Ten years, Dad broke his back for the railroad for ten years and they laid him off, leaving him unemployed with a new mortgage and us two boys to raise on his own. My little brother Jeremy and I became the poorest kids of our middle-class neighborhood. The unnurtured ones, the unsupervised ones, the ones who strayed the streets in the middle of the night. Feral beasts snapping at the moon. The ones sent into the store with a book of food stamps while our father waited in the car. And when we objected, because we had pride too, our father would say, “It doesn’t matter to me. You guys are the ones who want to eat. If you don’t want to eat, then fine, don’t use them.” We did want to eat. We were always hungry.

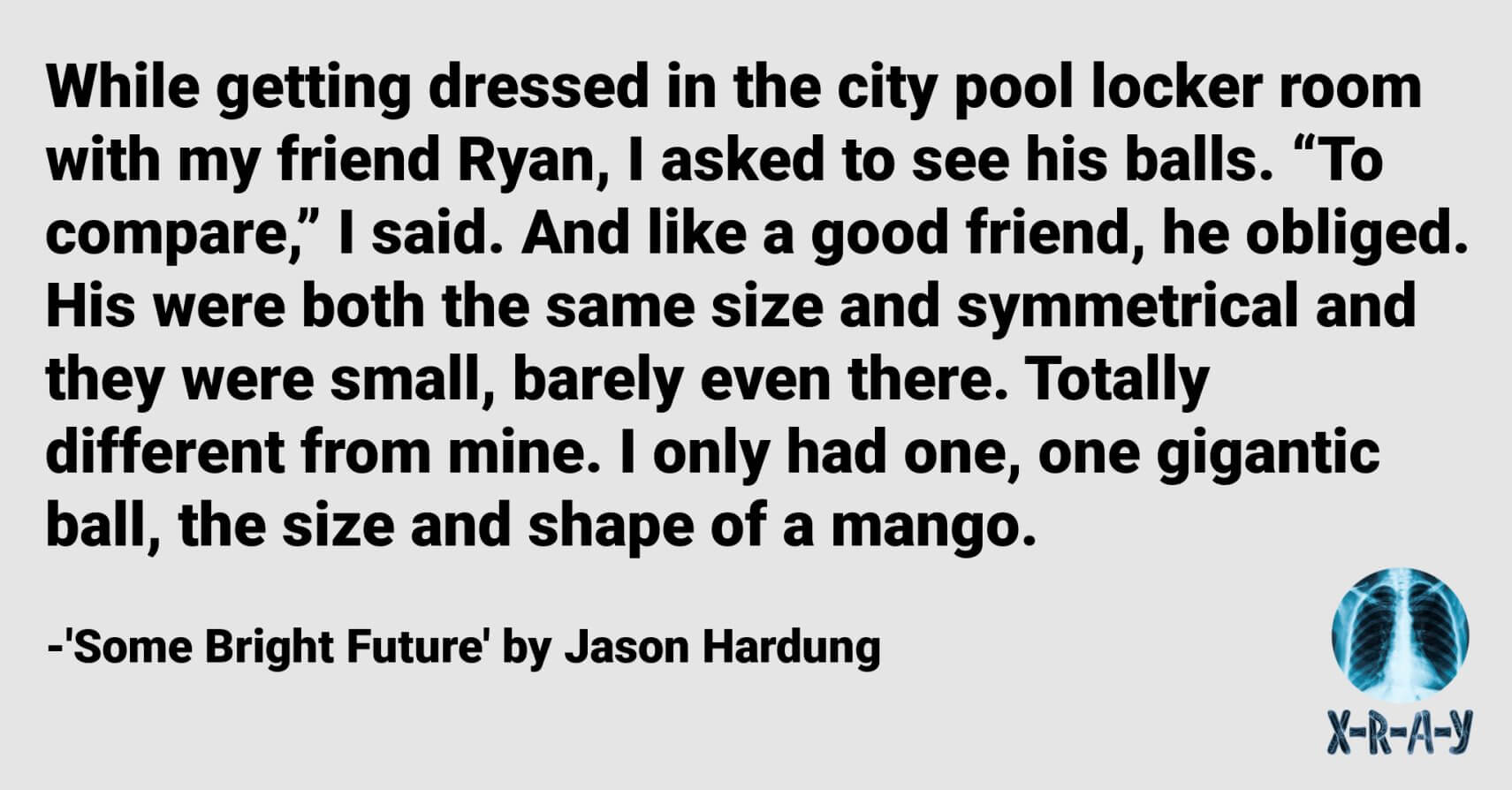

This was around the same time I realized something was wrong with my balls. Not every morning, but most, I’d wake up with a dull pain in my gut. Not enough to be debilitating, just enough to be uncomfortable. And sometimes when I walked, I could hear a suction noise coming from down there. That was the worst part. A faint pulling a shoe from the mud-type-sound that I hoped nobody else could hear. At the time I was navigating through the beginning stages of puberty when everything is a bit strange anyway and I hoped this problem was just another symptom of becoming a man, like getting hair in places I never had hair before. But one afternoon I found the courage to bring it up. While getting dressed in the city pool locker room with my friend Ryan, I asked to see his balls. “To compare,” I said. And like a good friend, he obliged. His were both the same size and symmetrical and they were small, barely even there. Totally different from mine. I only had one, one gigantic ball, the size and shape of a mango.

Even if I wanted to get it checked, Dad couldn’t afford the doctor, not without the insurance he lost with his job. Medical care was no different than a new pair of Jordans to my brother and me, just another luxury we couldn’t afford. Dad was constantly stressing about all the things we couldn’t afford. It was his version of preventative care. Staving us off with guilt prevented us from asking for things. Besides, what child wants to go to the doctor?

My parents, like most, charged hard into the Win-One-for-the-Gipper-Day-Glo-Nuclear-American-Grudge-Fuck of the 1980s. They bought our first home the summer before I began grade school. No more trailers or cramped apartments for us. We were moving on up! As I’m thinking and writing about those early days on Everglade, it’s the smells that return more than anything. Milkweed, sunflowers and sage, the rain, creosote from the railroad tracks, smoke from mom’s Marlboro Lights. Pioneers smelled many of the same things, I imagined. The Oregon Trail crossed less than 100 miles from there. Perhaps the pioneers thought of it as the smell of some bright future, the way we did. We lived on the last street of the sub-division. Beyond our backyard was all prairie. Standing on the back deck, you could see the Great Plains unfold clear into Nebraska.

That first summer in our home I saw a tornado back there. The sky turned from blue to black. The rain came down in sheets, then the hail. Just as quickly the rain and hail stopped and it became deathly quiet. A funnel poked out from the clouds. Just a little tail at first, but it kept stretching and reaching until it touched the horizon and it would suck the earth up into it and get bigger and louder until it sounded like a freight train was going to come barreling out of all that dust. Mom’s eyes widened with panic. So wide and blue. I noticed a vulnerability in her I had never seen before, like maybe she didn’t know what to do. This frightened me as much as the tornado. Parents always knew what to do. Dad was out of town cleaning up a derailment somewhere out west. Mom was our only protector. She hurried Jeremy and me under the stairs. She asked what two things we wanted to save in case everything blew away. I wanted my plastic cowboys and Indians. She ran upstairs and got them, along with her Marlboro Lights, a radio and stuffed animals for my brother. We stayed under there until the DJ on the radio said it was safe to come out. Some homes were left with their tops peeled back and some weren’t left at all. People stood in the wet street sobbing. One screamed, “Dear God please!” I wanted to tell him it was God’s fault in the first place. How did he not know this? I was just a dumb kid and I knew.

It was only a couple of months later when I caught Dad bawling on the back deck. The first time I’d ever seen him cry. He wouldn’t tell me what was wrong but deep in the tissue of my heart I felt a sadness, a loss—like things would never be the same. Seeing my dad cry knocked my world off axis. I witnessed a secret world, the adult world, a world I wasn’t meant to see. One where your parents aren’t bulletproof. By that winter, they had split-up, living in different places. Dad took custody of my brother and me. We stayed in the house while Mom moved across town to a small basement apartment.

Seventh grade would be starting soon. I’d be in a new school, with new kids and a chance to mold my own reputation. To do that, I needed a pair of parachute pants. My mind was set on them. I had many fantasies of the nylon swish swishing as I walked down the halls of Johnson Junior High. The other students whispering to each other, Is that kid from the big city? I bet he’s a professional break dancer. I begged Dad for weeks for these pants. “For back-to-school clothes,” I said. And I think he saw how important they were to me, because he took me to look for them. We found one pair in all of Cheyenne that were cheap enough for him and small enough to fit my puny waist. Of course, they weren’t the real Bugle Boys, just knock-offs. I didn’t care. Anything not hand-me-down, was designer to me. When I got them home, I found a small rip in the crotch. I was disappointed but I kept my mouth shut. If I told Dad, he’d force me to take them back. Like I said, they were the only pair, anywhere.

One day I was just messing around and I pulled my big ball through the rip—a furless rodent squeezing through a quarter-sized hole. A big furless rodent with protruding veins all over it. That’s what it looked like. We’d be walking down the street, or down the aisles of the grocery store and I’d have that one ball hanging out of my parachute pants just waiting for my friends to notice. When they did, I’d pretend I didn’t know it was hanging out, they’d laugh, then I’d laugh even harder and we’d feel better than before, because laughing releases feel-good chemicals in the brain. And I was really hoping one of them would say, “Hey mine looks like yours.” Then I wouldn’t feel so alone. And I guess it worked because one night, my brother confided in me that his balls looked like mine. He showed me, and it was true. They were like mine, only smaller. Which made sense, since he was two years younger. He made me promise I wouldn’t tell anybody and I promised. I felt some relief knowing I wasn’t all alone. It wasn’t one of those “one in a million” deformities.

To register for seventh grade, students were required to get a physical. Dad had no choice but to fork out the cash. I’d heard the horror stories from older kids. Tales passed down from generation to generation. A creepy doctor forcing them to pull down their pants and cupping their balls in his long arthritic fingers. “Cough,” the doctor would say. And he’d say it with a cigarette hanging from his lips and the cigarette’s long ash would be about to fall on the floor. And what if when he told me to cough, I got hard? Could penises tell the difference between the hands of a doctor and the hands of a lover? In those days, before the internet, a black and white photo of a woman wearing a bra in a JC Penney catalog would get me hard. But if I got hard when a man touched me, that would mean I was gay. In Wyoming, in the 1980s, gay was not normal, but doctors who smoked were. I don’t believe much has changed.

The Urgent Care next door to Kum and Go was running a back-to-school deal on physicals, only $19.99. I cut the coupon out of the paper and Dad drove me over one rainy afternoon in August. He handed me a twenty-dollar bill. “What about tax?” I asked.

“Doctors don’t charge tax,” he said. “And tell them to hurry. I don’t want to be sitting out here all night,” he said.

“I’m not going to tell the doctor to hurry,” I said as I got out. Dad sat in the truck and listened to 850 KOA Sports Talk Radio, Home of Your Denver Broncos.

My heart was pounding, thinking of every terrible outcome. What if it’s a cancerous tumor? Or a stillborn twin that somehow got trapped in my scrotum? A nurse checked my vitals. She said, “Don’t be nervous honey.”

A doctor appeared, almost as ancient as the one I imagined. My balls gurgled. I wondered if he could hear it. He tapped my knees with a small rubber hammer. Held my tongue down with a stick. Put a cold stethoscope on my back. Dumb doctor shit. Then came the words I feared, “Drop your drawers young man.”

My face got hot and my hands went numb. It took me a minute while I fumbled with the zipper of my parachute pants. I didn’t have any clean underwear, so I didn’t wear any. As soon as I pulled them down and the doctor saw, he said “Something isn’t right.”

I played ignorant. Real sheepish and dumb. I said, “What do you mean?”

He palmed my testicle and instructed me to cough. I coughed like this: Ach, ach. He shook his head, pushed the ball up into my stomach and held it there. “Does this hurt?” he asked.

The pain knocked the breath right out my lungs. “Yes,” I squeaked.

He told me to lay back on the bed. Paper crinkled under my bare ass. He squeezed my ball between his thumb and finger and asked if that hurt. Frantically, I nodded. I wanted to hit the son of a bitch.

“Young man, speak up.”

“Yes, it fucking hurts. You’re pinching my balls,” I said.

He told me to watch my language and called for the nurse and the nurse came and he told her, “Put your hand right here.” She held my ball in place while the doctor poked at my stomach. Don’t get a boner, don’t get a boner, I kept telling myself. She wasn’t as pretty as the girls in the JC Penney catalog, but her hands were soft, she smelled good and she was the first woman to ever touch my bathing suit area. Then I told myself not to fall in love. It just wouldn’t work. We were at different points in our lives. When she bent over, a small silver pendant, a cat, dangled in her cleavage. It seemed so warm and comfortable in there. I wanted to burrow down in there, curl up and take a nap. I had to stop looking before I did get turned on. So I thought of my step-grandaddy instead—his yellow teeth, the hair jutting from his nose and ears and the way his boobs sagged when he’d walk around the house with his shirt unbuttoned.

The doctor shook his head, sighing as the examination went on. He seemed annoyed that I had a real medical problem, that I was making him work for his $19.99. He asked where my mother was.

I said I didn’t know. I hadn’t seen her in a month or so.

He asked how I got there.

I told him about Dad in the parking lot listening to 850 KOA Sports Talk Radio. He had the receptionist fetch him. When Dad came in I was still on the table with my pants down, the nurse resting her hand on my thigh.

“This young man has an inguinal hernia. Most likely it’s congenital. When his testicles dropped, the hole in the tissue never closed back up, allowing his intestines to fall through the muscle into his scrotum. It looks like he only has one testicle, but there are two in there. Bottom line, he’s going to need surgery,” the doctor explained.

“How much does that cost?” Dad asked.

“I have no idea,” the doctor said. “I’m not a surgeon.”

“Are you sure he needs surgery though? Could he just grow out of it?”

“Into it,” I said. “My ball is big. I’d have to grow into it.”

The doctor paused, his eyes straining over the rim of his glasses. “Mr. Hardung, if his intestines tangle and rupture, it would poison his whole body with waste. He could die. He’s lucky it hasn’t happened already. I can’t give him the go ahead to participate in any physical activities until this thing is fixed.”

The pain on Dad’s face, I was feeling that way on the inside, and not just from the hernia. He was stressing over money. On the way home I was going to hear about how we didn’t have any. I was angry at my body for putting this burden on us, for making me uglier than I already was. Puberty was hard enough without the Elephant Man dangling between my legs. I was also really scared. I didn’t want to go at this alone.

“Jeremy has one too,” I blurted.

“That’s not funny,” Dad said.

“I saw it,” I said.

The doctor told the nurse she wasn’t needed anymore, and she walked out of my life. I kept looking towards the door waiting for her to turn around and say, “Wait, we can make it work,” but she never did.

Dad took his glasses off and rubbed the bridge of his nose.

“Can I pull my pants up now?” I asked.

The doctor said, “Why are they still down?” Then he warned me not to participate in any “rough housing,” until six weeks after the surgery and I said I wouldn’t.

As soon as we got home Dad confronted Jeremy. “Pull down your pants.”

“Why? I didn’t do anything. Are you going to spank me?” Jeremy asked.

“I just need to see something.”

“See what?”

“Are your balls fucked-up like his?”

Jeremy glared at me. “You promised. You baby.”

“I’m saving your life. That’s what I’m doing,” I said.

“If you don’t show me, I will spank you. This is important. Pull down your pants.”

Jeremy argued, but he pulled them down.

Dad looked. “They seem fine to me,” he said.

“Get closer. Look, they’re just like mine,” I said.

He bent down for another look. Once he saw that I was right he threw up his hands. “Well, I’m fucked. Why didn’t you guys ever say anything when I still had insurance?”

“Four years ago? I was eight and he was five. How were we supposed to know?” I asked.

“Well, how am I going to pay for two surgeries?”

Jeremy said, “I’m not having surgery. You don’t need to pay for me.”

And I said, “Then your guts are going to get tangled and leak shit into your whole body. Your shit is poisonous. You realize this, don’t you? You’ll die. Is that what you want?”

“I guess I’ll die then.”

Him and Dad went on arguing while I snuck off to go play tackle football with the super religious kid next door who had one shoe with a tall sole and one shoe with a normal sole, on account one leg was shorter than the other.

Then the time came to check into the hospital. I’d be missing the first week of junior high. In some ways it was great, because I was scared to start a new, way bigger school and wanted to put it off as long as possible. On the other hand, by the time I started, the cliques would be formed, everybody would know where their classes were, where they sat at lunch, who their teachers were. I’d be so far behind. After all the nerds had already been tormented for a week, here I’d come, a brand-new nerd. I’d be the nerd the other nerds picked-on to make themselves feel less insecure.

Jeremy and I shared the same hospital room. They wheeled me off to the operating room first. The anesthesiologist counted down from ten. Six was the last number I remembered. When I came to, I was naked and thirsty in a brilliant, white room. My skin was stained yellow from my belly button to my knees. Iodine, as I later learned. The two pubic hairs I had been growing out were shaved off and a row of ugly stitches ran across my groin. A person in blue scrubs and a mask hovered upside down, above my face. She said, “You’re done,” and stuck a sponge on a stick in my mouth. Three hours had gone by and I couldn’t recall one second of it. As I became more coherent, the more my body hurt.

They wheeled Jeremy into surgery as they were wheeling me out.

When we were both done and back in our room, an old lady brought us pillows with tiny storks on them. Her old lady group made them for sick babies to make sick babies feel better. But I think it made the old ladies feel better, like they still had something to contribute to the world. Selfish old ladies always thinking of their needs first. Jeremy was already up, waltzing around the room, fucking around and laughing. Me though, I couldn’t get out of the bed, felt like I took a shotgun blast to the groin.

Both Mom and Dad were there, on opposite sides of the room, the first time they were in the same place since they divorced six years earlier. The surgeon popped in to explain his procedure. He wasn’t sure who to address, looking back and forth between the two. The resentment they held for one another was pent-up in their faces. And it hit me, the four of us probably would never be in the same room again unless me or Jeremy got married or died and I thought back to the tornado bearing down on us and Mom running upstairs to get our favorite things and how I never questioned if she’d make it back. I knew it would take more than a natural disaster to keep her away then, but I wasn’t so sure anymore. Seeing them still hating each other like that and all the times I heard them talk bad about each other made it apparent that love wasn’t guaranteed to last forever. Love is a pair of parachute pants. Holes form, we grow out of it. And I couldn’t help but wonder, would they stop loving me one day?

A nurse came in, lifted my gown and checked on my balls, in front of my parents, my aunt, uncle, cousins. I think my grandma may have been there. They all got to see. Then the nurse asked about the pain, on a scale of one to ten.

“Ten,” I said without hesitation.

The nurse stepped out for a bit, she came back with a bag of liquid and hooked it to my IV. Morphine Sulfate, I heard her mention to my parents. It went, drip, drip, drip. My blood went from cold to warm. How spilled ink consumes not just the surface of the paper but the fibers inside it. I could feel it enter each cell from one side and push the pain out the other. The fear and worry I usually carried was gone. For the first time since I could remember, I didn’t give a shit. About my clothes, my balls, about who loved me and who didn’t. I was numb. I was a cloud. I wanted to feel this way forever.