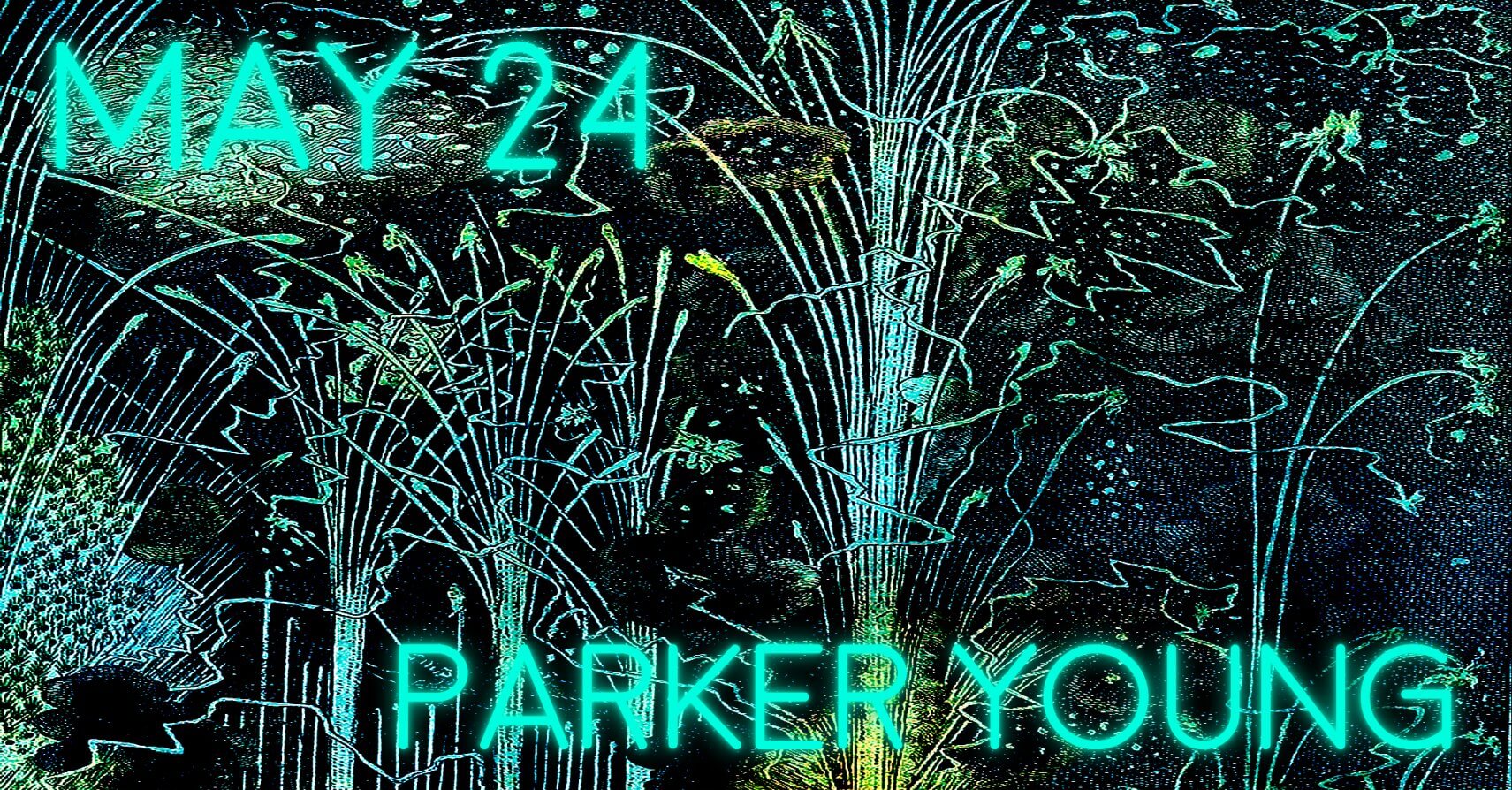

At some point, I don’t know why, I decided I would write a novel about May 24. Whatever happened on that day would dictate the content of the novel. I was a novelist who had never written a novel. I thought it would be easier, instead of going out in search of a novel, to let the novel come to me, like a day on the calendar. It was a day on the calendar, nothing more or less, May 24, impossible to rush or delay. Then the day arrived, May 24, and nothing happened. I should have expected it. Nothing ever happened, but I think it’s fair to say that even less happened than usual on this day, the day of the novel. I was supposed to go out with several friends—they knew about the day of the novel—but they all canceled for dubious reasons. They might have been nervous about their capacity to fill a novel with subject matter. I tried to assure them that content rarely matters. It was a lie of course, because content is everything. In other words, style is everything. Because content is style. But they didn’t read novels, so they couldn’t tell I was lying, at least not right away (on the other hand, a novel really can be about anything as long as the writer has a sense of style… which is to say content). Then, at the last minute, they canceled. I hadn’t really expected them to act naturally. In fact, that was what I’d been planning to write all about: how unnatural my friends were acting because they anticipated being novelized. A meditation on our inability to transform ourselves in our daily lives in the way that the artist transforms her subject matter. Now that my plan had failed, I realized this would have been a terrible novel, an immoral catastrophe, because the only person spared by this literary examination would have been me, the writer—if the book existed, there would be no getting around this damning conclusion. It would have been an evil book about the writer’s supposedly superior means of moving through the world, transforming mundane experience into high culture, and I would have been forced to renounce it eventually.

Still, it was bad that nothing happened, because inside every novel there must be something. Even a man sitting in a chair, thinking; that’s something. Therefore, it’s misleading to say that nothing happened on May 24. When I thought about that—how even nothing happening is just a way of describing something happening—I became hopeful. I thought maybe I could write a novel about nothing, that is, something. Well, I thought, what’s happening? What’s happening right now? Unfortunately, what was happening was I was thinking about what was happening. I was applying the writing process to the writing process, and all those layers of removal created such a sense of vertigo I almost collapsed. I felt physically ill. My heart made a squelching sound in my head. This was why I needed my friends to appear, so that writing about writing wouldn’t be completely unbearable. On the other hand, if they had appeared, I would have used them in the most monstrous way imaginable, like puppets.

In order to write, I needed the writing process to disappear. But without the writing process, obviously I wouldn’t be a writer. For some reason, I couldn’t accept this, the idea that I wasn’t a writer. At the same time, I couldn’t accept the writer’s duty, which is to write about writing. For the writer, there’s nothing else to write about. If the writer illuminates some other topic, it’s only an accident. Perhaps, I thought, the good writers are those with a tendency to involve themselves in such accidents. But because it’s always an accident, it’s not something they should take credit for (which never stops them from doing so.) Can you cause accidents on purpose? Maybe, with experience, you could learn to cause accidents. Unfortunately, I didn’t have experience. I’d never written a novel before. All I had was this date: May 24. And the events therein. Which amounted to nothing. Nothing but writing. Then a miracle happened. I died in a traffic accident.