I took my date to see the dead calf I love. I didn’t tell her about the calf upfront because I wanted it to be a surprise.

I met my date through work. She edited the classified ads in the paper I distributed each morning. She didn’t know me or know anything about the paper-distribution process. Her colleagues didn’t either. Their stories had a deadline of midnight and that was that—they were unbothered by everything that came after.

But my editor wanted to see the process through and asked to ride with me along my paper route. I showed her how to fold the papers. I showed her how to twist her wrist to land the paper close to front porches. I told her I liked imagining families gathering by the paper in the morning. I liked imagining myself watching from outside. She closed her eyes and pretended the families were perusing her carefully edited ads.

When the route was over, I parked in a left-turn lane so that the car shivered along with passing morning traffic and there we watched the sun rise. I asked her then to accompany me on a river float trip. I was not surprised when she said yes.

Together we enjoyed lukewarm beer in neon-blue tire tubes on the river. She put a gluttony of sunscreen on her nose like lifeguards do in movies. Our tubes spun off each other’s and we took turns dragging one another out of mud banks when our bodies got sucked in. I tried to pretend I was new to tubing. My editor was not very good and I didn’t want her to feel like she belonged less on the river than I did.

But really I spent most of my free afternoons in a big blue tire in the water and in the mud. I bought the tire after my few first trips down the Midwestern deltas because I thought it would make me more interesting to the strangers in my float group. I wanted people to see my custom tube and become intimidated by my devotion. I wanted them to see me and think that maybe they were missing something.

That girl—I thought they thought—is more fulfilled than we are.

I was on my third trip when I first saw the calf. The land itself was very sparse; anything that grew above ground was usually living and on legs. I had been drinking on the trip and thought the calf was a tree. I shared my excitement with the burned neck of a stranger bobbing his tube before me.

“That’s not a tree.” He did not turn to face me. He reached out to his float partner and put his hands over her eyes. “You might want to look away.”

He did not say this to me. I still heard. I didn’t take his advice.

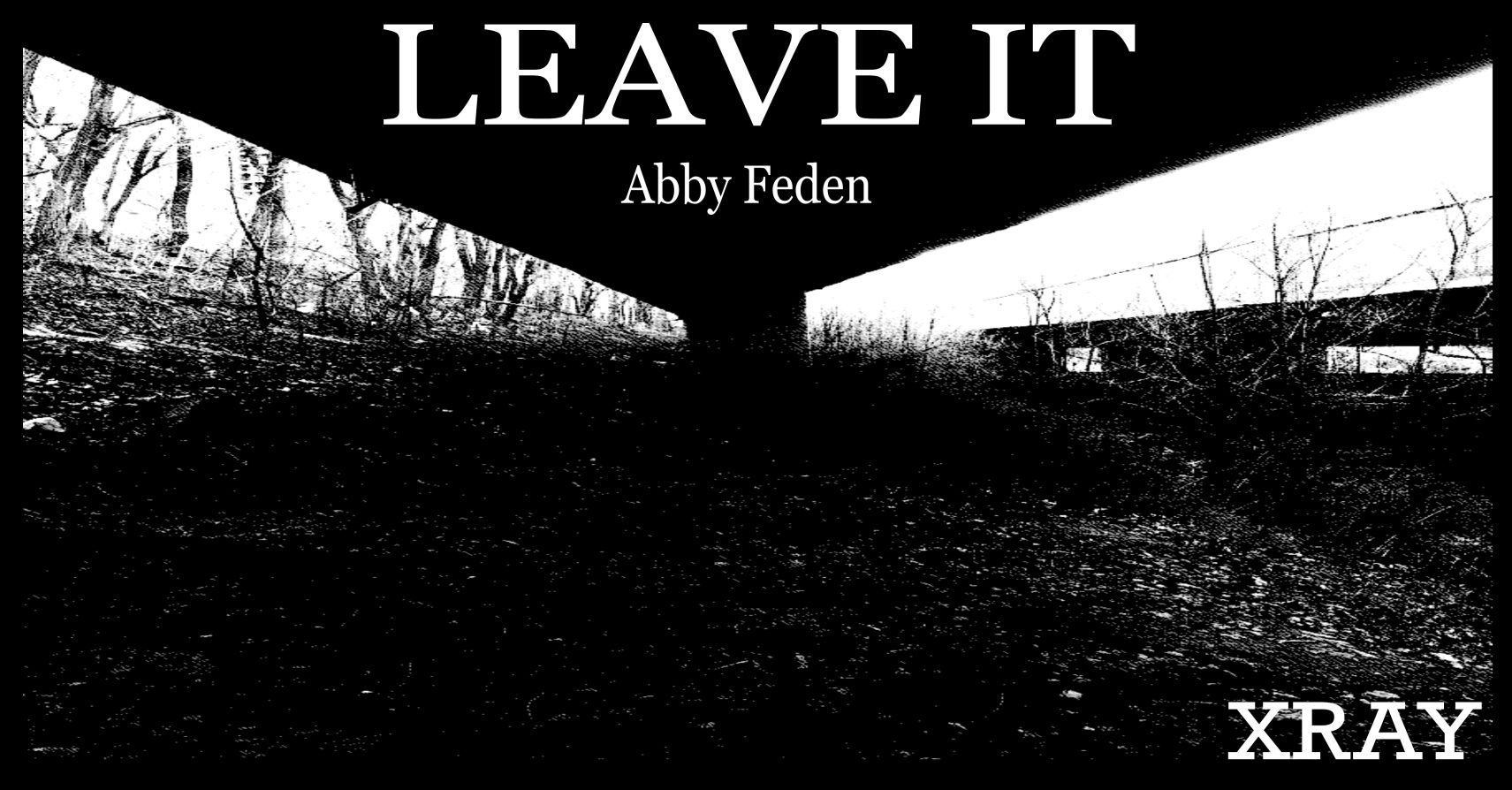

When the calf came fully into view of our tube group everyone groaned. The calf was upright, dead, legs fully swallowed by river mud. The velvet of its hide was kept by bacteria in the water. Flies hummed sweetly on its eyes and ate their fill. The calf’s tongue was the color of pink, secret skin.

On our float date, I watched my editor when the cow appeared on the horizon. She didn’t notice it at first. And when she did, she echoed me from that first calf trip, “A tree?” No, not a tree. I shook my finger in what I felt was a very sultry swag. “Just wait.”

People stopped coming to Calf River for float trips because the water level was lowering and the calf made them feel bad. I tried to make my own float group but I didn’t know anybody. My fellow newspaper carriers eyed my sunburned body warily and wanted their afternoons free. The farmers in town went quiet and sad at my suggestion. They did not like to think of good meat spoiled. I left notes around my paper route but my boss caught wind and wrote me up. I hung fliers up on the street and got a few tourists, a few teens, but the tourists didn’t want to look at the cow and the teens threw rocks and both of these things made me sick inside my tube.

I couldn’t bear to see the calf alone. I tried it once. I put my tire in the river and held my beer to my chest. But as the calf came into view, I began to doubt myself. I wasn’t sure how to acknowledge the calf as I floated by it. Should I say something? Should I stop and stroke its head? I tried to put myself in the calf’s position which was not very hard to do. I liked existing in peripheries. I imagined myself stuck deeply in mud and drowned and decaying but still there, still part of the river. I imagined the calf in a tube, bobbing down the banks to see me, but I had trouble imagining past that point. In my head the calf asked me what do you want and instead of answering I asked him the same question. Together, we shrugged our rotten shoulders. In the end, when the calf came up on the horizon, I couldn’t think of anything important enough. I got out of my tube and dragged it from the water.

I walked my way home.

When the editor and I made it to the calf, I was surprised to see how thoroughly it had rotted in my absence. The innards had ripped through the soft lining of its stomach, dried black with old blood and partially consumed by some violent prairie thing. The eyes were gone and the sweet tongue too. The sleek, baby spots of its hide had been bleached bone white by the sun and hurt to look at. But the thing stayed balanced on its little bowed legs. Still forcing itself into the land, the life around it.

I turned to the editor and smiled and did an exaggerated ta-da! and was shocked to see her sobbing.

“Oh God,” she kept whispering, “oh God.” She held her mouth open with the audacity that accompanies real pain. Her grief, forced onto me, the calf, the river around us.

She tipped out of her tire and ran a silly, watery run to the calf. She began to claw at the hardened clay around the calf’s legs. Some of the mud gave way and the calf shivered, threatening to collapse in on itself if any more was taken from it. I felt real fear then. I felt myself tip too.

I launched myself onto the editor’s back and my dead weight pulled her down into the water where I held her, only for a bit, until she stopped flailing. She emerged from the river so terribly, terribly sad.

“We have to bury it!”

She was in anguish. I was too. Just that morning, she had shown me a secret. A small ad at the bottom page of the classifieds offering a stack of rare dishware for a very good price.

“It’s my ad,” she told me, “but I sold the dishes long ago.”

I didn’t ask her why she kept the ad up because I already understood. Or at least I thought I did. I thought we were the same, each with our own quiet ways of being known. I felt betrayed by my editor. I felt deeply alone.

“We have to leave it,” I told her.

She tried again to move beyond me to the calf, but I took her bottle of sunscreen and upended its contents into the river and she left. I heard her crying even after she was long gone.

I stayed by the calf and took wet river mud and built back up the cast around its leg. I felt its nose and it was the softest thing I’d ever known. I took a nap in the shadow of the calf and when I woke, the sun was setting. The prairie echoed with summer sounds and the distant whooping of float groups on other, fuller rivers. The calf and I answered the sound with our own hollers. I thought about the editor’s classified ad, a papery, outstretched palm, and decided to stay the night with the calf instead of running my route. I imagined the editor spending the day sitting beside a silent phone and felt a great deal of peace.