Michael, who stayed posted out front of Walgreens, requesting eats from entering and exiting Walgreens customers, was presently posted out front of Walgreens, requesting eats from entering and exiting Walgreens customers.

“Yo what’s good,” I said as I approached, timing this utterance and my gaze, should he choose to reciprocate either, with the moment we crossed paths, so as to avoid a prolonged interaction.

Michael averted eyes and seemingly deliberately pretended to not see or hear me. Kneeling, he adjusted the Velcro on his foot brace, through which his enlarged, pale, callused toe was visible.

Once past the San Pablo X Ashby bus stop and around the corner, shortcutting through the gravel that hypotenuse-d the sidewalk’s edges while scanning its surface, in the fluorescent Walgreen sign-light, for dog or human shit, I said: “Damn, that was cold.”

Rosie remained silent, head bowed, hair shadowing the right side of her face. Ten-or-so paces later, she said: “He’s probably just embarrassed is all.”

I considered this. Then said: “Huh. That never occurred to me. You’re probably right.”

#

While we, Michael and I, were by no means besties, our repartee did go back a ways:

Michael slept outdoors; I was frequently nocturnal and spent much of my nighttime hours outdoors also, either to smoke strolling up and back Ashby, or on a bench on Ashby, or on the back bumper of my van once I secured a parking spot out front the apartment; or else to or from my van which, until the spot opened up about three months into Rosie and my year-long lease, I’d park on some shadowy one-way or dead-end in a five-to-ten block radius of our apartment.

He’d ask for cigarettes; I’d always have cigarettes, and would always give him one, even if I had to roll it for him.

We knew each other by face and, in his case, by the stimulants I could be counted on to be holding.

#

One night he knocked on my door—the back door, on the side abutting a ’bando, that tenants less frequently walked down—to ask for a cigarette. He was clearly lit—I could smell it, plus he had an open forty in a paper bag right there in his hand. I was decidedly not about him encroaching on my allotted space like this, but happened to be going out for a cig anyways when he knocked, not to mention had just toked the one-hitter so was feeling receptive and open I guess. We ended up smoking two cigs consecutively out back of my apartment, the furthest off-street of the four comprising the first-story of the eight-unit complex that, on first glance, most resembled a seedy motel.

Adjacent to the complex’s collective dumpster, our unit’s back wall was bisected diagonally by a stairway leading to our upstairs neighbor Olaf’s; beneath the stairway was a large, maybe ten-by-six-foot—just about wall-encompassing—window, which at its lowest point was low, say two feet above-ground, and had, on either end, matching, two-foot-wide slot windows that opened sideways, like doors do, operated by a rotating handle. At least one window was generally left ajar at minimum a cat’s width when one of us, Rosie or I, were home, so Winnie could come and go at will; and the blinds were generally pulled up a foot or two since if they weren’t, Winnie would be sure to paw at them repeatedly until one of us (meaning me) lost their shit.

#

But we were back there smoking, and Michael was just going in, rambling about this and that. I learned that he was good homies with the previous tenant of the apartment we lived in. I learned that the previous tenant had lived in the apartment for ten, twenty years, and had died, presumably in the apartment, just months ago. Months before we moved in.

“For real?” I said, feeling like someone, our landlord or neighbors, should have told us about this by now.

“Oh yeah. George lived here forever. I used to, uh, I used to come over and he’d give me food, help me out.”

“Word,” I said, understanding a little better now why he thought it kosher to knock on my door, if still, ultimately, not about it.

The blind ruffled. I looked over and saw Winnie’s head poke through, before retreating back inside when she saw me. Or likely when she saw, or smelled, Michael.

“Yo, how’s your foot though? Getting better?” I asked.

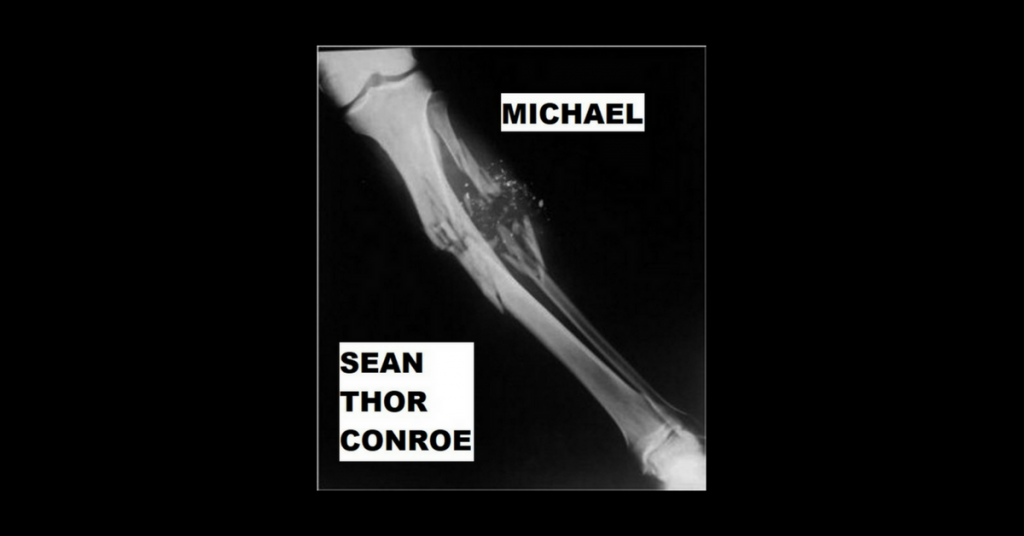

It wasn’t, nor would it. It was initially injured by a cop, who ran over it, either accidentally or not unclear. When it didn’t get treated, it turned into trench foot, and had been in this enlarged, damn near ossified state since.

Michael asked what I was about. I told him I made coffee and wrote some.

“Man, I need someone like you!” he said. “I need someone to write my story. I have the craziest story, just crazy, but I don’t have the time to write it down.”

“You don’t have the time?” I asked, laughing.

“Naw man! You see me out here, just trying to get by.”

“OK, I feel you,” I conceded, nodding.

When I finished my second cig I dapped him up—his hands were so leathery they felt fake, like prosthetic, or like tight-fitting leather gloves—and watched him shwhip it away, tottering, on the much too small Huffy he showed up on.

This must have been in January.

#

Weeks ago we’d gotten hit with a bout of nonstop rain, like the East Bay can produce periodically, just to keep its meteorologically spoiled inhabitants in check. It was one of my days off, I’d slept all day, woken up shortly after Rosie got home from work. She was fixing herself a salad in the kitchen area, listening to a podcast on her phone. It was dark out.

“Really coming down, huh,” I said.

Rosie, who still had her button-up on, made a gesture to the window like Go look. Confused, I went to the window, started to open it. I only rotated the handle maybe twice before I saw something was off: there was a pile of what appeared to be clothes, wait shoes—

Michael.

Homie was straight up passed out basically beneath our window, his head wedged into the lowest couple steps of the stairs leading to Olaf’s. The left side of the faux-leather couch we had in our living area was pressed up flush against the window, and I generally sat right there nestled against it, so as to be able to exhale THC smoke directly outside without having to get up, or activating the smoke alarms.

At first I did nothing. Rosie left to go on a grocery run, came back, took a shower, went to sleep. I took a shower, made food, got dressed, and went out to work in my van for the night, figuring he’d be gone by morning. When I got back around 3 a.m., however, he wasn’t. I smoked my hourly cigs until sunup on my designated cinder block pretty much right next to him.

But it kept raining.

And Michael came back the next night.

On the third night it was only somewhat raining, was on and off, so Rosie let Winnie out, at maybe 7 p.m.

Winnie had an ongoing beef with this dog in an adjacent lot and would often disappear through this crack in the fence, sometimes for hours. She was by no means an outdoor cat though: her fighting technique consisted of lying on her back and swiping lamely at her attacker, and she’d sometimes come back with scratches on her belly.

I went out for a smoke at maybe 8:30 p.m., with my headphones in, and damn near sat on Michael. I was like Bruh—I said, “Bruh,” out loud—but he didn’t budge. I knew he heard me though, because he burrowed deeper into his jacket and grumbled like a kid who didn’t want to get up for school. Like I was the mom.

I finished my smoke, headed back inside.

The rain started coming down harder. An hour, two hours passed: still no sign of Winnie. I posted up in the living room, worked on whatever it was I was working on, glancing outside to see if Winnie was out there—opening the front door for stretches in case she wanted to come in that way. I made all the sounds I could think to make that generally made Winnie come a-running. Nothing. All I could do was hope she’d found some awning or Totoro leaf-umbrella beneath which to take cover (although she did have fur, I reasoned).

Come 3 a.m. I’d had it.

It was time to re-up on coffee anyhow, so I put two cups’ worth of water on the stove, scooped generous spoonfuls of Maxwell House into two mugs, added sugar, then near-boiling water, to each, stirred, and went outside.

The rain had subsided somewhat, it was heavily misting at this point; and the air, even at this ungodly hour, was warm and dank.

“Yo,” I said, whispering.

Then: “Michael,” louder this time.

Nothing.

“Ayo, Michael,” in a conversational tone.

Before finally: “BRUH!” damn near yelling.

He jolted awake.

“Listen, you gotta make moves, bro. Hate to do this but you can’t sleep here, you’re fucking up my shit. My cat’s been gone like ten hours now, and you’re blocking her path home.”

“Huh?” he said, trying to do the thing where he burrowed deeper.

“Nope, don’t do that bro,” I said. “Here, hit this, it’ll make you feel better.” I handed him the coffee. He sat up. Took the mug, downed it in four gulps, spilling some on his chest. He ahhh-ed. Belched.

“There’s gotta be a shelter,” I said, pacing. “How the fuck is there not a shelter?”

Michael looked at me surprised, and handed me the empty mug, before saying, “There is. It’s just far.”

“What about those trees by the Aquatic Park? By the tracks? If you get a tarp—. Like, I just can’t have you—”

“I know, I know, I got it,” he said quickly, like he’d been through this before.

Gathered himself, put on his hood, and stumbled off into the darkness.

Five minutes later, Winnie jetted out of the gap in the fence and booked it back through the window. She was sopping, meowed loudly at me in a way that sounded eerily human-like, and sprinted under the bed.