If there’s a poet laureate of contemporary humor, it’s Brad Neely. The George Washington rap. Wizard People, Dear Reader. Baby Cakes. The Professor Brothers. China, IL. Neely’s idiosyncratic voices, bratty poetics, and ecstatic profanities often punch up at institutions and powerful figures, and punch across at the absurd things we and our fellows say and do. Now he’s punching a Civil War hero.

If there’s a poet laureate of contemporary humor, it’s Brad Neely. The George Washington rap. Wizard People, Dear Reader. Baby Cakes. The Professor Brothers. China, IL. Neely’s idiosyncratic voices, bratty poetics, and ecstatic profanities often punch up at institutions and powerful figures, and punch across at the absurd things we and our fellows say and do. Now he’s punching a Civil War hero.

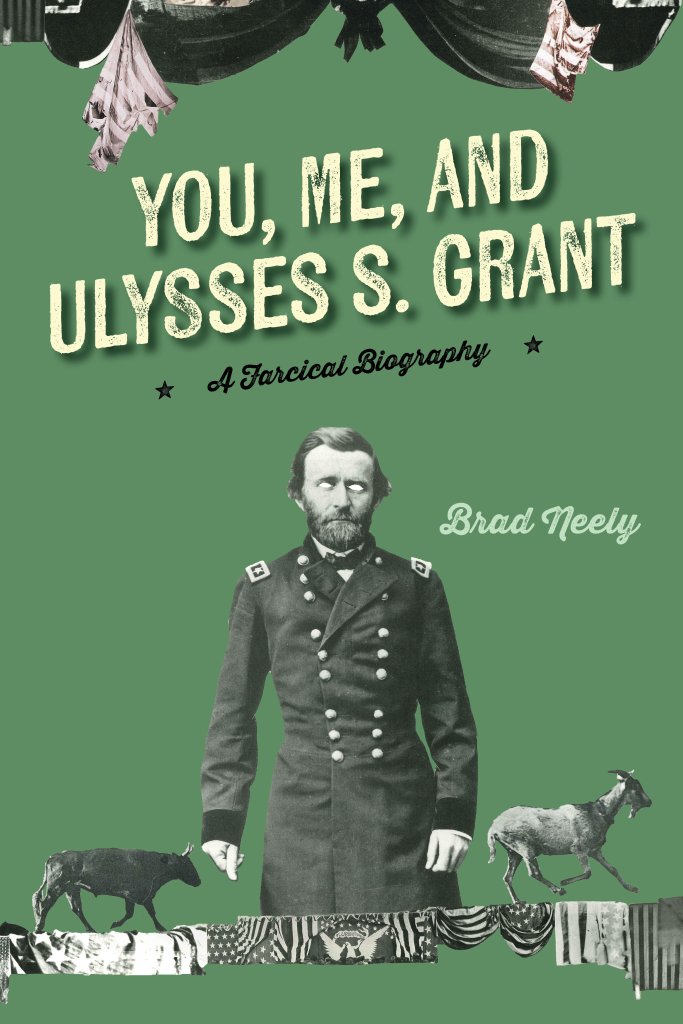

With his new book, You, Me, and Ulysses S. Grant (Keylight Books, 2024), Neely points this humor at the hero-mythos around Grant, looking for the complicated, filthy human beneath the gleaming myth. Over email and video chat, we talked parasocial relationships, the hero-worship-to-cult pipeline, and whether relaying someone’s life story within the limitations of narrative structure is ethically responsible!

Sarah Lyn Rogers: I’m interested in this book’s title—not just “Ulysses S. Grant” but You, Me, and Ulysses S. Grant—which reminds me of the “Dear Reader” in Wizard People, Dear Reader. Both texts directly address the reader, giving the narration a conspiratorial, inside-joke-y vibe. Who is the “You” that you wrote this book for? Do you imagine a specific archetype of reader as you write? Or is this more about the connection that all stories create between an author and a reader?

Brad Neely: “Yes” to all the answers in this question bouquet. I think reading can be so intimate. It is an invitation to be part of something that requires a “you.” I wanted to explore the subjective nature of writing and of reading about an actual person who once lived. It’s kind of strange that at some point only the reader will be the one living. Right now I live. It’s you and me, living, thinking about this dead person.

I wanted to be overt about my desire for the reader to imagine being in the life and times and body of this person. The book is very much about people being with people in the present moments, being with another body, and how we communicate without words with our bodies in shared space and time. And I wanted to highlight how that’s an impossible fantasy in biographies of someone in the past for people like us in the present.

That said, I wanted to be silly with the title, to signal the kind of comedy to expect in the book, which is often at the expense of the author’s lack of tact or grace or awareness of how things are usually done. It had a kind of childish naivety that I liked, but it actually served to T up the themes I tried to bake into the book.

SLR: And who’s the “Me” in the title? Is it you? Or a version of you?

BN: That is Darby Elen, one of a few versions of myself that I use when writing. Darby was the same persona I used for Wizard People. It’s me, and it’s not. He’s less careful and less aware than I try to be, though I’m sure he’d say the same for me. I give Darby the projects that need a flawed narrator who loves the subject so much that he exposes problems with loving it. He doesn’t understand the assignment and just makes it all about himself. Which is what I feel we all do to greater or lesser degrees. In this book he’s a bad biographer/historian. And the book was my way of wanting to poke fun at all the biopics and historical fiction out there masquerading as rigorous truth.

When we tell stories about actual historical people, we fall into these narrative traditions where we know we’ve got to have a theme, and act structure, and all of these storytelling tools to get people to stay on the hook while they read. I think that conflicts with being truthful to how things really went. It’s wise craftsmanship, but whether it’s philosophically ethical is another question.

SLR: That’s really interesting. And Darby Elen! I’m so glad I asked. Do all of your personae have names?

BN: I have five or so main names, all scrambles of my own name, that range on a scale from realism, to melodrama, to comedy, to farce, to experimental, to dada. Darby is in the farce zone whereas Eel Brandy is way, way out there.

SLR: Let’s talk about hero myths. You’ve written and/or sung about the fearsome George Washington; robot JFK; and Harry Potter, a “near perfect new god” who is also “drunk every day before noon.” Now you’ve brought us Grant, hero of the Civil War, but who just years before that victory had little to show for his life, and at forty years old, was “technically already dead.” You seem interested both in inflating the impressiveness of a myth beyond belief (maybe poking fun at myths themselves), but also in reminding us that heroes are just people, with flawed judgment and meat-bodies, like all of us. Tell me more about this quote from the book: “Wanna keep your heart unbroken? Remember there are heroic deeds, not heroic people.”

BN: Yes, again. Thank you for understanding me. In a novel I felt I could go big, into abstracted myth, but I could also do quasi-3D things with Grant on a human-being level. He had a life that just cried out to me. I felt I had a lot in common with him, for better and worse, but certainly on a minor scale compared to him. But, yes, I think hero worship leads to cults and cults are gross. Trump is gross and his cult is gross. It’s embarrassing and immature, all the hero worship. That said, I do it. We all do it. And love is powerful. Love can get us worshipping.

When we shape a hero, even when it’s someone who existed as a person, we represent them in the emotional bath of ourselves. We make them out of our experience pool. We throw this word “empathy” around today like it’s just a given. But if you walk a mile in another person’s shoes, the first thing you realize is they’re not your size.

I also hate revisionist history. I hate political spin. I am very big on uncertainty. If you’re not there you can’t really know. This book is an exercise in Presentism and Fallibilism. I’m concerned and amused with how humans can fail. False positives and false negatives are my little shoulder demons. Doubt is an angel to me. It’s improbable that anyone represents anything exactly accurately. Add time and space and it gets harder. Compound the subject and it’s harder still. But we can’t forsake the good for the perfect just because humans can’t ever achieve (or confirm) any 1:1 to complete objective reality, be it past, present, or fiction. But that doesn’t mean we give history up wholesale. I think objectivity is a scale, and many are on the loose side but claim otherwise.

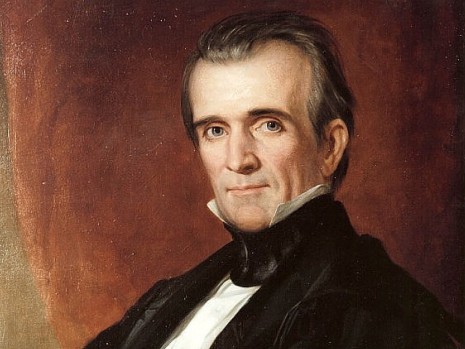

SLR: Be honest: Who’s the hottest president?

BN: There are a lot of fun ways to answer. Technically, literally the hottest is the most recent in terms of climate heat. Biden is hottest on record anytime he’s outside. But I know this wasn’t what you were asking.

Ranking physical attractiveness gets into a favorite theme of non-firsthand evidence. Polk is the cutest, but we have only paintings of his early glory. And he lived in a stinky time and I’m an all-senses-must-agree kind of guy. So again, we gotta get contemporary to kill the smell. Biden probably smells like vitamins and medicine. Obama you know smells great and probably has a scent brand “collab” with Netflix. Trump smells like dump, like all that compacted McDonald’s and burnt ketchup. Plus, he’s an oaf. Ugh.

Reagan was a pomade jellybean. Reagan was a sugary tar pit grandad crocodile, with skin quavering in the shade of the Berlin Wall before the sun broke through and melted his petroleum hair off his deteriorating skull. Not hot. He ruined so much, the fucker.

I know Clinton is a no-go for anything positive, but before we all knew everything about him, I was a teenage Arkansasan seeing an Arkansasan running for president on MTV taking questions from teenagers. When he was asked what his favorite authors and artists were⎯and I may have altered this because these are some of my diehard faves —he said Borges and Rodin. A southern accented aesthete is irresistible to me. But alas, et tu Billay? (I said this in the Forest Gump voice)

FDR and Lincoln are a tie, and I’d just hold my nose.

SLR: Lol at “Biden any time he’s outside.” With you on Lincoln. Those cheekbones could cut glass—he’s what the crystal girlies might call “gemmy.” It seems like you had a lot of fun describing Grant’s physical appearance. (At one point he was so thin that the seam of his pants “ran directly across his anus.”)

BN: Thank you so much for saying out loud a line that runs directly across my mind’s eye all the time. I got to say all my little things in this book. I love descriptive language, and I hate it. The thought of being depicted is a personal nightmare. Yet, Darby has no qualms. Darby would write a one-thousand-page book of describing one person in one moment in time, and it would feel like a Christmas of a million little presents. At least to him.

SLR: I read that you’ve been working on some version of this book for twenty years (!!). I’m curious about anything that can sustain an author’s interest for that long. What initially made you decide to write a farcical biography of Grant and what kept the dream alive all this time? What’s going on between you two?

BN: I liked him right away. I felt his story was very much like the American stories of my friends and family. And me. Capitalism is “work or die.” “Provide or die.” We’ve all had to make decisions based on money. I saw his life as a string of sacrifices, or at least I felt Darby could see it that way. Darby sees his life mirrored in Grant’s. And I felt that such egoistic empathy would be seductive to a biographer, to get them wandering from their objective rigor. Anyway, my love for Grant gave me pause. I felt that inertia. To love your subject as yourself, to do unto your subject as you would have others do unto you… that could illuminate my gut feelings about empathy and our overuse of that word and how now we all feel like, with a little bit of empathy, we can know anyone. But we just end up making them into ourselves. The golden rule can be a trick mirror. “I get it! They’re just like me!” No, honey. No.

BN: I liked him right away. I felt his story was very much like the American stories of my friends and family. And me. Capitalism is “work or die.” “Provide or die.” We’ve all had to make decisions based on money. I saw his life as a string of sacrifices, or at least I felt Darby could see it that way. Darby sees his life mirrored in Grant’s. And I felt that such egoistic empathy would be seductive to a biographer, to get them wandering from their objective rigor. Anyway, my love for Grant gave me pause. I felt that inertia. To love your subject as yourself, to do unto your subject as you would have others do unto you… that could illuminate my gut feelings about empathy and our overuse of that word and how now we all feel like, with a little bit of empathy, we can know anyone. But we just end up making them into ourselves. The golden rule can be a trick mirror. “I get it! They’re just like me!” No, honey. No.

SLR: What was your approach like in writing this novel? Was it different from the shorter-form audiovisual work you’re known for?

BN: I always have a bunch of projects going at once. Lots that are decades old or more. And it’s for all types of art. Literature for me is a place of self-expression. It’s not about selling and entertaining a general audience. I feel that I can go as deep or as odd or as personal, as textual or subtextual, as highbrow or lowbrow. The biggest difference is that I’m a book guy and cartoons are more of a lucky fun hobby-job.

SLR: Talk to me about Horse Lord Weekly, the definitely real magazine that young Grant wants to be featured in. It’s such a funny running gag that also highlights the class hostilities we see throughout the book, with “the richies” always knocking Grant down a peg. You’re great at using absurd details and concepts to critique institutions, pop culture, and human behavior. What are some other useful fictions you planted in this biography?

BN: We all have these kinds of institutions hanging over our heads. The New York Times Book Review for me, right now with this book, for instance triggers my class resentment and desire to level up or toss shit. I think an underdog’s psychology is always funny in the insecurity. But yes, I made up quite a lot for this book. Lots of blending of facts with fun tweaks. I mean, there had to be horse books and horse journals, horse columns in the papers. Good horse writers. Horses were a huge part of life and status, just like cars.

SLR: You must have done so much research while writing this book. How did you decide which true details to keep and which to toss or transform? The battles read like prose poems, conveying the shape and feel of what happened; verifiable facts are threaded through surreal imagery and hilarious snippets of dialogue captured by some omniscient (omni-audient?) ear. The level of detail suggests way more detail. Was this book once an enormous tome?

BN: Thank you. Omni-audient is fun! Yes. This is a fraction of the facts. I did do a lot of research for me, but not enough to be considered factual or reliable. I just watched Turn Every Page and I’m in debt as much as we all are to the historians and editors of Caro and Gottlieb’s discipline. And even then, you see Caro agonizing about the narration of history. We say story is this magic thing, but we tend to forget that magic can trap heroes in the woods. This book was once too small. Then it got too big. Then it got just right. Just like the story of my body.

SLR: Dare I ask if, after working on this Civil War book for so many years, this feels like a weirdly timely…time…for it to be released?

BN: I worked on this book⎯mostly off, but occasionally on⎯for twenty years. I have hope for America, but you hear and read the words “Civil War” often in relation to current events. When I was writing I was watching as the confederate flag made its way into our nation’s Capitol on Jan 6th. That felt disgusting to me. After all the sacrifice. To just see that idiotic evil. I have no illusions about fixing things with this silly book, but I wanted to be obvious, I wanted to scream the moral clarity of freedom and equality and compassion. And I wanted to make fun of white supremacy. I wanted to highlight the fact that all of us are struggling under capitalism, but that we can’t find success by taking success from others. So unfortunately I feel reiterating basic morality will always be timely.

BN: I worked on this book⎯mostly off, but occasionally on⎯for twenty years. I have hope for America, but you hear and read the words “Civil War” often in relation to current events. When I was writing I was watching as the confederate flag made its way into our nation’s Capitol on Jan 6th. That felt disgusting to me. After all the sacrifice. To just see that idiotic evil. I have no illusions about fixing things with this silly book, but I wanted to be obvious, I wanted to scream the moral clarity of freedom and equality and compassion. And I wanted to make fun of white supremacy. I wanted to highlight the fact that all of us are struggling under capitalism, but that we can’t find success by taking success from others. So unfortunately I feel reiterating basic morality will always be timely.

SLR: Early in the book, the narrator (so: you, a.k.a. “Me”) tells us that “the American Dream is to survive the American Reality”! It’s something that feels intuitively true, but I’d love to hear more about that.

BN: I hate that there is no social safety net. I hate that medical care isn’t free. I hate that most people in America have multiple jobs but can’t make rent. Capitalism kills. We all know it. Everyone is forced to make appalling decisions in the face of making money. Imagine America if we took care of everyone. I like to think we’re working toward that.