The purchasing of books is life’s finest pleasure. And while I often have a stack of them unread, they are read eventually, and therefore this habit does not seem excessive or indulgent to me. It is perhaps a bourgeois affectation—there is something embarrassing of an over-large personal library—but there are certainly less healthy ways to spend one’s money. I am no stranger to that, certainly. If God and constancy may will it, that period of my life is closed shut, like a book I’d like to forget entirely. Those pages are wine-soaked anyhow, grainy with drug-powder, the words to those many stories smudged and barely legible. Yet unfortunately, I had upset an important balance: I was buying too many. If I bought, say, four books, I would read three of them immediately, and leave the last for some later time. But now I was acquiring more than ever. While I am a prodigious reader, I couldn’t keep up. Yes, I am one of the top admirers of literature in the world, currently, and anyone in my life (the few, that is) can attest to that. So, as you can see, this position of mine had gotten the better of me. I could count at least 150 books in my possession I had not yet read. Many of these books were purchased during various publisher’s and bookseller’s flash sales, when a $18 paperback can be purchased for a measly six, shipping included. It’s hard to stop oneself in those moments, erratically clicking on as many attractive titles as memory allowed me to recall. And now, well, 150 books! That’s simply too many left unread in one’s possession, and so I promised myself I would buy no more until that pile had shrunk by half. And, in the case I badly wanted to read a book I did not have access to, very badly wanted to do this, then I would either have to wait, or see if it was available at the public library. God, grant me constancy!

I went to the library to acquire Too Loud a Solitude by Bohumil Hrabal. This book had been recommended to me by a well-meaning friend. The recommender, the doorman of my building, said it read to him like something I would dream (I often tell him my dreams, for he is the only friend who tolerates this, always a smile on plump Horacio’s cherubic face). Well, of course I found this comparison flattering, and felt I needed to read it as soon as possible. Sometimes books announce their presence to you, like some vagabond courier knocking haggard upon the castle walls with an important message. Leaving the library with the slim volume (it is a mere 80-page novella, among the best kinds of books there are), I flipped through its pages and was left agog: the prior library patron had annotated it. And not merely lightly annotated—they had underlined, circled, and written words in the margins of almost every page of the book. It is a public book, and they had made it private. My reading, effectively, had doubled: not only would I read Too Loud a Solitude by Bohumil Hrabal, but I’d have to read this phantom reader’s version as well. I considered returning it. I did not want this person’s version of Too Loud a Solitude. I didn’t even know them. What if they had very bad ideas? I feared their version of the novella would merge with the one printed by the publisher, and they would, unknowingly, from the past, destroy the effects of this book on me.

I tried to ignore this phantom reader’s pointing and gesturing as I read. The plot of the book was simple enough: an old man destroys books using a hydraulic press. It is not clear why. He is completely insane and an alcoholic. But why did this phantom reader insist on underlining the fact that this drunk and insane man had worked at this hydraulic press for 35 years? The narrator repeats this fact, it’s true, yet this reader felt it necessary to highlight the number of years every time. I could not feel anything but contempt for this version of Too Loud a Solitude by Bohumil Hrabal. It does not matter that this old man has been at this work of destroying books for 35 years. It could have been 40 years, or 20. The effect would remain the same. The author had merely made an arbitrary decision. 35 years. Yes, authors enjoy doing a bit of this all the time: the marquis went out at seven in the evening and so on. The curtains in my room are blue (they are white).

This phantom reader-cum-writer (for now, they had written their own version of Too Loud a Solitude by Bohumil Hrabal, which we could call Too Loud a Solitude by Bohumil Hrabal 2, or perhaps, My Too Loud a Solitude by Bohumil Hrabal by Anonymous) had many things to say about the book in question. Some of their marginal notes said: “love for destruction” and “destruction” and “against common sense” and “discovery” and “loneliness in society” and “weird tenderness to work tools” and “power of books” and “USSR?” and at the end of the book were a series of furious notes, completely and utterly illegible.

Was this person fucking stupid? Were they just a fucking complete fucking idiot? A total degenerate moron? They had heavily underlined or added multiple stars (drawn as if the person holding the pen were in fact an illiterate child or a mental invalid) to the following words or phrases: “slaughterhouse” (heavily underlined, starred), “too loud a solitude” (heavily starred, if you can believe it), “the heavens are not humane” (underlined multiple times), “too loud a solitude” again (heavily starred, again). When I had finally reached the end of Too Loud a Solitude by Bohumil Hrabal, I felt annihilated. Not by the novel in question, no, but by this phantom reader-cum-writer’s new version of the book. Their stupidity, I found, was so boundless I felt certain then that the human project was completely doomed. Completely, utterly doomed. Nothing would ever get better. Things would only get worse. Every day, I realized, was a testament to this fact: life itself was the experience of being surrounded by entropy, atrophy, and necrosis. But most importantly, it was a testament to boundless stupidity. Nothing should have existed in the first place. And in fact, it was the stupidity of nothingness to have created existence by accident.

I realized, then, there was only one thing left for me to do. I would either have to hang myself (the thought of which turned my stomach), or I would have to kill this person. Anonymous. For they had done something of irreparable harm: they had forever damaged Too Loud a Solitude by Bohumil Hrabal which had led me to lose complete faith in the human project. I could not merely go out and buy myself my own copy and read it again, unsullied by this silly and ridiculous and more importantly, very stupid person. That initial phantom reading will have forever imprinted on me, and therefore, completely and utterly destroyed Too Loud a Solitude by Bohumil Hrabal—a book, incidentally, I did not really like, which is in many ways beside the point. The only punishment I could fathom was to end their life. Because then I could say we will truly have had a tit-for-tat: I will have altered the course of their existence (by ending it) in exchange for their having ruined my experience of Too Loud a Solitude by Bohumil Hrabal, a book I didn’t like, and more importantly for causing me to lose faith in the human project. It’s possible I would have liked this book much more had I not first encountered it in this fallen state, and perhaps then, I could have gone on living in a satisfactory manner. The human project could have seemed salvageable. I could have continued to eat breakfast and so on, I could have continued to make love with beautiful women and so on, but now I had lost complete faith in the human project, and everything, utterly everything, had become equally ruined.

But, of course, I first needed to find out who they were. This proved trickier than I imagined, the more I thought of it: I had assumed, perhaps incorrectly, that it was the previous library patron who had done this. But in fact, it could have been the patron before that one, or the one before that, or the antepenultimate lender. The more I thought of this possibility, the more I felt enraged: they had not only permanently ruined this book for me, but for, perhaps, an entire population of readers. There could, by all rights, be a small city of now permanently damaged readers, who are to walk around for the rest of their lives with this version of Too Loud a Solitude by Bohumil Hrabal residing within their forever diminished personhood. So, in fact, one of the reasons the human project was doomed, utterly and completely doomed, could have been for the fact that—given so many readers had read this version of this version of Too Loud a Solitude by Bohumil Hrabal—they too had given up on the human project, and they too had lost the will to improve the conditions of life in any achievable fashion. And if this were to happen to several people, all from the same source, then that hopelessness would spread like a bacterium. And as we know, when something of that nature goes untreated, it’s over. It’s completely over. In many ways, I thought to myself, it was conceivable that this version of Too Loud a Solitude by Bohumil Hrabal could be the inaugurating gesture of the human apocalypse itself. If I did not do something about it, if I did not stop it right then and there, I would be allowing the annihilation of all that was good and true and meaningful on our planet. I was so overwhelmed by the realization I felt the need to consume my third bowl of chocolate cereal for the day (I would typically admit only two), and this I always did in my study, which I called my suicide den, where I kept all my books, hundreds of them scattered in idiosyncratically designed piles for reasons which I cannot address.

It struck me, then, that the passage of my thinking had led me off toward an unexpected detour: while at first I thought I had lost all faith in the human project—and, indeed, I had—I was now, quite ironically, put in the position to save the possibility of the human being by ensuring that no other person would ever read this book. If some of the damage had already been done, and surely it had, I could at the very least stop it dead in its tracks. And so, of course, while some people, a small band of citizens, surely, will have been permanently damaged (and I forever would be one among their number—their leader?), I had the power to prevent this insipid disease from spreading, and in that way, save the possibility of the human being. And yet: I felt a profound sympathy for my fellow comrades. Who were they? Had they all hanged themselves? Perhaps they were spreading their necrosis—no fault of their own—in our little community, irreparably poisoning all with ears to hear. So now, I realized, my labor had not doubled, but grown exponentially: not only would I have to kill Anonymous, this phantom reader-cum-writer, but I would have to kill all who had read this volume—out of pity, and diligence, of course—so that they could not spread their human necrosis as a result of having read Too Loud a Solitude by Bohumil Hrabal by Anonymous.

This would be much easier than I had at first anticipated. My only other friend in the world, besides Horacio, was Sherman, the steward of our public library. Now, this might strike one as curious. How could such a prodigious purchaser of books be on good terms with a librarian? Surely, one might think that the average librarian would treat me with a bit of suspicion: I was a profligate and erratic purchaser of books. But no, this was not the case. Sherman was my next-door neighbor. I live in 7-H and he lives in 7-G. In fact, it was Sherman who had convinced me to come to the library in the first place: I was carrying inside a bundle of books that had recently been delivered to me, when I complained about the excess of my habit, in passing. Sherman, ever the perfectly polite neighbor, chuckled and said, “You should stop by the library, then,” he said, “not that you’ll need it, it seems.” I admit to having found this last remark a little distasteful. Not that I would need it? One always needs books. More and more books… For there is nothing but books. (People are disposable. The human project is doomed, after all. But books are something else, and of course literature is better than life.) I forgave him for his careless comment, but I have not forgotten it.

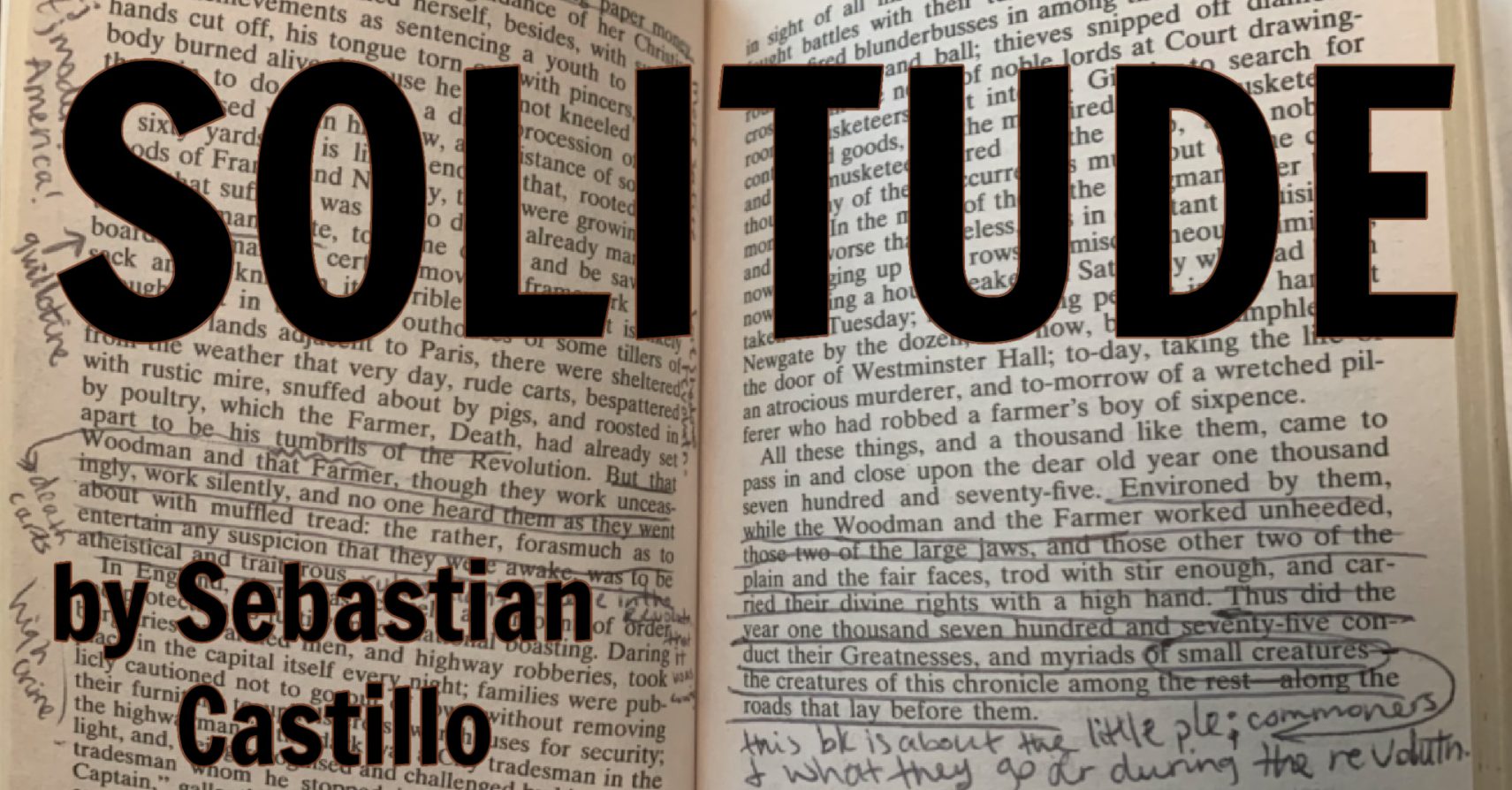

In the morning I knocked on Sherman’s door. He had just finished his breakfast and was preparing to leave for work. I sheepishly submitted to him my request: is there any chance he could tell me how many people had rented out Too Loud a Solitude by Bohumil Hrabal, and, if so, could he give me their names? I crafted an excuse: I wanted to do an art project, I said (an art project!): I would photograph, and interview each prior patron who had rented the book, and I would have an individual discussion with each of them. This way, I said, all of these prior patrons will have unwittingly been in a book club, in the future, without knowing it; and by sharing their unique perspective on the book, the art project would demonstrate the importance and trans-historical value of literature, that great unifier of the human project, I said. Once finished, I would collect these interviews in a book, which I would call Solitude.

“I’m really not supposed to do that sort of thing,” he said. I could see Sherman was chuffed. Bits of flax seed stuck unattractively to his teeth, and I could hear his toddler child sing a dullard song to herself from the living room. She threw her toy at the toy dog. “But that’s such a great idea. I’m sure our director would agree. We’re always trying to find some way to drum up interest in the library. I would have to get his permission. Come by later, and I’ll see what I can do.”

I was thrilled. Little did he know, of course, that he had just quite literally signed several people’s death warrants. For indeed I would seek out each one of these patrons, and need to kill them all. My logic was: if I confronted Anonymous about his scribbles, if I approached this strange idiot man at his house with a copy of this version of Too Loud a Solitude by Bohumil Hrabal and, shaking the slim volume, asked, “Did you do this? Did you mark up this library book?” he would naturally lie. There is no denying he would lie. And so, as a safety precaution, I would have to kill each and every single one of these readers of this version of Too Loud a Solitude by Bohumil Hrabal, to ensure the success of my plan. I would be the last living being poisoned by this text, I would have to suffer that my whole life, but I will have stopped an inchoate bacterium from spreading any further than it needed to, and by doing so, I will have saved the possibility of the person.

I returned to my quarters and took a nap. I no longer had to work, because of my lottery winnings, and subsequently had taken on an irregular schedule: I would wake very early in the morning, read 60 or 80 pages of whatever book was currently on my pile, then take my breakfast and sleep for three or four hours. In the late afternoon I would rise, and either visit the park, read more, or begin my long and slow dinner preparations. Then I would eat, and read even more until I felt my eyes grow heavy in their sockets, and sleep for the evening. But today things would be different: I needed the extra rest to gather my strength for my forthcoming travels and revenge plot.

As I was leaving my building, I was struck by a horrific thought: had Horacio—who first recommended this book to me after all—acquired this book from the library? Would I have to kill my poor friend, dear Horacio, a wonderful and cherubic man, a stalwart of all that was valuable in the human project, etc.? And, indeed, if he had read this library copy, and had somehow survived its assault, perhaps my calculations were in error? Perhaps it was only I who had been so damaged by Too Loud a Solitude by Bohumil Hrabal by Anonymous, and my entire revenge plot upon which I was to embark was an unforgivable calumny against these innocent souls (save for, of course, Anonymous, who deserved death no matter what). I stood in my building lobby and wept. Please, no!

Horacio was sitting on his stool looking at something on his phone. It was surprisingly sunny outside, despite the time of day, though perhaps I had been indoors for too long. I could barely manage a word to him.

“Good afternoon, Mr. Sebastián,” he said to me, bright and cheerful as always.

“Horacio,” I said, “I have a very important question to ask you. It is of too much importance I can scarcely tell you… Too Loud a Solitude by Bohumil Hrabal. How did you read this book?”

“I started on the first page.”

“No, no, Horacio… Where… did you get this copy?”

“Oh. My cousin lent it to me. He’s getting his degree and had to read it for a creative writing class. He said it was too crazy and made him laugh too much.”

“So, you didn’t get it from the library?”

“My cousin lent me his copy. Did you like it?”

I embraced Horacio and kissed him on the lips. He would be saved! The human project! Ah!

“You’re crazy man!” he said, laughing, and pushed me off him.

“Horacio! The human project! Ah! I will make you its king, my good man! I will make you the governor of a little ínsula, just like Sancho Panza! Except actually! Ah!”

“Thank you, Mr. Sebastián,” he said, and returned to the endeavor of his phone.

My walk to the library felt blissful and light. I was doing something important, finally. I had been reading all this while as preparation, I now realized. Literature was the preparation, and I was preparing myself for something. And finally: here it was. The future of the human project, in my hands. I would have to do something awful, something unbelievably violent, depraved, and disgusting, but it would be for something far, far greater than I could have imagined. The possibility of the human.

The library was mostly empty. Though I had been inside it but a few days prior, I had somehow forgotten its incredibly high ceilings, its battered bookshelves and threadbare reading chairs, its trademark musty smell—almost like tobacco, though no patron or worker had smoked a cigarette inside its walls for many decades now. Sherman was by the computers, helping an elderly woman with the device. She was pointing at the screen, and yelling at him. Yet his face was the picture of warmth and composure. Sherman, the human project! Ah! I tarried by the front desk.

“Sebastián!” Sherman said, once he was finished, approaching me. “I’m glad you could make it. Unfortunately, I have some bad news.”

I feared this possibility. The director was onto me, then. He saw through my ruse. He must have taken a glance at Too Loud a Solitude by Bohumil Hrabal, and probably felt sick to his stomach, seeing how marked up it had been, and then realized what an effect something like that could have on a future reader—indeed potentially driving that reader to an unforeseen madness that would transform into bloodlust. He knew what I was after. He had now become my new enemy. The director. I would have to devise a different plan of attack.

“I didn’t even have to speak to the director,” Sherman continued. “When I checked the records, it looked like the book had only ever been rented out a single time before you, by one of our long-time regulars, Harold Pinter. Funny about the name. No relation to the writer, of course. Anyway, yeah, Harold sadly passed away last year. He was quite old.”

“Passed away?”

“Well, he stopped coming in, which we all thought was strange—he was practically here every day—and then Shannon found out he had died in his house. One of his neighbors found him. His wife had died a few years back and he became a real regular, as I was saying. He was pretty lonely. He had a terrible habit of marking up all the books he took out from us. I politely admonished him but he just smiled. I didn’t have the heart to do anything about it. He just wanted to be around people. Poor guy. Don’t know if he had children. Anyway, I double checked and it looks like you were the first person to check out this book since him.”

“Are you certain?” I asked. “Sherman, are you absolutely certain no other person has read this copy of Too Loud a Solitude by Bohumil Hrabal?” I was once again nearing tears. The human project. The possibility of the person.

“Yeah, it’s a shame,” he said. “No one reads anymore.”