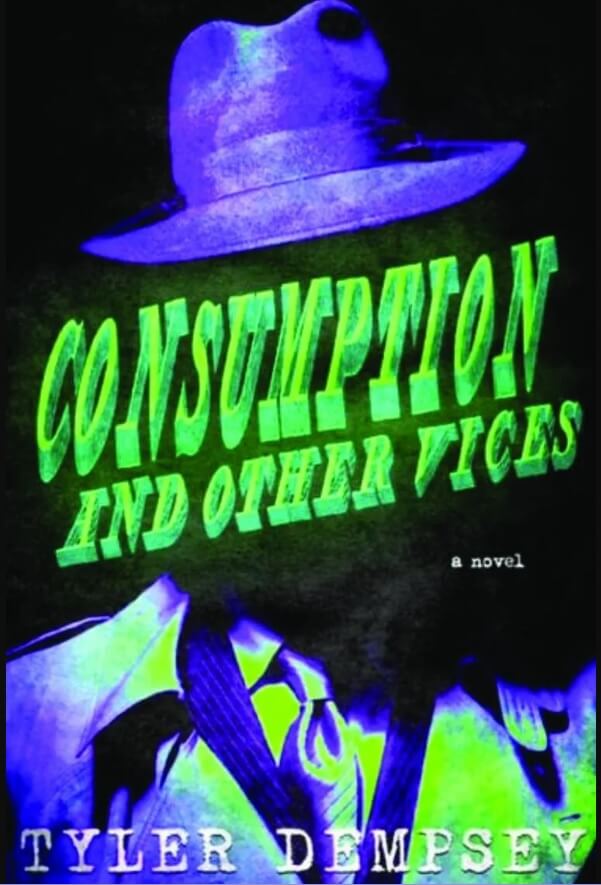

Every small town has one. An event that turns a provincial backwater into a place where that thing happened. For Consumption & Other Vices (Death of Print, 2023) Tyler Dempsey strips a town bare, distilling the monstrousness that lurks beneath its surface. Bad choices stalk the trees, and damaged appetites are satisfied in lonesome buildings on the outskirts. Dempsey’s novel captures ruined lives with intense brevity, and quests to recover sense from the ultimately senseless.

Every small town has one. An event that turns a provincial backwater into a place where that thing happened. For Consumption & Other Vices (Death of Print, 2023) Tyler Dempsey strips a town bare, distilling the monstrousness that lurks beneath its surface. Bad choices stalk the trees, and damaged appetites are satisfied in lonesome buildings on the outskirts. Dempsey’s novel captures ruined lives with intense brevity, and quests to recover sense from the ultimately senseless.

Rebecca Gransden: “Small towns. They’re such nightmares. Postcard-perfect, but Dahmer’s flipping omelets.” Bloomington is your small town of choice, a place as nondescript as any other, its residents hanging on to a fading church or old time superstition. Do you have experience with the small town state of mind? Is the vision of Bloomington you present taken from the real place, or is your town a complete invention?

Tyler Dempsey: In the 90’s and early 2000’s, I went to school with 45 kids in rural Oklahoma. Think poor. Bible Belt. The population of the “town” my family’s from (as of 2000) was 332. There’s a Post Office. No gas station. No red light/restaurants. Nothing. Mom was a single parent raising two kids on $4.25 an hour. Not too unlike what the other households looked like around me. As an adult, I lived 13 years in rural Alaska where seasonal summer populations topped 1000, but the year-round number was about 100. Bloomington is fictional. But, to say it’s a complete invention would be lying. Its streets are from my imagination, but the people and energy are real.

RG: Consumption & Other Vices makes use of a strikingly spare prose style. Was this stylistic choice one with definite intent or more instinctual?

TD: The story came to me through dreams. Very little’s going on in dreams. Detail-wise. You’re going to a place in a car. Whatever. But in this space, void of details, you’re more afraid than ever. Why? It’s like the brain is working in a 4th dimension.

Once, I was charged multiple times by a bear. Time slowed, and I never actually felt scared till afterward. Once everything was okay. I can still remember its hair whooshing. The smell of the trees. I was so hyper- and narrowly-focused. There was nowhere for my mind to go. Dreams are the opposite. Time is moving fast. Details blurry. There’s little in the moment to cling to. Which is why we rarely remember them. There’s a larger plane outside the moment for our mind to move around. For focus to stretch. You still can’t see or change the future, but you have prescience. And what you’re moving toward is what’s scary.

I wanted to try that with text. Thought, could I ramp up the speed with which things were happening and how the reader was experiencing them, and leave a noticeable hole where the details should go, where the hole became a presence in their room, where they could start to feel what was coming? Maximalism pushes readers from the equation. Like meeting someone at a bar and they do 99% of the talking. Which—if the person’s smart/interesting enough, sure. But I love when not only is the writing sparse, it’s obvious the author’s done the work. Anticipated what you’ll be thinking. Given just enough to make you think it. A reader’s imagination is invited as the 3rd person in the room. To share in creation.

I read Edmond Jabés the first time 11 years ago. His books are plugged as poetry. But I remember thinking, these are novels. Peter Markus can do a similar thing when he really gets humming. Both were inspirations for this book.

I read Edmond Jabés the first time 11 years ago. His books are plugged as poetry. But I remember thinking, these are novels. Peter Markus can do a similar thing when he really gets humming. Both were inspirations for this book.

I guess I was most interested in challenging myself. Seeing what was possible. How much could I bring a reader in? Small towns and noir seemed great vehicles to pull that off, cause our imaginations are laden with tropes and pre-existing judgements. I thought, if I can get them there. Show we’re sitting at the same table. But, spin it enough they remain off-balance, wouldn’t that be fun?

RG: Noir as a genre brings its own baggage. I found your approach imbued with freshness and immediacy. What attracted you to tackle it?

TD: I wanted to try. I love the genre. Double Indemnity was huge for me. And books by Georges Simenon. It’s like I equate the genre with a timestamp. Get that comfort and sadness and nostalgia I feel when Sam Elliott’s narrating The Big Lebowski or that scene in The Sandlot where the characters start to disappear in front of you and it’s saying where life ultimately disappeared them to. Or, watching Stand by Me or The Hudsucker Proxy, or on and on and on.

It resonated when I heard Georges Perec’s goal was to never write the same book twice. I just finished an autofiction novel. Someday, I’d like to try a western. It doesn’t do much toward building an audience. Switching expectations like that. But I don’t have much of an audience so I should really just be doing this for fun. More writers should just be doing this for fun, I think.

I’m happy I tried noir. Had a helluva time in that world. ‘Preciate you saying it was fresh and immediate. That means a lot.

RG: Jane and Clara are your victims, their deaths the central mystery of the novella. What elements did you consider when constructing them as characters, as they are known only through the eyes of others?

TD: There’s danger and falseness in viewing others. I’m a true crime junkie. Shittier, the better. In those shows you often get the victim’s story through their parents. Boyfriend. Siblings. Friends. Never them. The narrative’s circling but never touching them. And always, always, whoever’s got the mic makes it a little about them. Because, not only are we self-absorbed monsters, but everyone’s someone else depending on who’s in the room. I find, more times than not, the victim and their intentions get lost the more we learn about them through others.

Every character in my book is guilty of making Jane and Clara the biggest story of their own life. To me, that’s one form of “consumption.” When someone’s voice is drowned by the desires of others. The book eventually tells you what happened, and I hope in a pleasing/rewarding way. But the “mystery” that continues, what was most intriguing to me, was, who the fuck are these people? As you learn more, the lens gets blurrier. Just as the story’s dots are connected, characters slip between your fingers.

RG: Some of the most arresting sections of the novel come from the point of view of the perpetrator of the crimes. The language is fragmentary, suggesting fractured thought processes, but also a worrying focus on a narrow set of goals. At times severe mental health issues are hinted at, perhaps exacerbated by drug use and an altered state, as thoughts cycle, and a disordered mind perceives outside forces at work and communication forthcoming from inanimate objects. How did you go about representing the mind of your killer?

TD: I sat on the detectives’ angle of the book for a year. It was all finished. I knew I wanted to grow the story/world but didn’t know how.

This is gonna sound crazy, but my grandmother saved my uncle from suicide twice. Once she dropped the dish she was washing and ran all the way to his house. Caught him just in time. Said, she just knew. I’ve suffered auditory hallucinations twice. Get this: I knew who the voices were. And, less than a week later, in both cases, the person was dead. I don’t know what that means. But I think what I believe, is our minds are antennas. And, just like if you have two radios, one in each hand, one might transmit a message the other only broadcasts static. Or, doesn’t pick up at all. I think my grandma picked up my uncle’s signal. Even if others couldn’t. And I picked up my now-dead friends.

So, I’m sitting on my half-finished noir. I wake up one morning (when we’re really sleepy, when we just wake up or are about to fall asleep, our antennas are most receptive) and all at once I pick up this station. I’m hesitant to call it a person on the other end. An energy or demon, I don’t know. But I see how it could take over a person. Its rhythm of thought, way of speaking, is cyclical, almost hypnotic. A spell. It’s evil. Primordial. At most semi-human. Before we evolved to have morals or empathy. Very strange to be talking about, but it’s what happened. I didn’t have to think about it, I knew it was the other side of my book. Like when a puzzle piece pops down, was the feeling. I hopped up and started writing. For the next two weeks I could pick up that station any time I wanted. I don’t think that half of the book was written by human consciousness.

RG: You make use of repetition in a compelling way, especially when it comes to the inner monologue of (who we assume to be) the culprit, as they recount events. Place becomes infused with meaning, as recurring motifs reassemble themselves, suggesting a churning state of mind. There is a mantra-like, ritualistic quality to parts of the novel. How do you view your use of repetition?

TD: I was truly broadcasting a signal. More translation than writing. It’s obvious this thing, whatever it is, has limited language and scope. Its vocabulary is only as developed as a toddler’s. It was very interesting to write. Quickly realized, traversing this mind was much like traversing a labyrinth. Any new thoughts or words cycled back into the maze. But as it did, again and again, something happened. Reading or hearing it, it starts to work on you. This sing-song’edness to it. It builds. Becomes grosser/weirder the more you hear these fixations repeated. What it taught me was language can possess someone.

TD: I was truly broadcasting a signal. More translation than writing. It’s obvious this thing, whatever it is, has limited language and scope. Its vocabulary is only as developed as a toddler’s. It was very interesting to write. Quickly realized, traversing this mind was much like traversing a labyrinth. Any new thoughts or words cycled back into the maze. But as it did, again and again, something happened. Reading or hearing it, it starts to work on you. This sing-song’edness to it. It builds. Becomes grosser/weirder the more you hear these fixations repeated. What it taught me was language can possess someone.

We’ve all known or been The Extremely Depressed Person. Certain words become mantras. Till finally, one day, the spell breaks. The culprit in the book is what I believe a person who was hollowed into a puppet by this energy or demon I was picking up on would become. The repetition gives the book a horror-adjacent feel. Like Jason Voorhees or Michael Myers walking, not running, toward their victim. There are times the text seems to progress painfully slow. But the dread builds and builds.

RG: At times your use of repetition put me in mind of the repeated rhythms of a small town, where each day unfolds in a habitual way. Driving the same roads creates a familiarity that is comforting to some, suffocating to others. These sorts of towns have areas that become like labyrinths, as every street can end up looking the same, and then each town adopts the character of another, with the same stores, and style of architecture. In this way, the residents too become archetypes, slightly adapted versions on a theme. This adds a sense of predestination to the novel, that events, while monumental to the individual characters involved, become reflections of a larger and more menacing force at play. Do you have any thoughts on predestination in relation to the novel?

TD: Yes. Can I say yes? Hah. No, that’s it. There’s something repetitive, similar to this dark energy I was channeling that resembles energies of small towns. Of hopeless, dead-end reality. Prison, at its base element, is repetition. You hear all the time people “escaped” their place of upbringing. That’s what makes small towns creepy. Chances to break the cycle are so slim. Luck is the only thing that helps us shake off that energy. Even a judge in a courtroom is only up there cause they didn’t get pulled over the handful of times they drank and drove. Just as easy they could have ended up bagging groceries at Dollar Saver.

There’s a lot of resentment that entrapment breeds. Where people will sabotage you to keep you existing at their level. It creates a vacuum of hands reaching out of the earth to pull you in. Whether people in these places are aware, it’s happening to all of them to various degrees.

RG: A theme in the novella is one of breaking the monotony and routine of small town life. Jane and Clara do this in order to inject some excitement into their existence, putting themselves in risky situations as a result. It seems as if all small towns create their dark underbelly out of a twisted necessity—that it is an uncomfortable truth of human nature that boredom will be challenged at any cost. These violent events allow seemingly innocuous locations to take on heightened meaning, creates an intensity lacking in the day to day of such a place. Ordinary homes become notorious, and allow inhabitants of the town to look upon their environment with fresh eyes. Do you have any insight into the language of myth-building that evolves in small towns? Any real life examples you’d like to share?

TD: With so little to do, with repetition tightening its grip on your neck, you start hunting for alternatives. If you can’t find something to do, maybe you can make something find you? It’s why these places house strange, interesting people. Characters. Because things happen to characters.

You’re definitely right that places get imbued with meaning. Boredom is a rumor mill’s best friend.

There’s a park in my hometown. Fairly large, wooded, hilly. I remember people talked about how a Satanic cult used it for rituals. One time I found globs of different-colored wax candles in a circular pattern way off from the trail. Everyone knew the rumors. Likely some kids did it in hopes someone would stumble on it and somehow it’d get back people were talking about it.

I had an uncle who made plaster casts of Sasquatch feet. Put them on the end of broom sticks so he could stay high on a bank above a creek making footprints down in the sand. It made the newspaper, much to his delight. My friends and I used to go to cemeteries or abandoned homes that were supposedly haunted. Creepy stories/myths are rampant in rural places. It starts as a little fun to break monotony. But there’s a chance some copycat will come along and turn someone’s myth into reality.

I had an uncle who made plaster casts of Sasquatch feet. Put them on the end of broom sticks so he could stay high on a bank above a creek making footprints down in the sand. It made the newspaper, much to his delight. My friends and I used to go to cemeteries or abandoned homes that were supposedly haunted. Creepy stories/myths are rampant in rural places. It starts as a little fun to break monotony. But there’s a chance some copycat will come along and turn someone’s myth into reality.

RG: When reading, I had the feeling I too had been cast as a detective, which in a wider sense any consumer of mystery stories is. The narrative takes on the form of a detective’s notebook, in that the succinct style selects which information is significant, curating reality from a specific point of view. In this way any reader is left to home in on relevant info, sort through what has been noted on the page, and also consider what details might have been omitted. This is unnerving, as it underlines the ultimate impossibility of the attempt to have concrete answers when it comes to the messiness of human interaction. Did you consider reader role when writing?

TD: I like the game Clue. Whodunnits. That distrust they breed. Where, with time running out, the butterflies in your stomach lift up. I created a swirling narrative where you get a lot of info but it all comes from different sources.

A detective has to be weary. Assume they’re being lied to. I wanted the reader to adopt that approach. Wanted to give enough to support theories, but not facts. And then, at a point, flip a switch. Where it becomes clear the characters that were supposed to be providing you reality obviously don’t have two feet planted there. And you’re left not knowing who to trust.

Readers who need to be given everything to be fulfilled by a book won’t like it. Probably they’ll feel duped. But people who like mystery for the mystery of it, books for language and poetics they bring, they’re who this’s meant for.

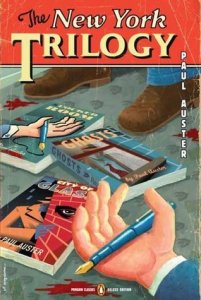

RG: Your characters Detective Andrews and his partner Shupbert are those tasked with investigating the killings. They have removed themselves from their division’s main working environment, seeking a stillness away from their colleagues. In this way they share the outsider status common to those they have under suspicion. At times I was reminded of the metaphysical detective/mystery stories of Paul Auster’s The New York Trilogy, where the narrative draws attention back onto itself. Andrews and Shupbert seem as intrinsic to events as all other players, their parts as essential and complicit as any other. How did you go about creating your version of the noir detective?

TD: It’s crazy how close you read this. I’ve never checked out The New York Trilogy, but maybe I should?

TD: It’s crazy how close you read this. I’ve never checked out The New York Trilogy, but maybe I should?

The book offers parallel stories, which are actually a circular mirror. Seemingly opposite characters/places that are complicit. Andrews is mysterious and spiritual, Shupbert grounded and not. Jane is dangerous, eager to take risks, Clara’s quiet but along for the ride. A killer, whose voice is present throughout the book, is ratted out by a minor character who can’t speak. City detectives drawn to an idyllic countryside, those in the country eager to escape to the city. Not to mention the last line of the book is also the opening one. Division between crime and justice is paper-thin.

Mostly, we’re only ever investigating ourselves. Our own obsessions. I’ve always been fascinated by fascination. The police are almost always obsessed with crime. Firefighters are the first blamed for starting fires. It’s often the virus itself used to create the vaccine. That sort of thing amazes me. I wanted a noir detective that riffed on that idea.

RG: Could you talk about your use of ambiguity, as I feel this is central to the novella’s character?

TD: Life’s ambiguous. Mystery’s no longer mysterious once Scooby and the gang are accused of being meddling kids. But ambiguity magnetizes curiosity. The things we don’t understand, can never understand, are what we write about.

I tried creating a curiosity. That would linger. The mind would come back to. Would invite rereading. And again, playing with a mirror of opposites. Danilo Kiš has a line in Homo Poeticus—something like, “The author’s task is not chasing ambiguous words, your goal is clarity.” One goal, with the sparseness of the detective text, was to be as clear as possible. No flowery adornment. Like you said, jottings in a notebook. The facts. No distractions.

With the perp, you get these words, Mama, Papa, Truck, Road. Now, normally, those are pretty concrete, but through the mouth of this weirdo, evoke dissociation. This isn’t to fuck with you, I’m trying to get your curiosity to sit up. I’m not into digressions, but I do love a complex, confusing triangle of ideas.

RG: The novella focuses on those lives that are lost, people who manage to stay on the fringes of small town life. Do you have any insights into why these towns foster such figures and why we keep writing about them?

TD: They’re beautiful. Everyone believes there’s something more out there. And if we were just braver, had more time/money/whatever, we’d Don Quixote it up. Live the life we were designed for. Chase down our desires. But there are too many narratives/expectations/obligations pinning us to 9-to-5 existence. Least, that’s what we tell ourselves. So, these fringe people are kinda badass.  To steal from my writer friend, Brian Allen Carr, they’re the Diogenes. Poor, but happy. Cynically reminding us how fake normie life is.

To steal from my writer friend, Brian Allen Carr, they’re the Diogenes. Poor, but happy. Cynically reminding us how fake normie life is.

As to why small towns foster them? I don’t know. It’s gotta be a numbers thing. Anyone in a small town is related to at least one person you know and care about. Or related to someone who’s related to them. So, you kind of care about them too. It’s James’s cousin Eddie; they’re a little off, but you get used to them. Once you get into a city though, they become strangers. Easy to step over them and the newspaper they sleep on, put in your earbuds and ignore them. They’re simply strange, because they’re strangers.

RG: Feeling like someone else, a type of dissociative, numbed state impacts the characters, and dark dreamlike visions suggest some type of possession. How did you approach the incorporation of supernatural and occult themes in the book?

TD: They’re based on feelings and experiences I’ve had. Throughout life, there have been moments of dissociation from my own physical body. Suddenly some part of me or even my mind feels alien. Then snaps back.

I had a period in college leading up to my best friend’s brother’s suicide where I started seeing and hearing things. My best friend did too. Not hallucinations. I mean real, terrifying shit. That tall, shadowy figure with arms extending past its knees is something I’m familiar with. If anyone reading has seen it, you’re not crazy. There are times when the supernatural reaches in our world, fucks around, and leaves. Too many people have experiences with it for it to not be true.

RG: Who, or what, are Bloomington’s ghosts?

TD: Aside from the actual ones described, the same as any small town’s. The boredom and loneliness and predetermination all chipping the walls of your sanity over time. Paints a pretty good image of what it feels like and I think the mind has this way of shooting us through the future. Maybe that’s why montage scenes work? But yea, to sit there, sort of shoot your way through an imagined future of boredom and loneliness. Takes on a gravity that nearly rips you off your seat. It’s haunting.

RG: “Consumption” in the simplest sense, means the using up of available resources, which certainly can be directly applied to Jane and Clara and how they are used by their killer. Why did you select that term as the title for Consumption & Other Vices, and what are the other “Other Vices” as you see them?

TD: Our culture’s fiendish for gobbling things up. There are great quotes that encompass it, but I love Ed Abbey’s, “Growth for the sake of growth is the ideology of the cancer cell.” Possess and consume should be lasered into marble above the door of every business. Fulfillment and happiness are the opponents of consumerism. So our every moment’s been tailored to make us sad and unfulfilled. I think about tuberculosis, how it was called consumption at first, cause the weight loss associated made it appear the person was being consumed by the disease. There are plenty of other vices, but consumption reigns. It’s also just a cool ass title, isn’t it?

RG: I’m aware that this interview itself is another interrogation, perhaps an attempt to solidify the ineffable. For many writers, their work is something they only begin to comprehend on a rational level in hindsight, if they choose to look back at all. As you reflect on the novel, has anything come to light that has surprised you? Any revelations after the fact? How do you feel about talking about your work?

TD: That’s true. The surprises came during writing. At this point, it’s been years since I finished. I’ve already written another book.

TD: That’s true. The surprises came during writing. At this point, it’s been years since I finished. I’ve already written another book.

One thing that’s no shock, but always kinda weird, is how you move away from the person you were while working on a book. I have a hard time believing I wrote it. Consumption is a bizarre specimen I could never write again. One day I might uncover the manuscript in an old box. Pick it up, start reading, and wonder who wrote it? It’s difficult to talk about art. To pin it down. Makes me appreciate even more the people willing to come on my podcast and try their best to do it.

Read Tyler Dempsey’s previous contributions to X-R-A-Y.