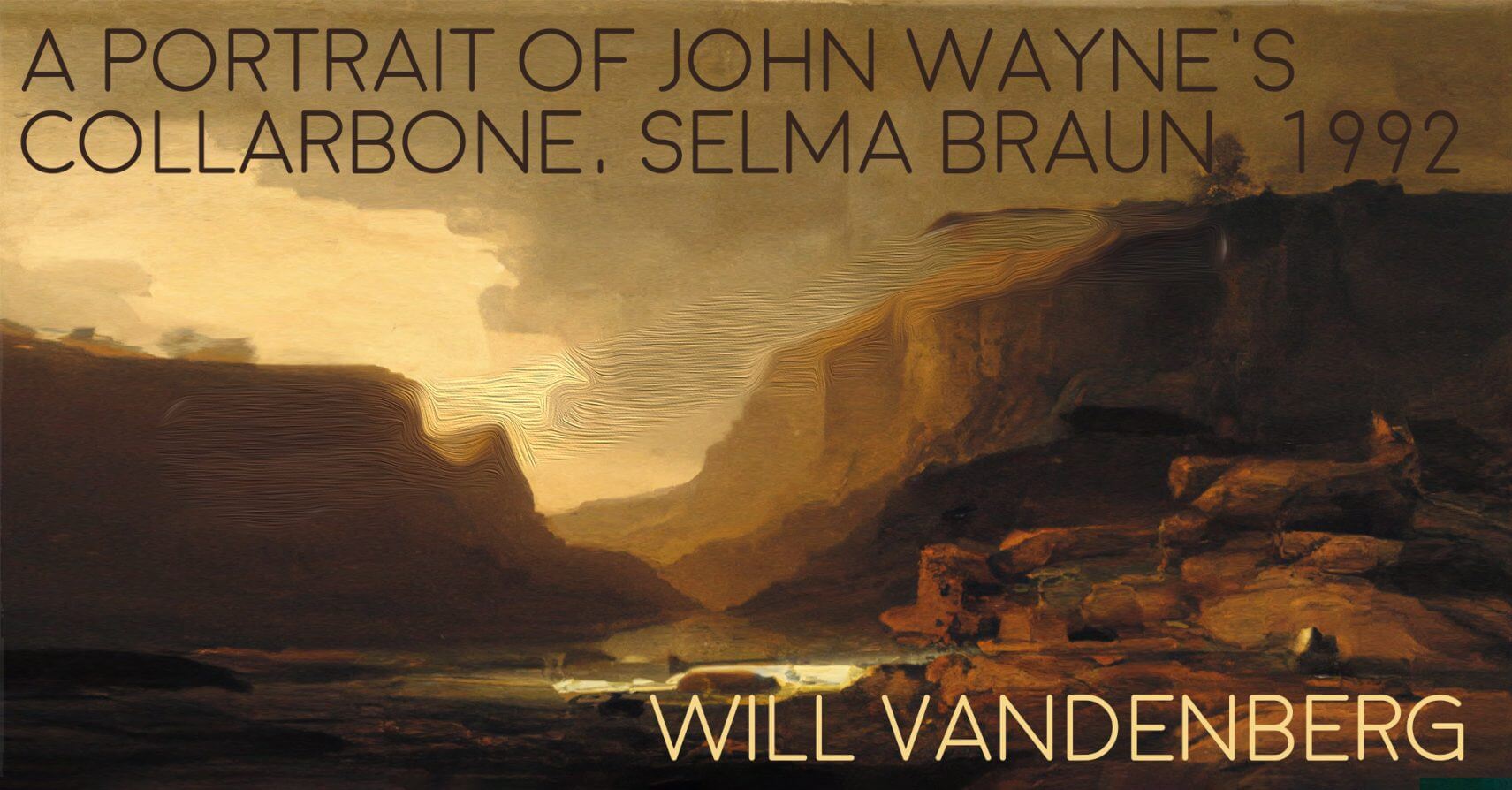

The Painting

Landscape, 9 feet by 10 feet. It’s part of the artist’s monumental airborne objects series. Daytime, western scene. A canyon splits the red-brown foreground and winds down to the bottom edge. Trees—varying between black and navy green—stick up above the canyon wall. At one bend, the wall gives way revealing deer drinking water from a narrow stream on the canyon floor. It’s inaccurate—deer wouldn’t drink in daytime, instead waiting until safety of nightfall to journey down from the mesa hovering in the distance.

In the sky above, a gigantic collarbone floats. It covers nearly a third of the painting. Its shadow drapes across the foreground, sheltering the deer from the worst of the heat. A poorly repaired crack identifies it as John Wayne’s. He sustained an injury which kept him from a football scholarship. The two halves of bone don’t line up, the left side higher. The connection bulges. The injury occurred in a bodysurfing accident in southern California in which a tourist violently collided with the Duke’s neck.

Terms and Conditions

The deed stipulates the painting’s primary residence as the Gagosian Gallery on W 24th for a year after the sale. It can only be sold following the death of the artist. Her ex-husband will (having agreed to a cut of the sale price) painstakingly paint the floating collarbone out of the scene, leaving only the landscape. The act will be done in public view. The ex-husband, while not a formally trained artist, received exhaustive instruction from his wife during their decades together. The sale will be made only if these conditions are met. Otherwise, the painting will be transported to an undisclosed, remote location in the American Southwest, defaced in a manner as to make it unrecognizable, and left to succumb to the elements. The purchaser will receive no refund.

Horse Opera

It’s 5:34 am and John Wayne is singing to his horse. The shoot is behind schedule; they’ve gone all night. Wayne’s singing voice will be dubbed over. On set, he tunelessly half-sings so he remembers to keep moving his lips. His first starring role a failure, he is relegated to a sub-genre of B westerns called “horse operas” on account of common musical scenes in which the lead cowboy sings to his horse. In this one, he isn’t even the lead, instead sharing co-lead status with a washed-up silent film star. He gets the singing scene only because the other lead refuses.

This is Wayne’s sixth western this year. It’s July. The director shot a cheap submarine picture last year that Wayne auditioned unsuccessfully for. Solid script, but the sets were cheap, the whole thing shot in 15 days. In the end the lead commander goes down with the ship, torn apart at unsustainable depths. After the audition, he complimented Wayne’s sense of presence but said, “No one rides horses on submarines, Marion.”

As the horse’s lips chew the ill-fitting bit, the director remembers the prior weekend in which he invited Wayne to his house for dinner. He has three kids. He doesn’t care much for Wayne, but his children like it when he brings movie stars around, even if they prefer Gene Autry. Before dinner, they and several neighborhood kids climbed all over him, seeing how many it took before he could no longer walk (six), eventually hauling him to the ground where they tickled him until he was red in the face. Before they ate, the director caught Wayne massaging his collarbone, a wince cracking his features.

The director’s father lives with them. The director moved from Germany before the start of the war. He doesn’t talk about it. He was a director back there as well. He couldn’t find work for a year before they moved. They sold everything they had. A friend got him work on low-budget instructional films. First as an A.D., then moving his way up. There’s something wrong with his father. He doesn’t talk about it. The old man hasn’t spoken for months even though physically he’s fine. At dinner, he peers up at Wayne for the first twenty minutes as the children’s chatter clogs the air. A deep crease works its way between his wild eyebrows. He tries to remember. “Di Oppenheim,” he sputters, voice gravelling to life. In a language Wayne doesn’t understand, the director’s father continues. “It hung above our mantle. Junge Herr Eine Kerze Haltend, it was called. A boy held a candle, his cheeks pink, the holder dull gold with a flared base and a hook for the thumb. But the hook—it is sharp, barbed like an arrow. Surely he would catch his thumb on it. It hung above our mantle.” The old man turns to his son. “Where is it? Did this man take it? Show me the painting, now,” he demands.

Wayne stares uncomprehendingly, looking to the director for a translation. The director lies. “My father says he likes your work,” he tells Wayne, and he does his best to calm the old man. He does not tell him the truth; he does not tell him the Oppenheim was sold. He tells him he will show him the painting after dinner. He tells him Wayne is their milkman. The father likes this gesture, the invitation of a common man to dinner. He quiets. The line between his eyes smoothes. He nods. Before returning to his food, he says to Wayne, “The boy’s eyes were green,” but not exactly that. He uses a word that means, “a green so bright it is past comprehension,” and then returns to the speechless hollow of his mind.

On the soundstage, Wayne curls his hand toward his collarbone, a gesture of protection. The director likes it. It reads as a sign of affection for the horse, a clutching of the heart. The horse’s lips reach toward Wayne. He probes the collarbone with the tips of his fingers. He finds the hairline crack the climbing children made. His voice gives out, but his lips move for another line or two before stopping. The lights on the soundstage buzz. “Again,” the director says, and Wayne collapses to the floor.