After a year of research, and with my adopted parents’ blessing, I find my birth mother two states away. We meet at a dingy coffee shop in a mall abandoned by a cowardly Sears. She has reluctantly acknowledged that she is my birth mother, those words a sour piece of hard candy in her mouth. She is older than I expected, and frail, with a missing tooth and dyed red hair she must have tried to match with something she remembered.

Her speech is halting. She bags groceries at Piggly Wiggly and it’s hard on her hands when her arthritis acts up. She might smell like vodka. I came prepared to hate or love her, but I didn’t expect to pity her. She doesn’t ask me any questions, but supposes I want to ask her about the ‘doption. She says there is more to the story, that she will introduce me to someone, then stops as if consulting a schedule.

“Can you make day after tomorrow,” she says, peering around. “Here.”

I expect the “someone” to be my father, but surprised they’re in touch.

I return to my Motel 6 and tell the desk I will be staying a few more days, and that the ice machine isn’t working. My boss at the showroom is fine with my delayed return. I buy a pint of bourbon and return to the town’s diner for its daily special.

The next day, my birth mother dies in a freak elevator accident that, due to the odd circumstances, makes the local news and a front page story in the town’s newspaper. Rather than “the elevator victim” the failed elevator gets most of the coverage. There is no obit.

*

The two funeral parlors in town don’t have any bookings for “the elevator victim.” The town’s morgue sends me to the pauper’s crematorium. They actually say “pauper.” I find the redbrick building on a back street beside a car wash and park my rental car off to the side, wondering what to say. Can I say I’m here to see if anyone appears to claim the elevator victim’s ashes? It doesn’t feel right.

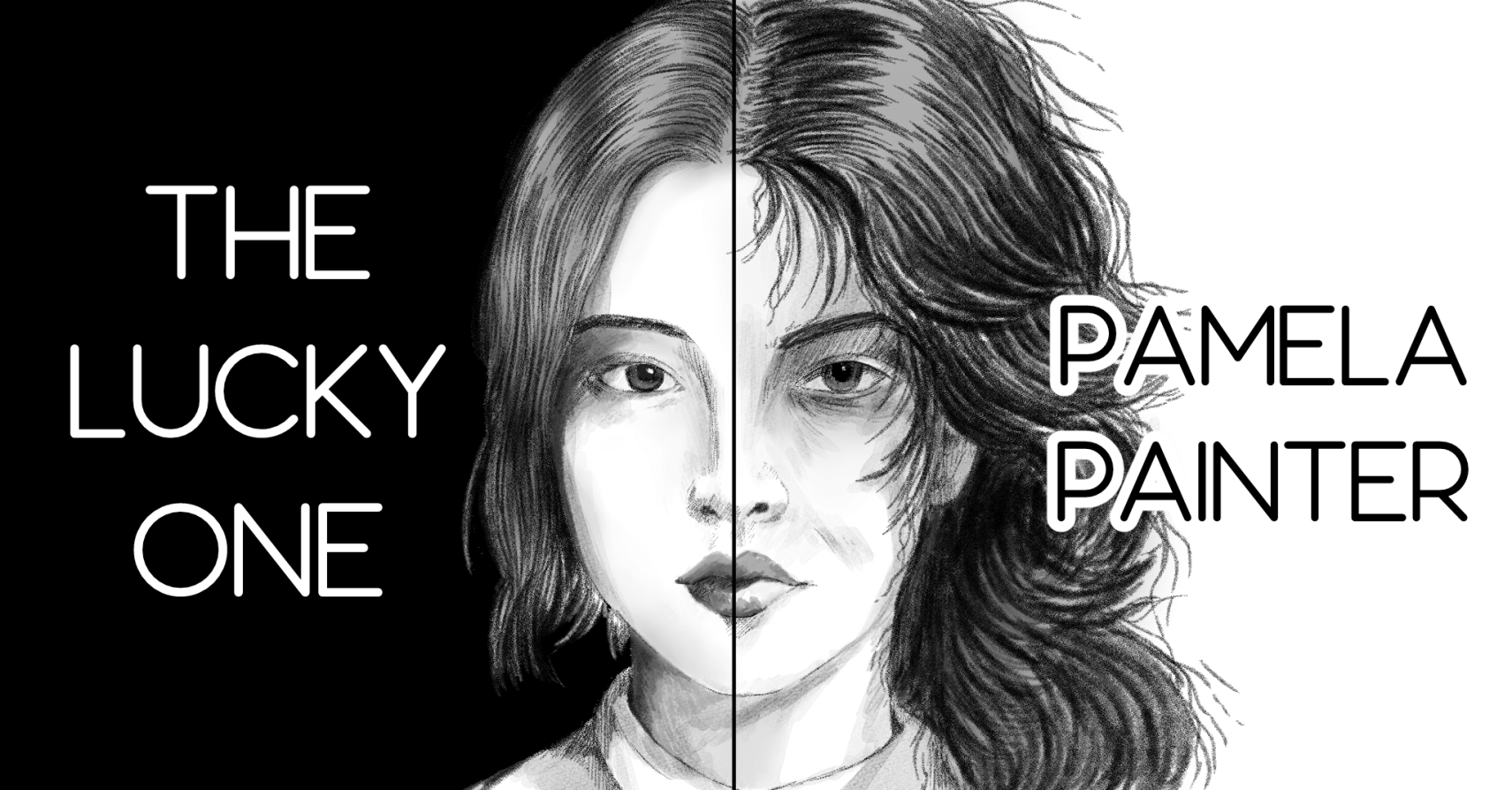

I enter the lobby. It turns out I don’t have to say a thing. This is when I discover I have a twin sister, a baby my birth mother kept when she gave me away. My twin has the same red hair and pointed eyebrows, the same overbite but left uncorrected. My twin is holding an urn–a cheap plaster container–and squints at me before slamming through the door.

I follow her to blurt out, “Our mother kept you and gave me away.”

She walks with purpose over to a gangly tree and dumps our mother’s ashes at its base, then smears them around with the toe of her purple sneaker. Then she turns to face me as if to see if I’m going to object.

“Yeah, I know who you are. You were ‘dopted,” she says. “You were the lucky one.”

That afternoon, Verney and I sit in a booth at the back of the diner. The waitress greets her and stares at me.

“Get on with you,” Verney tells her, not unkindly.

The coffee is burned. The Special hasn’t changed. In the next hour, I hear the story of their thirteen moves in nineteen years. Our mother a serial recovering alcoholic. No culinary skills. No father. Three stepfathers, one in jail. No high school diploma.

Verney says, “But last year I got my GED.”

She has a job at the Piggly Wiggly just like her mother. But she’s head cashier.

She says, “I’ll make manager this coming year.”

All this compared to my four-bedroom, two-bath home. A mother who’s a librarian and a father who doesn’t drink, prepares people’s tax returns, and taught me how to swim. Friends, boyfriends, piano lessons, yearbook editor, college. My job at Design Reach. I hurry over these details of my adopted life. I fish for more details of her real one, but my twin doesn’t have many more.

She says her shift begins at Piggly Wiggly in an hour. She says my name. O-liv-i-a. Olivia. We write our phone numbers and addresses on paper napkins. Her pointed eyebrows rise to learn that I live two states away. We sit a moment longer, perhaps wondering if we can make up for lost twin time. The waitress is nearby filling salt shakers. I put a credit card on the green tab, and then exchange it for a twenty. Verney rises to leave with someplace to be.

“Pleased to meet you,” she says.

“Me too,” I say. “Maybe I’ll come back sometime. Not too soon.”

“Sure,” she says.

She stares at us in the booth’s foxed mirror. Two red-heads at lunch.

“We could be twins,” she says, and laughs. Then says, “It don’t make sense.”

She shrugs and wiggles her fingers at me, nods at the waitress, then she is out the door. She doesn’t cry. I cry.