Translators’ note: In Hungary, elementary schools all have singing classes. Older women are addressed as “Aunty”.

The oven was ticking, the electricity was out. The fridge sighed deeply as if relieved by the brief power outage. Then as soon as the outage came, it left. The digital clock on the oven was blinking again, the fridge’s compressor started up with a rumble, the internet connection came alive.

Within seconds there were indignant complaints appearing on the village’s Facebook page. How many power outages this week, on which streets and for how long, and who was inconvenienced by it? “Power outage in Ibolya Street. I’ve had it up to here”, Aunty Gabi wrote. The three moving dots suggested that someone was commenting. “When is the village council going to do something about it? Chopping down trees is not a solution!” This was written by Aunty Gabi’s neighbor who lived right beside her Ibolya Street house; but they preferred communicating via Facebook. Since March, Aunty Gabi has been giving her elementary school singing classes from home. Her neighbor resisted having the electricity company prune the branches of her hundred-year-old walnut tree, which — the company said — caused the power outages.

One time, when Aunty Gabi was jogging with me from one end of the village to the other, she said that she no longer cared. She had given up. Back in March she still considered herself a kindly teacher who liked her students; it didn’t bother her if some were tone deaf, as long as they were keen and prepared for the class. She mentioned my niece who sang the first and second verses of “Under the Mountains of Csitár” painfully out of tune, but at least she knew the words, and that was enough. But ever since the whole school switched to online learning, she hates the kids. They are unruly, cheeky, and never do their homework. I didn’t tell her that my niece gave the same assessment about her; to be exact, she said that Aunty Gabi is totally useless and there is no need to prepare for the singing class because Aunty Gabi’s internet will go down at least three times.

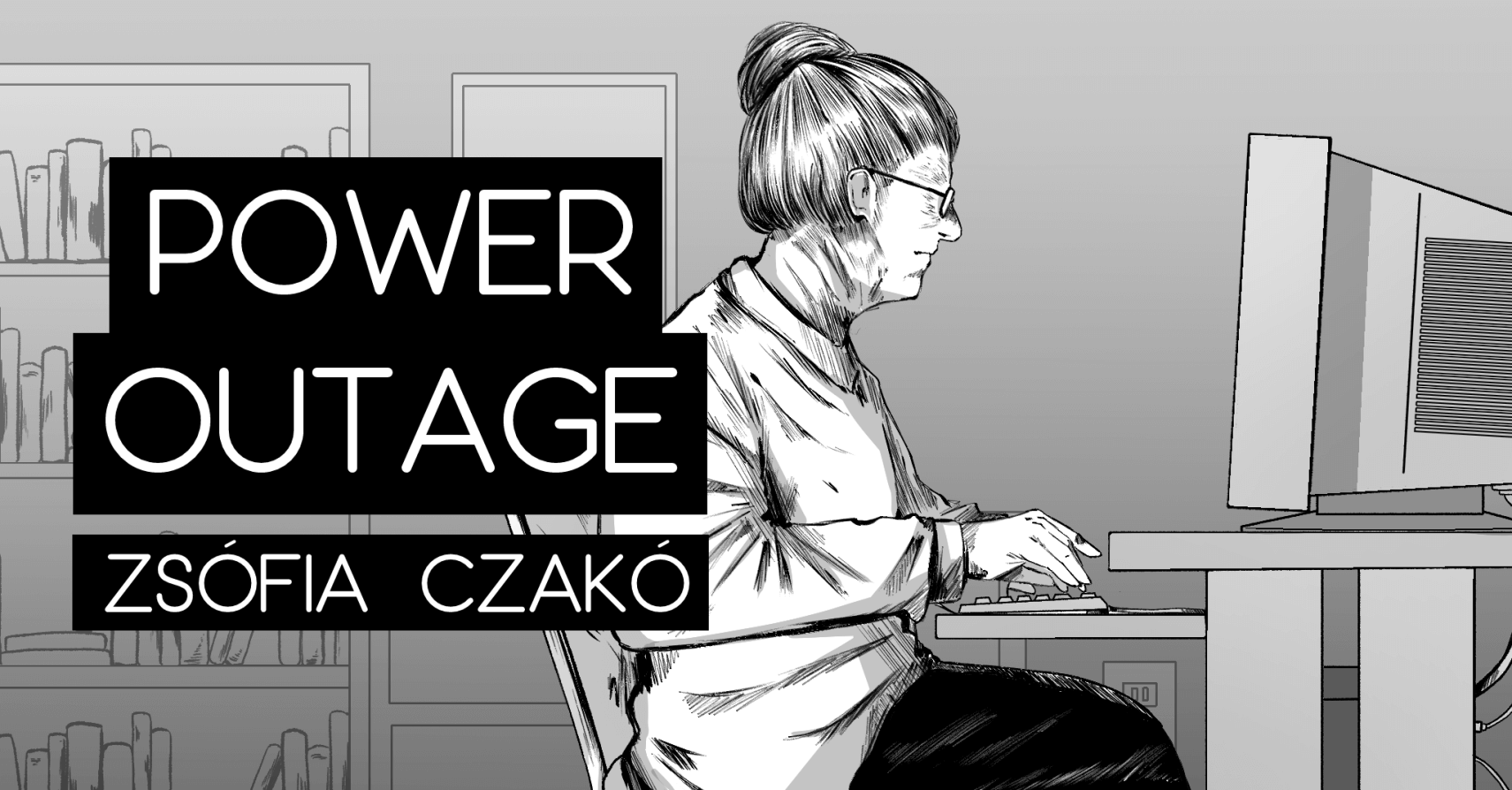

After the run she invited me to her place. I was given a glass of water and some grapes, and I had a look at her neat garden and her pretty, orderly house. Of course she also showed me the neighbor’s walnut tree. She looked at that tree as if it were a murderer, and with hate in her eyes told me that in her dreams every night she sneaks over with an axe and chops it down with two strokes. The kitchen and living room were joined together, and the old computer on the table was making a loud whirring sound. She hadn’t needed a computer at home until now. She used textbooks to prepare for classes and, besides, she said, after forty years, the preparation needed was mostly psychological. When in March the village school closed down again, her son brought over the computer from Budapest that was bought for him when he went to university twenty years ago. He showed Aunty Gabi how to use it, and at the age of sixty-two she didn’t even find the machine very challenging, except that it was slow. If her first class was at eight in the morning, she turned it on at seven and waited for the hourglass to finally turn into a cursor, she clicked on the icons, took out her notes, and got the material ready. That takes me quite a bit of time, she said while washing the grapes in the kitchen. Her movements were not rushed. She was calm and deliberate, clean and neat like her home, the pleasant harmony of which was only spoiled by the machine’s drone. She prefers to leave it on to avoid waiting for it to boot up. At the beginning she didn’t send out the material in a printed form because she figured that the kids had the book at home, but when during the online class she asked them to take out their books and turn to page thirty-four, no one budged, as if they had no idea what a book was. Because of that, she had to do copying as well, and that could only be done in the city.

One evening my niece stayed overnight. The next morning she signed in for classes from my computer in the kitchen because her phone battery ran out while watching TikTok videos. The day started with the singing class. When she got up at 7:50 she said that half of the pupils wouldn’t show up on time because Aunty Gabi is totally useless and her computer is so slow. Aunty Gabi was indeed late; by the time she signed in the kids were discussing something that had happened on TikTok, talking over each other. It took her a while to control the class, and she had to order them to pay attention by using louder and tougher language. My niece turned off the microphone and laughed. After a lot of effort, Aunty Gabi gave the starting note and started singing “Forest, forest, forest, Marosszék’s big dark forest”. I went to the kitchen to prepare breakfast. My niece became enthused, and she lustily let loose her out-of-tune voice with “I would give sugar to that bird”. When they got to the end of the folksong, Aunty Gabi started out again “Forest, forest, forest…” and I was about to sing along as well but when they got to “My perky little sweetheart” the connection was lost. The oven was ticking, the electricity was out. The fridge sighed deeply and everything turned quiet. I seemed to hear, from Ibolya Street, Aunty Gabi screaming and the wind whistling and tearing at the dead branches of the old walnut tree.