She had only applied to work in the Halloween store because she thought it would be temporary. But this store was open year-round—the building owned, not leased, by a man named Ed, who was thin and wiry, nostalgic and ambiguous as a figure in a Grant Wood painting. The devotion he extended to the rows of ludicrous masks and cackling witch animatronics seemed more suited to the motions of a farmer, tending to something whose harvest would keep people alive, rather than fleetingly amused.

Ed preferred silent, solitary work: keeping inventory, tracking shipments in the back room he seemed to live in. He wanted someone to take over the register, be more “front-facing.” “Are you a people person?” he asked her when she first came in. She lied and said yes.

In the Halloween store, time was always running out, yet somehow not passing at all. Ed’s business philosophy consisted of keeping a permanent GOING OUT OF BUSINESS sign out in the front window to create what he called “a false sense of urgency” in the customer. The music that played during her shift was always the same recording Ed had made of a Top 200 countdown on Labor Day 1993, commercials and all, every day climbing the same apex towards “Heart-Shaped Box.” Then it would start its loop all over again, trapping her inside. She would think of all the other times she had heard these songs over the course of her life—these same songs again and again and now, a million times more. They were engineered for liminal spaces: checkout lines and waiting rooms and traffic jams, to give people the illusion of movement and rhythm when their lives were going nowhere. Usually this time of year, Christmas music took over, the ultimate opiate of the masses, to distract everyone from the cold fact that another year was slamming shut forever. But not in the Halloween store. The music didn’t change. It never would. That would mean something was coming; that would mean something was ending.

To stay afloat, the store also sold other holiday items, stocked as if they were perennial: pastel Easter baskets of unraveling wicker, Thanksgiving wreaths of fake papery leaves, snowmen whose bodies were made of Styrofoam and crumbling glitter. It was the snowmen’s season now: winter, at least by some definitions. But this was Florida, and the seasons never really changed, not in any meaningful or significant way. That was her favorite thing about coming here: the pure indulgence in wasting perfect days, because they were in seemingly infinite supply. It didn’t matter what she did or didn’t do with each one, because another would reappear the next morning, new and clean and glaringly bright. She couldn’t possibly be held accountable to change if nothing else around her did.

The store was listed on various obscure websites and in off-brand guidebooks as an “oddities destination,” although the people that stopped in were always on their way to somewhere else. Usually, they would stalk the aisles for a minute or two before walking back out empty-handed, muttering there wasn’t much to see, just the same old shit you could get anywhere in October. “Speak for yourself,” she would think as she watched them leave, staring out the display windows into the vanishing point of the horizon. The store possessed the most beautiful natural light she had ever seen in an interior space—that was its most extraordinary quality, what should have been advertised in the guidebooks. Every afternoon, the golden glow that seeped in and wrapped around her nearly brought her to tears. Its beauty had something to do with the time passing, a phenomenon that persisted outside the safe confines of the store. The light was a reminder that life was short, something which was easy to forget whenever she was inside. Even Ed’s sign out front was only a false alarm—time running out rendered merely a marketing tactic and as such, a lie.

She came home at night smelling like the plastic that everything in the store was made from, the way she used to come home smelling like coffee when she worked at Starbucks, her first job, her first failed attempt to make a life for herself. But unlike the way coffee’s nutty sweetness had begun to smell foul, the pungent scent of the plastic began to smell not quite sweet, but the next best thing: unnoticeable. Like how when she was a child she realized that all of her friend’s houses had their own special scent, but she could never smell her own. The place she came from always smelled like nothing, like it wasn’t a place at all.

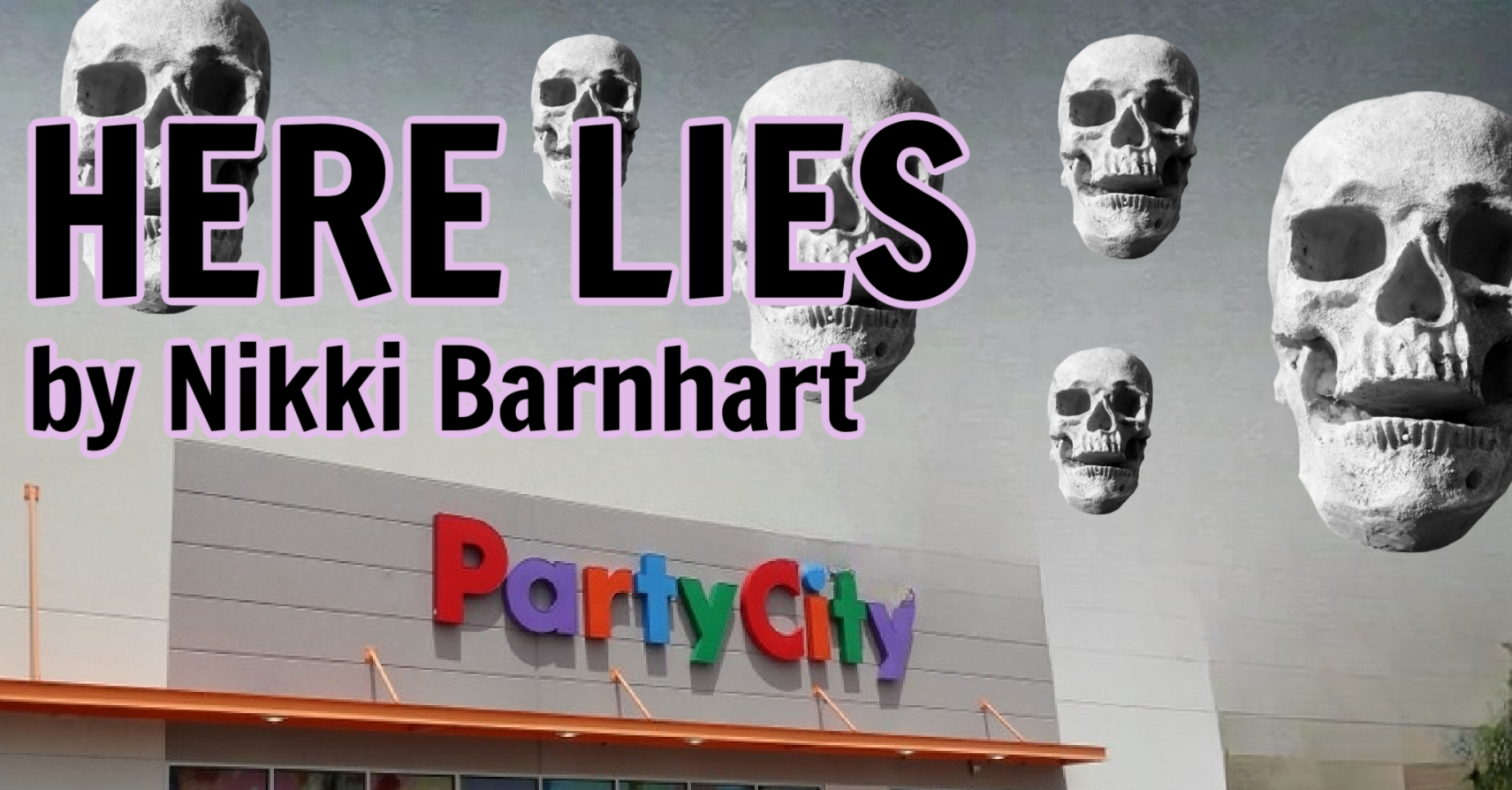

From her view at the counter, she could see the rack of personalized tombstone decals, some of the store’s best sellers. People thought it was hilarious to pretend to be dead. HERE LIES ADAM. HERE LIES ANNIE, they went, and so on. She could see her own name hanging there, a straight shot at eye level. When she interviewed for the job, Ed had asked her what scared her the most. She considered the question, really thought about it. But then too much time had passed so she just blurted out, “Nothing.” The word lingered in the stale air of the store. She could sense it hanging over her, like a spirit. She felt it, she believed in it, but that didn’t make it real.