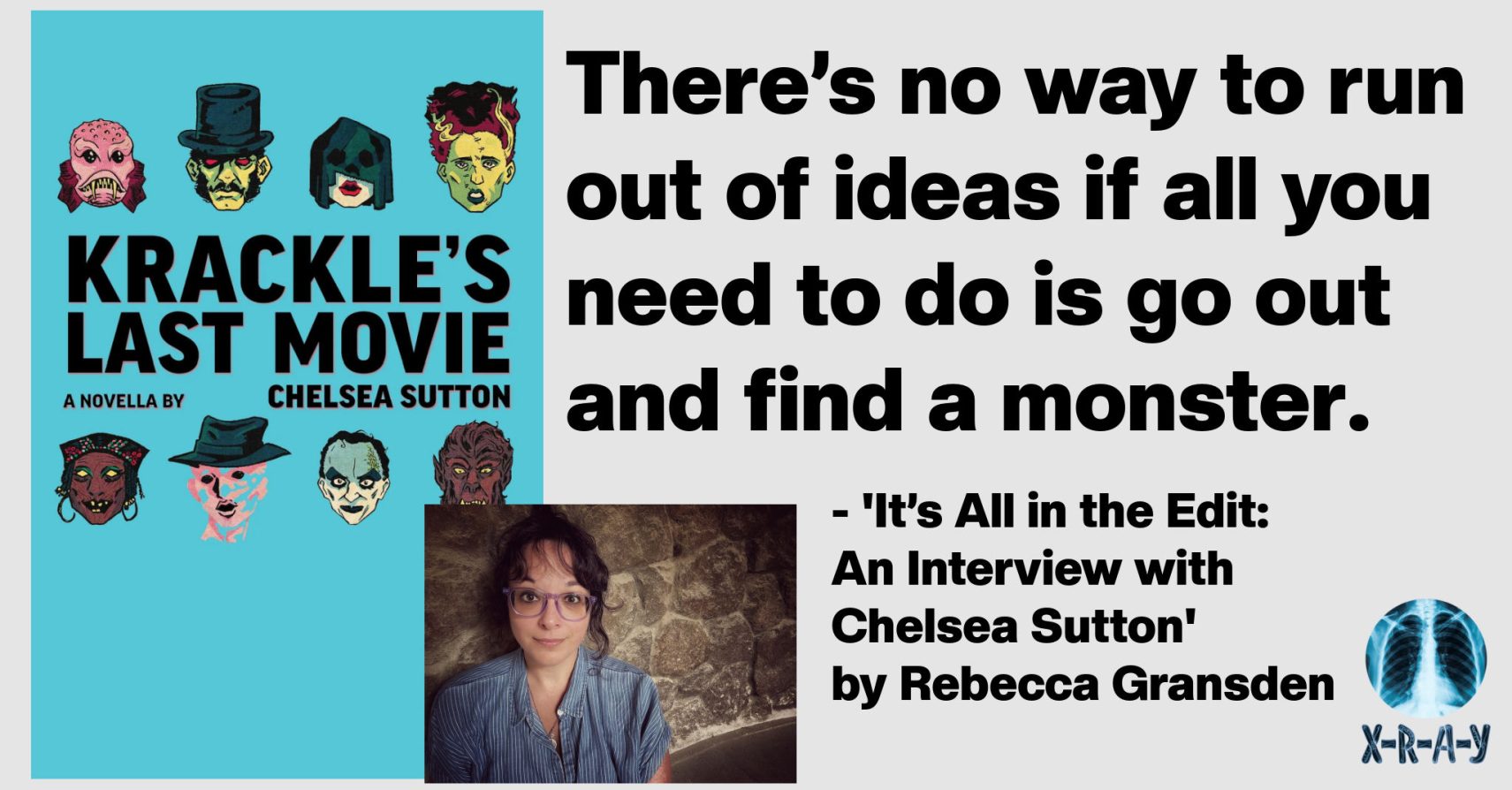

IT’S ALL IN THE EDIT: AN INTERVIEW WITH CHELSEA SUTTON by Rebecca Gransden

Chelsea Sutton’s rollicking novella Krackle’s Last Movie (Split/Lip Press, 2026) deals in magic and monsters. The mythology of horror icons meets the world of the film documentarian, in a whimsical ride full of frisky humour and spooky glamour. At its ghoulish heart the tale is a quest—a resolution residing somewhere within old videotapes and archived audio cassettes. I spoke to Chelsea about the book. Rebecca Gransden: Travelling back in time, what is the first monster you remember? When did monsters enter your life? Chelsea Sutton: Monsters very clearly entered during The X-Files era of my life — which was…