she could see thee now?” Clive asked, attempting to spur the knight on from his quiet repose.

She’d say what she always said, Godfrey knew. Remember thy code of chivalry, keep the Beatitudes close to thine heart, turn always the other cheek, bear into perpetuity the Ten Commandments graven on thy mind, and every day write of three things for which thou art grateful. She’d said it even at the moment of farewell, as she tied her red ribbon around his arm.

“Thou art a thorn in my side, Clive,” said the knight.

But Clive awaited an earnest answer, and the silence weighed on Godfrey’s heart.

“She’d remind me: thou shalt not murder.” Godfrey began. “To one who strikes thee on one cheek, turn to him the other also. Thou shalt not recoil before thine enemy. Blessed are the merciful, for they shall be shown mercy. Thou shalt make war upon the infidel without cessation and without mercy. Blessed are the peacemakers, for they shall be called children of God. Whosoever joins in Holy War shall receive absolution for his life of sin. And she’d remind me to be grateful.”

The skull waited.

“I am grateful for the ocean, for the palm trees, and for thee, Clive.”

“To be a knight is to walk a very straight and narrow path, but thou dost make it look easy,” said Clive, impressed.

Satisfied, Godfrey leaned back against his saddlebag until one of Clive’s bones snapped.

The crusaders were still out there in the surf, a new excitement now about them. Sir Gnut had been caught in the undertow and swept out to sea, but the Lord had called forth leviathans of the deep, which found him, buoyed him up to the water’s surface, and spirited him back to the safety of the shallows, and now all the blessed beasts frolicked playfully with the knights.

A glint to the north caught Godfrey’s eye. It was an angel. No, it was a new star. Edfred was stumbling in the surf beneath it. No, it was a sword, slicing through the firmament. Edfred had hurled his longsword into the sea.

…

Clive watched the men’s armor rusting in the salt breeze. Knicks and scrapes on the steel blossomed into crimson florets until the whole pile was awash in color. Then one morning, peasant women with children slung close to their breasts came and placed the armor in barrels with sand, and spent the day rolling them to and fro. When the armor came out it was mirror-bright, good as new.

…

On the road to Jerusalem, Baldwin the Hermit preached to the men who followed him. Before all this crusading business, everyone assumed the speed of God to be quite fast. Faster than a sprinting man, faster than birds, faster even than wind. But with each passing year—even one thousand years—the Lord did not reap His harvest from the world. But Baldwin had finally realized: the speed of God was actually quite slow. Slower than ants, earthworms, and tree roots, more patient than rocks. It was slow because the Lord’s plan required noble, Christian hearts to speed along the end of all this misery. Of course! Their fathers and fathers’ fathers had waited a thousand years for Christ’s return, when they could have marched over to the Holy Land and brought on the Second Coming in a mere five!

Red is such a pleasing color, Godfrey decided, as he charged the city’s northern gate. It was miraculous what red could wash away, leaving behind only pure white. The red of Christ’s blood. The red of communion wine. The red that soaked the horses’ ankles in the market square. Godfrey felt his heart lighten with every swing of his sword. He had always been a selfish person. A self-centered, sinful wretch. Having a self at all was an excruciating torment to Godfrey, a stain upon his soul. But with every new vermillion gash, he felt a measure less selfish. By the time he stood panting on the Temple Mount overlooking the city, his heart was white as snow. Clive smiled from the crook of Godfrey’s arm, and the two of them stood there, waiting for the Lord to take His broken world and make it great again.

Only once the men had raised their banners over Jerusalem, trashed its streets and slaughtered its people, nothing happened. They inspected their fallen foes. The Mark of the Beast did not appear on any of their foreheads, nor did the knights find signs or symbols of significance anywhere else; only the red-on-white crosses emblazoned on their own banners and clothes. They’d stormed the very capital of the Holy Land, yet Christ did not come down from His high seat to walk among them, to make the broken world new again.

“And then what happened?” Clive asked. The way he posed it seemed unkind.

Then the knights found themselves quietly wandering the scorched city, inspecting its walls and temples, drifting through places where all those Biblical people had lived and done things and died and risen again. Sir Gnut found the Garden of Gethsemane. Baron Valclaw stood in the Shadow of the Valley of Death. Duke Gedward found Golgotha, and nearby, Baldwin the Hermit laid for three hours within the Holy Sepulcher, where Christ had laid for three days.

Godfrey and Clive climbed a bluff above the city, the deep red clay sucking at his boots. They found the potter’s field purchased with the thirty pieces of silver for which Judas betrayed Christ, where Judas was said to have either hung himself or burst explosively in regret. A solitary olive tree stood within it, a rotten rope hanging from its thickest branch.

Godfrey sat beneath the tree. Edfred would have liked that part—sitting under the tree. From there, Jerusalem looked even better than Antioch had looked. But the boy was on a ship bound for Handover with neither sword nor relic to his name.

“And then what happened?”

“Then nothing,” Godfrey said. Nothing had happened. The bones of Clive did not knit themselves together with new sinew and muscle. All the dead saints remained in the ground. Fallen crusaders lay there purpled on the streets. The sky did not tear asunder. There was no clap of thunder, and hardly a trumpet was heard. The only thing that happened, really, was a collective remembering of the words of Christ: the Kingdom of God was within them, after all. From this the men forged new pieces of spiritual armor, something made of chainmail, surely, which covered all remaining chinks and vulnerabilities in the armor of God.

All the armor had become quite heavy, however. Godfrey could not rise. He opened his journal of gratitude to write, but wept instead. The ground soaked up his noble tears.

I’m grateful for the speed of sprinting men.

I’m grateful for the speed of birds.

I’m grateful for the speed of wind.

He closed the book.

“Tell me, Clive, am I a good person?”

The skull nodded blankly, a mask.

“So I am a good person? A good man? Answer me now.”

“Of course,” a womanish voice said.

The skull dropped to the ground.

“Who art thou?” Godfrey whispered.

But the headbone rolled to a stop, discharged of all magic.

…

The knight unslung his satchel and dumped a pile of bones under the tree. Above, the rope swung limply from the bough. Bark had grown over it, wood constricted and bulging where it had been fastened long ago. He wanted that rope. He hacked the sapless branch from the trunk and hefted it over his shoulder. Then he carried it back down to the city and paraded it in front of his friends, who congratulated him.