THE INHERITENCE / LA HERENCIA by Sam Moe

I think we’re all stuck to the Manhattan apartment, its thick coatings of paint intertwined with our veins, which crisscross around the city, glowing in the night, fraying when we argue.

I think we’re all stuck to the Manhattan apartment, its thick coatings of paint intertwined with our veins, which crisscross around the city, glowing in the night, fraying when we argue.

But before I can swallow, I must disarm her. Rob her of agency and hope. Break the faith that brought her to the enclosure.

The more of Elaine he had had, the less it felt like she belonged to him at all. Besides, he said, I have learned that even possession is a kind of disappointment.

The couch is more of a loveseat. It hardly seats the two of us. On it is the pillow and blanket I’ve been using. This is the longest conversation we’ve had in over a week.

She’d say that it’s not enough for a man to create a life; he must sustain it. Protect it. Sufficiency means safety. It means contingencies. It means insurance.

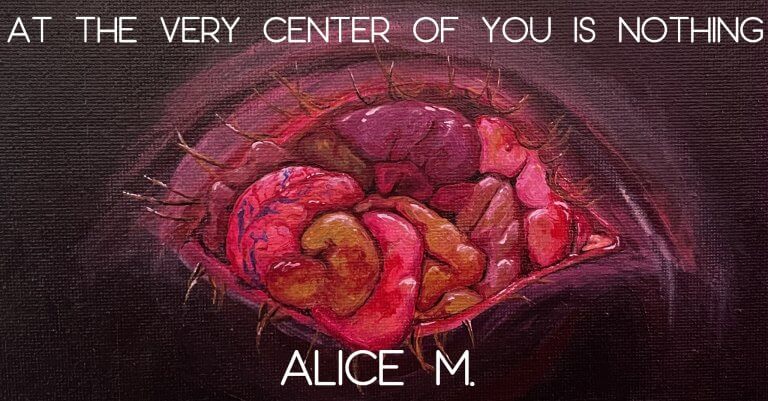

The lord’s light is a fathomless null. Sometimes you’re afforded a glimpse and it’s a tunnel on the other side of which you crawl on the accordioned car’s ceiling.

The masks were thin, pliable. They attached to her skin, seamless. They emoted for her, always appropriate, guaranteed to fetch the reaction she wanted.

The Weatherman describes the snow as dumping. Feathery bundles fall against all things and accumulate against all things, and besides that: the grey, and the cawing of invisible birds.

It was exciting and sad and over too fast and underwhelming and amazing, all at the same. It was all of it. It was beautiful.

Like anything, Hot Wheels has a language. Like any language you encounter, you want to make this one your own.