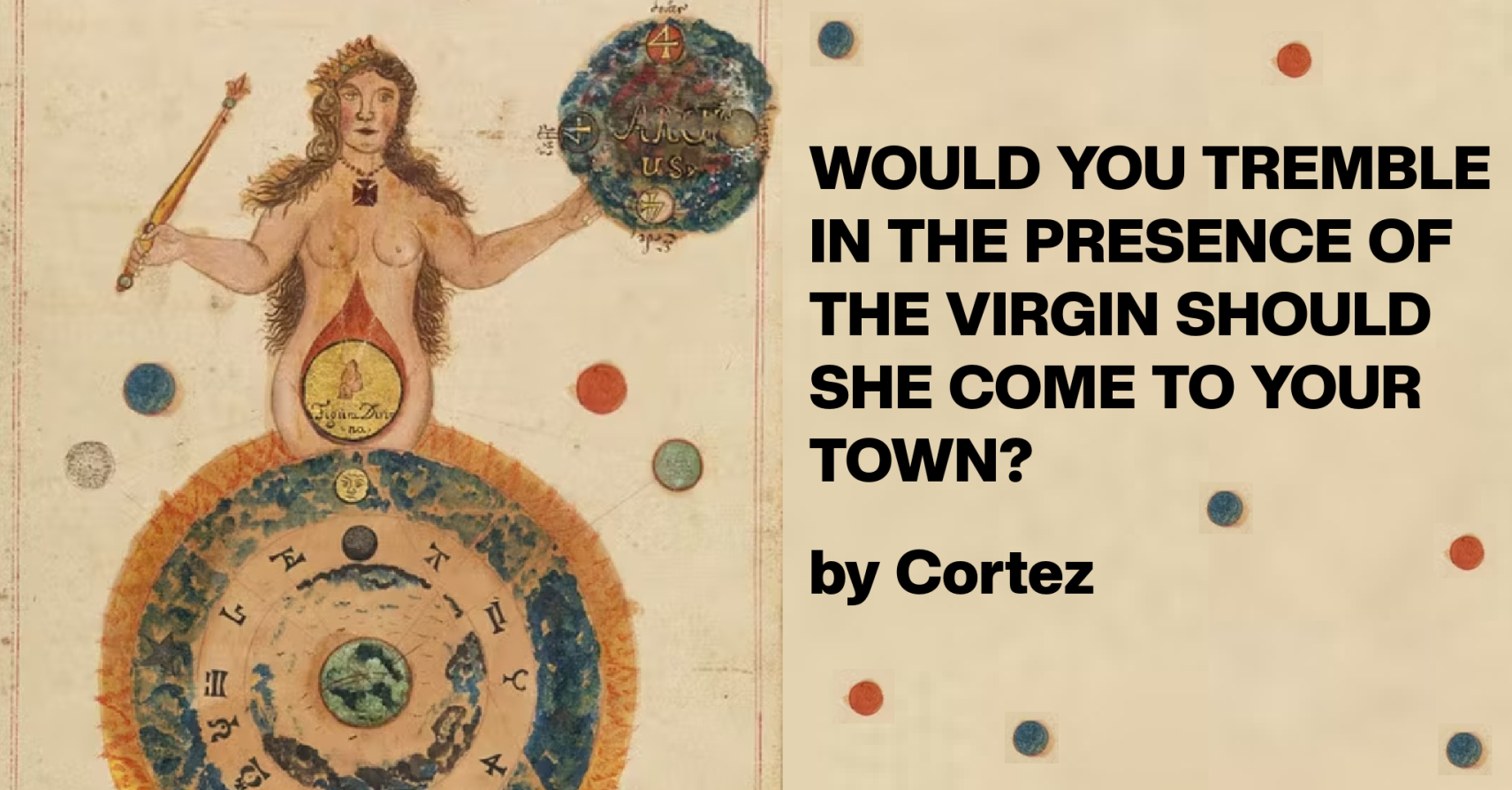

WOULD YOU TREMBLE IN THE PRESENCE OF THE VIRGIN SHOULD SHE COME TO YOUR TOWN? by Cortez

When Mother’s belly bloomed again, she pointed a french-tipped finger at the richest man in town. The accusation, though baseless, haunted him– it polluted his polished lawn, noosed his silk ties. This was a man shrunken, a spirit corrupted, a man of real stature driven sick. But the town was small, and Mother was only getting bigger, and so he wished her away with a lump sum. Mother had two girls at home. The little one, blue-eyed and painted with the peachy, airbrushed skin of Jesus, thought she might’ve been born of dirt, like Adam, or rib, like Eve. The…