“I think we ought to read only the kind of books that wound or stab us. If the book we’re reading doesn’t wake us up with a blow to the head, what are we reading for? So that it will make us happy, as you write? Good Lord, we would be happy precisely if we had no books, and the kind of books that make us happy are the kind we could write ourselves if we had to. But we need books that affect us like a disaster, that grieve us deeply, like the death of someone we loved more than ourselves, like being banished into forests far from everyone, like a suicide. A book must be the axe for the frozen sea within us. That is my belief.”

“I think we ought to read only the kind of books that wound or stab us. If the book we’re reading doesn’t wake us up with a blow to the head, what are we reading for? So that it will make us happy, as you write? Good Lord, we would be happy precisely if we had no books, and the kind of books that make us happy are the kind we could write ourselves if we had to. But we need books that affect us like a disaster, that grieve us deeply, like the death of someone we loved more than ourselves, like being banished into forests far from everyone, like a suicide. A book must be the axe for the frozen sea within us. That is my belief.”

― Franz Kafka

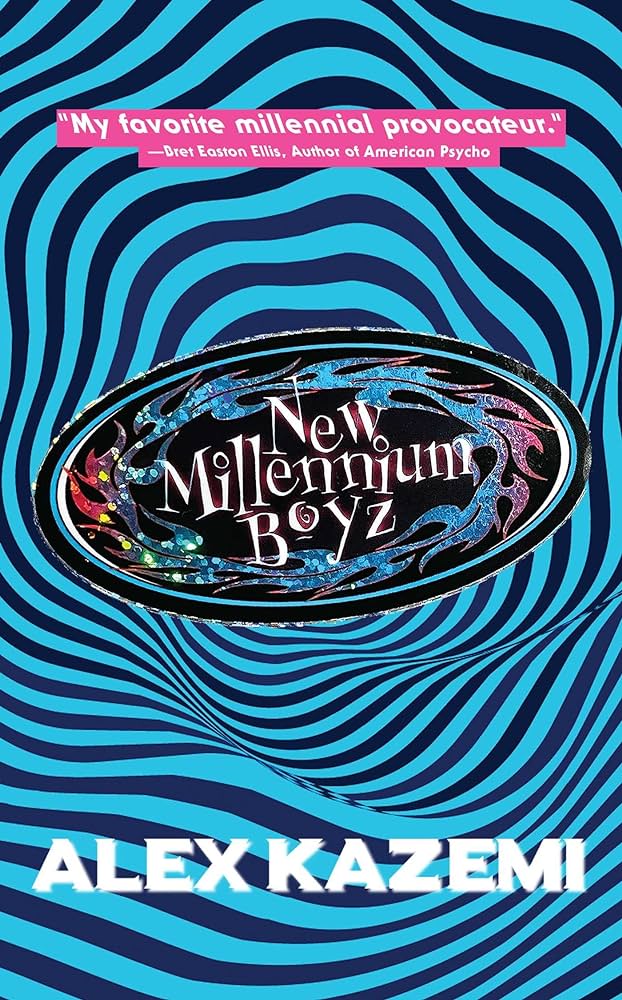

When reading Alex Kazemi’s New Millennium Boyz (Permuted Press, 2023) the above quote from Franz Kafka repeatedly invaded my mind. Kafka’s flair for the dramatic doesn’t overshadow the points he’s making. Kazemi’s novel transports us back to when pre-millennial tension reached its crescendo, announcing the turn into a new century. With themes such as bullying, self-harm, cruelty, drug misuse and abuse, school shooters, suicide, and discrimination, the book forensically pulls apart disaffected youth and reconstructs it in bruised hindsight. Kazemi satirically inflates the media language of alienated adolescence and repackages it for whatever iteration of post-postmodernism we are currently attempting to compute.

I feel like I should wear a t-shirt saying whatever you think of the ACTUAL BOOK… The book has ruffled feathers on many levels; some view it as a lame stain on the modern publishing scene, and others claim it as their own to fit an agenda. Teenage angst has paid off well, now we’re bored and old. I spoke with Alex about the book and what it is like to be at the center of a self-imposed shitstorm. A book must be the axe for the frozen sea within us.

Rebecca Gransden: For the uninitiated, can you talk about Yours Truly, Brad Sela and the genesis of New Millennium Boyz?

Alex Kazemi: Yours Truly, Brad Sela was a project that started when I was 17 years old. I was really just putting together ideas from thoughts and notes I started taking: on my phone, laptop, notebooks. I was exploring, but as an adult, I understand the novel was in an extreme early gestation period. I mean, the general thematic idea, or outline of themes that fascinated me, were very clear in the early drafts but the reason the book took so long was because I was very much trying to compete with myself, and create a style/vision that felt true to the essence. Musicians can say “I want to make an album that sounds like 1990s trip-hop” but it’s going to take time to figure out how that sound cultivates and what it ends up representing for you as an artist.

Yours Truly, Brad Sela went viral when I was 17 on Tumblr. I just uploaded the first 50 pages and teenagers were losing their minds, they felt they related so much to the characters and it was a bit of a “find the others”-type mission. I wanted to feel less alone, and I still kind of stand by that mission as an adult.

RG: Many labels can be applied to the central focus of the book, Brad. As his creator, how do you describe him?

AK: Brad, to me, is someone who is not supposed to be a narrator. He’s the guy in your Y2K senior photo who is in a Blink-182 tour shirt, he’s good-looking, he hasn’t had many struggles. It doesn’t feel like anyone would want to read a novel written by a guy who whips his friends with his wallet-chain, but that’s why I wrote him. I’m fascinated by breaking the rules in literature, and as I’ve wanted to take this “extreme teen sleaze” to the umpteenth degree, I thought he’d be perfect.

I would describe him as someone who is extremely anxious about how people perceive him. He’s constantly thinking of if he’s masculine enough, if he’s honest enough. He’s also someone who is extremely bored and anesthetized by 1990s MTV capitalist consumerism culture. He wants to unlock darkness, he’s craving danger, he wants intensity, but he’s also a little boy deep inside and he knows this, so he has to manage carrying the shame of not being “adult enough,” he’s totally in limbo…

RG: Within certain artistic circles there is a resurgence of interest in ’90s culture. A type of fetishisation has emerged to accompany that. What do you see as behind this and how do you view your part in it?

AK: God, I think it’s exhausting. It’s ridiculous. It’s because human beings are so compulsive with social media, we’ve created this nauseating feedback loop culture. You know, the whole “20-year cycle” of nostalgia. I mean yeah, teenagers were wearing jeans from the ’70s and getting into ’70s music [in the 90s], but the internet is an endless magazine. The algorithms want us to be creating and producing the same work, so we are all in a totalitarian cookie-cutter regime.

New Millennium Boyz plays a role in nostalgia culture as a trapdoor. It’s not what you think it is. It is making fun of the reader’s interest in the novel right from the opening page. I hope I don’t contribute to nostalgia culture. The novel is anti-nostalgia and I’m quite cruel about it.

RG: With all levels of culture scrutinized in political terms, do you invite the inevitable politicization of your work?

AK: I invite the controversy and politicization because a shocked reaction to this work really just makes my point about why I wrote this novel. It’s all so obvious, and I’m bored to death. I’m sure some right-wing conservative sees New Millennium Boyz as a middle-finger to the nonexistent “culture war,” but also, I can see a liberal feminist seeing the book as an excuse for a white man to disguise “hateful tirades” as literature. It’s all so ridiculous. You have to laugh at this point.

RG: How do you view the concept of phonyism, of being a sellout, both with regard to how your characters are impacted by it, and in a wider context, comparing the turn of the millennium to now?

AK: Being a sell-out, and “authenticity wars,” is a very Gen X ideology. I can understand 20 years ago, when a “monoculture” used to exist and overground mainstream/underground indie used to be so distinguishable, why those values might matter. But I really think in the end it’s all a narcissistic fantasy. “I’m more pure than you, I’m more real than you because I have less of an audience.” It’s child’s play. Foolishness.

I’m a pop artist, I was born a sellout. I’ve always been about trying to televise dangerous ideas to the masses or bringing underground ideas to a wider audience. I come from the Madonna school of thought.

RG: It’s a cliché, but Woodstock ’99 was the Nineties’ Altamont, the moment the dream of the inmates taking over the asylum was dashed by Fred Durst demonically ushering in the return to dominance of bro culture. There is a frustration that no real artistic movement of wide significance has arisen since (debatable, but I think largely true), but I see this as the banging of heads against a fantasy brick wall, as there is no cultural monolith to take over now. In a world where Balkanization dominates, how do you view the artist’s place?

AK: I think about this a lot, Rebecca. I mean, I would hope the artist’s place is to use the information age to access their audience and create some kind of resonance, or identification in a consumer who feels like they’ve been waiting for the art that you’ve created. I do think every artist has their own place, own role, but without a simple monoculture to infiltrate…like, there is no more “getting on MTV.” You now get on your friend’s Instagram feed, and maybe some similar algorithms. Everyone is a novelist. Everyone is a photographer. Everyone is an actor. Everyone is a star. When everyone is doing something, does the occupation lose value? Is total oversaturation dangerous? I wonder.

RG: We are past the age where all publicity is good publicity. How do you view provocation in the modern scene and do you expect cynicism in response to the book? I have to ask: are you baiting online discourse?

AK: Yes, absolutely. I’m baiting online discourse. The indie scene is so comfortable amongst hierarchies, cliques, filter-bubbles and a general nauseating obsession with being “cool” or “alternative.” I think particularly what grosses me out is all the masqueraded competition and pretending to be friends with each other. Nothing is real or genuine in those indie scenes. The book’s marketing campaign’s job was to piss those exact people off, shake them up, have them be offended, outraged. “Who is this delusional author who is on an indie press I’ve never heard of, who has the entire Gen X literature glitterati backing him up, and who are his marketing team who are so persistent and annoying?” It’s called publicity, baby. Everyone in the indie scene really exposed a lot of their fragile egos and insecurities in the way they reacted to NMB and it was quite delicious to watch.

RG: I’m firmly of the belief that an artist’s only responsibility is irresponsibility, with regard to their work. The book features a comprehensive content warning. Do you have an opinion on responsibility when it comes to New Millennium Boyz?

AK: Bret Easton Ellis told me it was “badass” when I got the call Simon and Schuster wanted a content warning. I’m not responsible if anyone internalizes fictional work as reality; that is something for a psychiatrist or psychologist. These ideas are not new. I would argue—these ideas are not even transgressive.

RG: Your characters experience very normal chaotic growing pains, and you focus particularly on the challenges of being a teenage boy. One aspect that stood out to me is that of the issue of the private and the public. Privacy becomes particularly important at that age, from having a room of your own to claiming greater freedom outside of the family unit. There is no privacy in small-town living, at least in the era presented in New Millennium Boyz. For those susceptible to external validation, which most teenagers are, the invasion of privacy offered by the online world offers a type of attention which seems remote, distanced from immediate consequence. This generation is also acclimatized to being surveilled, and CCTV footage is part of their entertainment and a potential source for their own notoriety. When compared to now, this era seems almost quaint, as online culture and the virtual town square has accelerated and amplified the pursuit of external validation to a point where it has become normalized. How did you go about incorporating these themes into the novel?

AK: I agree with you 100%. Y2K was the true televised death of privacy and it was the first time people really started to feel the shift of regular people starting to enter “the spotlight.” You could go on a message board at 10am, write an opinion about Marilyn Manson, come home to 30 replies, feel a false sense of validation and contribution, and then this type of performing could be extended into making your own webpages, answering Q&As about yourself.

The anxiety the novel speaks about led me to studying the Paris Hilton scandal, when private videos of her were uploaded online and people were able to make an entire website directory of her private journals, clips and photographs. The digital world is designed to betray you, and no one can be trusted. Brad goes through a sense of anxiety of wanting the video cameras to be gone and off, but he also uses the camera for sexual arousal. He knows what he is doing on these tapes: he wants scandalous things taped, but he doesn’t want anyone to find out about them. He wants privacy. This is the exact opposite of today’s teenagers. Teenagers want to televise their scandalous moments on Snapchat and TikTok and they want to shock an audience, to garner a following. Everything is currency.

RG: In many ways the novel pinpoints a time of spiritual bankruptcy and anomie. The normal obnoxiousness of being a horny teenage boy is left to run riot in a sensationalistic world. These are children of divorce coming of age, and, whatever the reason, they are ill-equipped to navigate a high-speed society and its excesses. How did you want to approach the representation of teenagehood in the novel?

AK: I knew my characters were Xillennial latchkey kids and I knew I wanted to capture the sense of disconnect the parents felt to their kids, but also the delusions they induced into their children. “Be good, be smart, be perfect.” I wanted to depict a dirtier, sleazier, but also surrealistic portrait of American youth in a period where the “teenager” was so fetishized, as seen in all of the teen movies associated with the millennium. It’s almost like, “How do we take the boys from American Pie and put them in a Larry Clark film?”

RG: These kids are branded, and overloaded with corporatism. Authenticity becomes a spending choice; the promise of glamor and success can be purchased. You saturate the text with brands, TV shows, music. How much research did you undertake for the book, and what form did it take?

AK: The saturation is supposed to induce nausea into the viewer. It’s supposed to make them relive the first feeling of when they saw a candy commercial as a child and felt hypnotized and hooked. I chose to do this because the Y2K monoculture was the last era of teenage brainwash and I wanted to spam the readers with all the falsehoods of corporate America to then juxtapose the more real, authentic, scarier moments.

The research took a decade, if you want me to be honest. I was in such a buffering mode of continuously finding obscure references in university library databases, home videos, website archives, tapes I bought off eBay, photo albums. I really exhausted every resource I could because I wanted to feel like you were reading something written back then, almost like if New Millennium Boyz came out in 2001. That was what I was going for. And of course, I do think Bret would agree, the book co-exists with the universe of Glamorama.

RG: MTV is an obsession, and many of your characters’ lives revolve around it. The intensity of the fixation is overwhelming. Did you have similar obsessions growing up, and, if so, does your experience feed into the book?

AK: As a child, MTV was all I could think about. I was obsessed with pop culture, I found it to be the most exciting, exhilarating part of my life. Pop culture was an escape from the horrors of feeling like I couldn’t connect with anyone or anything, and like it is for my characters, it was a way for me to attempt to form bonds, or make conversation, or to integrate myself into the world.

As I got older and became a teenager, I saw how grim all the marketing was and how this was all a ploy, and I snapped out of my trance. I guess the book is a bit of an angry response, me wanting to unveil what was lurking beneath those glossy surfaces.

RG: Is the book an act of disruption?

AK: I think New Millennium Boyz disrupted the consensus of the indie world. Everyone wishes I played their game their way. and I wrote ten poems for Hobart and was friends with an Expat Press author and my deal was announced on Publisher’s Marketplace. I do think the book is disruptive for most readers, it’s very draining and exhausting. Some people feel that going through the journey of the novel is rewarding and other people just feel like it was an absolute waste of time.

RG: Your previous work has addressed magick belief and practice. Is there magical intention embedded in the book, and if so, do you have a specific objective when it comes to how that could manifest?

AK: A Kabbalist never shares his secrets, but yes, magick and a specific intention were imbued into the creation of the novel, and I think we’ve seen it unfold.

RG: It could be argued we exist in a post-spectacle society, where value is placed on the spectacle of ourselves and mirrored back to us. Then, any external spectacle’s worth is measured by its relevance in relation to personal image. In a literary sense, I see this demonstrated by the inflation of the quality of relatability above other aspects. Curiosity is deadened towards literature with views and experiences outside, or opposed to, those that immediately reflect a particular point of view, and violent rejection often follows. In the age of New Millennium Boyz we’d just change the channel, but now there’s a hunger to take the channel off the air. I’d be disturbed to see it, but I do fear there are some who would want real world punishment to come your way for some of the themes you address and the language you use. Was public reaction a consideration when putting the original concept for the novel together?

AK: I think you are right. I think certain political extremists could view this book as an act of violence, all for what you are saying, a contribution to their own spectacle. People could exploit the book to perpetuate their own propaganda. I think my publisher thought more about public reaction because I kind of was attempting to say the world is too desensitized to care about a book like this.

RG: I don’t have a mobile phone, and it is becoming increasingly difficult to function on a societal level without one. You position the novel at a time where technology is fervently stoking its own myth—with the Y2K bug imminent, that moniker itself an instinct to apply the organic and biological to the digital, to the machine. A major theme I took away from the book is how biology has turned us against ourselves and led us unconsciously to the age of the algorithm. To the perpetually online, the eventual endpoint of this is a form of psychotic dialogue with a self only educated in the language of itself. Mise en abyme infinitely mirrored. Why did you select the change of the millennium as the right time to set the book?

AK: I agree with you. Thank god you don’t have a mobile phone!

I chose Y2K to explore the themes you’ve mentioned because it was the birth, the seed of all the hyperreal themes and issues of today’s narcissistic, technology-driven society. Everything was just on the cusp, everything was about to arrive but still it was in such infancy that a monoculture still existed, not everyone was totally brainwashed. I mean, some people in this era didn’t even have cable or the internet! The choice to be in The Matrix or to not be in The Matrix was less about survival and coercion. It was about free will. I think as the 2000s progressed, technology replaced religion and we started to believe that what we search, what we look at, is what reality is. Humans started to really disconnect from one another as the late 2000s arrived.

RG: For your characters, social image becomes conflated with media image. To them the sensational imagery provided by the pervading culture becomes addictive, a rush. In time this exhibits itself in the adoption of the vernacular and formats of the media they consume, a media which signifies the seductive and transcendent promise of fame, success and validation. They gradually immerse themselves in the language of tv and films, as a way to frame their reality, and once on this path, there is a sense that the characters are giving themselves over to a type of predestination, unconsciously living out the illusory narratives propagated by mass mainstream culture, or at least trapped in a dysfunctional dialogue with a culture running out of control. The temptation to blame art and culture for heinous acts is an old one, from the video nasty campaign and fundamentalist religious calls for censorship of the ’80s and ’90s to the more diffuse arguments from across the political spectrum currently. Do you have an opinion on this, or is something deeper at play in New Millennium Boyz?

AK: Nothing is deeper at play. You figured it out. That is exactly what is happening. You’ve left me speechless.

RG: I think it fair to say the novel comes after the Literary Brat Pack authors. Would you like to run in a pack or are you more into lone-wolfing it?

AK: I guess I’m destined to be a lone-wolf, but also, Rebecca, a Literary Brat Pack is not possible in this era. No one reads magazines, and pop culture doesn’t exist. Being in a digital literary clique is a tiresome fate for writers in the 2020s. No one is watching them. No one is thinking about them but each other. It almost reminds me of how teenage boys play Call of Duty on PlayStation Online and they have their army and they are strangers but it’s not being televised, it’s just them watching…

RG: Is there anything contemporary you consider to be chopped?

AK: The 1975. Matty Healy has been so supportive and kind to me. I love The Shards as well. I don’t know if I’m a fan of contemporary culture? I need to be exposed to more. I’m drawing a blank.

RG: In the 1990s, grunge miserabilism became a currency, and teenage alienation and outrage just one more angle with which to exploit an advertising demographic, creating its own capitalist vortex. From misery porn to victim culture, do you see a direct line from the turn of the millennium to now? How is this issue addressed in the novel?

AK: I think this is the biggest mind-fuck of Gen Xrs/Millennial-X cuspers. You have one person at the table saying “Fiona Apple is a bleeding-heart genius who is so pure and a once-in-a-lifetime talent” and then you have another person, chain-smoking, talking about “Fiona is a corporate clone, designed to sell ‘female angst,’ so Lilith Fair promoters can make money.” I think what you are saying is on the nose: grunge miserabilism, teen alienation—everything became a currency to exploit.

I think the issue is addressed in the novel in the way the boys are so contradictory of themselves. They are old enough and smart enough to see how everything they love is a gimmick, and yet they are absolutely obsessed and entranced by those gimmicks, resulting in an entire total loss of self. It’s this mind-bender experience that really troubles their daily life, because they crave authenticity and something real, and yet they know everything in this time period has a spin, an angle.

RG: “What’s up, motherfuckers? This is the last night of the millennium. Nobody in this room is ever going to feel this way again. I know you all may think that you came here for an end-of-the-world party, but nah, I’m going to tell you some shit. Listen up: it’s not the end of our world, it’s the end of their world. We are the new generation that is going to change the fucking world. Uranus is in Aquarius and they cannot stop us. We are the online kids. We don’t need Newsweek to tell us shit about ourselves. For the first time in world history, we have control over our own lives. We get to curate our own reality. We get to choose what we simulate, what we see. We connect on message boards, in chat rooms. We can burn our own CDs, make our own fuckin music, our own brands, be our own brands, and share our visions with the whole world. I get DJ tips from dudes in London. The possibilities are endless now that we have the passwords to culture. We are hacking the planet. We are the fucking illuminati.”

A standout moment in the novel is the Y2K party, a debauched David LaChapelle and Jonas Åkerlund-infused bacchanal. The surreal sensory overload of fashion, chemical, and sexual combinations must’ve been fun to write. Is the planet hacked?

AK: FYI, I am going to be texting Jonas tonight and telling him you described the Y2K party scene as “an Åkerlund-infused bacchanal.” It was fun to write, and stressful, because I know Y2K apocalypse aesthetics are so important to youth today, and I wanted to really put the pressure on myself to create something fun for the reader. This planet is hacked, and the planet back then was hacked—all it took was dial-up internet.

RG: “No one gets it, dude. People don’t know what it’s like to wake up, look at your reflection, and feel like your life is happening to someone else. It’s not apathy. It’s not detachment. It’s something way more mysterious.”

For the kids you describe, self-awareness isn’t enough to get them out of trouble, at least in the short term. A way of thinking has become so deeply embedded that to combat it necessitates the deconstruction and rejection of part of who they are. For me, this is the central tragedy, that those most in need of a centered sense of self are struggling to find it in a world that makes its acquisition enormously unlikely. They are set up to fail. Every one of us is one or two bad decisions and life experiences away from disaster. When you reflect on the book now, how do you feel about it?

AK: I think a big point you are making is that you can tell these teenagers are really just children and that the reality of life and all of its violence is not something they can conquer. It’s something so powerful that it will destroy them and it does absolutely that. No existential thought can prevent or keep these characters safe.

I think the way I feel about New Millennium Boyz changes every day. I do think I took some bold risks. I can sort of see the stubborn teenager inside of me I tried to make happy, I tried to complete his vision, and I think I did. I do like the idea of people thinking of the novel as a 300+ screenplay because I guess that was the goal: “minimal narrative voice, lots of dialogue, imagery to set-up the imagination of the reader.”

I think the way I feel about New Millennium Boyz changes every day. I do think I took some bold risks. I can sort of see the stubborn teenager inside of me I tried to make happy, I tried to complete his vision, and I think I did. I do like the idea of people thinking of the novel as a 300+ screenplay because I guess that was the goal: “minimal narrative voice, lots of dialogue, imagery to set-up the imagination of the reader.”

RG: As music is so central to the novel, could you recommend some tracks for those who want to prepare themselves for New Millennium Boyz?

AK: “Affirmation” – Savage Garden

“Barely Breathing” – Duncan Sheik

“Say What You Want” – Texas

“Sick Of Myself” – Matthew Sweet

“Celebrity Skin” – Hole

“The Dope Show” – Marilyn Manson

“Special” – Garbage

“Heavy” – Collective Soul

“Velvet Rope” – Janet Jackson