With The Surrender of Man (Inside the Castle, 2025), Naomi Falk examines twenty works of art, using each as both touchstone and springboard for scrutiny of modernity. An exhibition of the psychic space inhabited by the intersection of time, memory and art itself, the book unravels as a stream of commingling impulses. Falk’s often febrile interrogations display a hunger to get to grips with the interior world as it probes contemporary existence. At times raw, inspirited, raging, and contemplative, the volume acts as a catalyst for the author’s questioning nature, and stridently asks what the hell is art for anyway? I spoke to Naomi about the book.

Rebecca Gransden: What led you to The Surrender of Man for the title?

Naomi Falk: The title had been in place before the book was anywhere near being finished. My attraction to it is a little complicated. There’s an obvious element of gendered language that goes hand-in-hand with the biblical proportions of the phrase, and it felt interesting to me to have a title of the book that was pretty deeply conflicted with the text itself. The sentence within which the title is housed is a significant turning point in the text, at least for me.

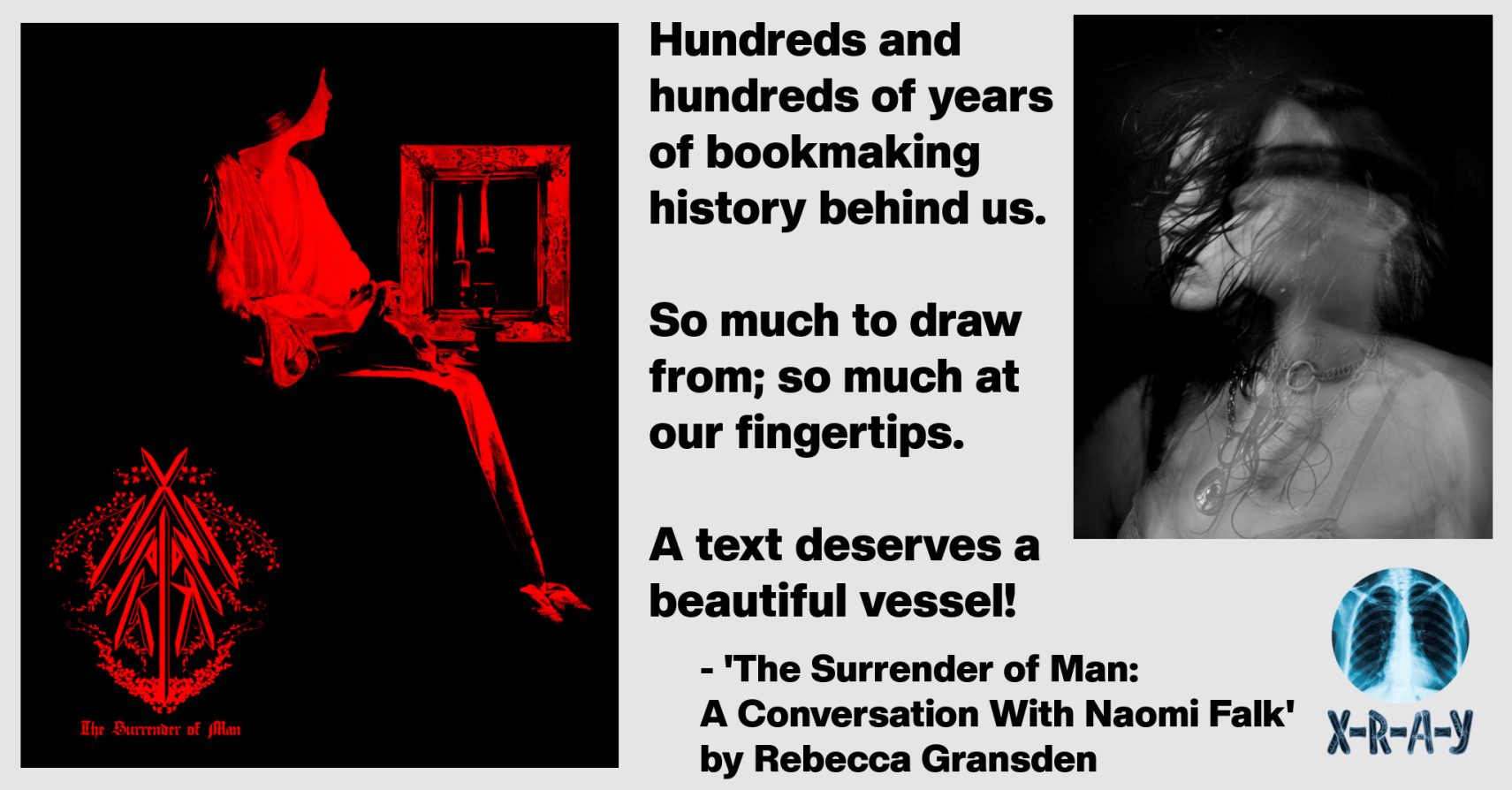

RG: When reading the book it’s immediately clear that a great deal of care has gone into visual presentation. Was this a collaborative process with the publisher, known for their attention to the aesthetic experience of a book, or did you make strong stylistic choices from the book’s early inception?

NF: John Trefry designed the cover and then Mike Corrao designed the interiors, and I am woefully indebted to them both for giving such a gorgeous body to the text. John and I already had such a strong overlapping aesthetic impulse, which was part of the reason I was so intent on working with him. He designed the emblem of my name at the bottom left of the book, which speaks to our mutual love for metal…. We actually did an hour-long set for Montez Radio together a few months back.

RG: Objects possess transformative potential when you look closely, fastened by their makers—both human and otherwise—and cracked into the world.

When considering the book’s formation, how much thought was given to its status as an object, an artwork, in its own right?

NF: I am extremely invested in the book as object; I’ve worked in art book publishing for years; I’m an editor but also a designer and producer and publisher. Of course I’m going to care about those things; this isn’t an assembly line. Hundreds and hundreds of years of bookmaking history behind us. So much to draw from; so much at our fingertips. A text deserves a beautiful vessel! And a book doesn’t have to be expensive to make. I’m not going to waste my time making something that looks and feels like shit, even if I’m fine with buying things that look and feel like shit.

RG: You’ll see how arbitrarily I’ve come across most of these works of art.

An obvious question concerns how each work of art is chosen for inclusion in the book. You cover this aspect at length and I was struck by how the contemplation you offer becomes part of the book’s quality as a whole. When you reflect on the selection process, what stands out to you now?

NF: A lot of the younger artists in the book are folks I met through the passages of my daily life (which is outlined in the text). The lasting creative ramifications that someone’s work can have on you become most pronounced once you’re no longer in continuous contact with the artist: people move, new lifestyles emerge, we grow away from each other and become variants of ourselves that might not be compatible with the people we once knew. But the essence of their art and their ideas linger and entwine with your own work. Those hazy tethers come up again and again. Friendly spirits.

It was also important to me that this not be a book of my favorite artworks. We have lived through such an intensity of listicles and “favorite things” in the past fifteen years, I worry we confuse the artist with the artwork they love…

RG: They are taking over.

The above quote is referring to words, words taking over, and suggests a multitude of interpretations. The book’s language at once contains the potential for manifestation, a means to precision, but also intrusion and alienation, an occupying force. For The Surrender of Man, was a clear stylistic approach embarked upon from the start, or did this evolve over time?

NF: My writing evolved a lot over the course of writing the book, which took quite a lot of time because of the research that went into it (and because of the necessity for me to continue experiencing art to finish it). I kept feeling a pull to abstract the writing more and more, to imbue it with less uninterrupted academicish-leaning research and more language. The art in the book IS the lifeblood of the text, so the feeling of the language really needed to reflect a relationship between me and the art, and not just my projections… It actually caused some problems for me on an artistic level, and I made several revisions to the entire manuscript, which probably made the book messier than it ought to be…

RG: How does the idea of confession arise in the book? Do you view The Surrender of Man as belonging to the tradition of the confessional?

NF: To the extent that I implicate myself in the book, yes I would say it could be shelved within a tradition of confessional writing. I certainly don’t have plans to do it again!

RG: What parts do dreams play in the book? You recount a recurring dream, and many times your responses to art are infused with the rich, uncanny symbolism associated with dreams. How conscious were you of the unconscious when writing The Surrender of Man?

NF: I was possibly even over-concerned with the unconscious when writing the book. My dreams, and the dreams of others, are the wellspring of my writing practice. Increasingly, increasingly, it feels as if life is just the dream’s interlude.

RG: No other generation of writer had been inundated with disembodied—but verifiably real—other people and their thoughts and feelings during the writing process in this way. Felt special, cursed, fresh.

I think it safe to say that we are at a point in history where a lone mind has never before been exposed to such a number of psyches outside of its own. When it came to the writing of the book, is this something you moderated, or, alternatively, encouraged?

NF: To use a phrase received from said outside psyches, there is a fair amount of “whataboutism” that I experience as I write. A tendency to want to make things more and more universal or interpretable to the point where what I am writing becomes only thinly tethered to its original meaning. It’s a real problem, and I’m working on it.

RG: The idea of transformation recurs throughout the book, approached from differing angles. When you set out on The Surrender of Man, did you know what you wanted from it? Has that perspective shifted since its completion and publication?

NF: On a broad level, the yearning and satiation of creating and publishing your work is so bright and abstract; it’s really hard to put into words. At one point in past years it all felt quite far away…I am happy I had the chance to experiment with the format, and that everyone involved with bringing the book into the world was supportive of that. As I mentioned earlier, the opportunity for the text itself to go through a series of new iterations, because of the freedoms I was afforded by Inside the Castle, supported every other intention of the work.

RG: The format of the book seems a natural one for you, and is potentially endlessly mineable. Would you consider a further book of a similar kind, or do you feel you’ve explored the format for as far as it can go?

NF: I aim to keep working within the nonlinear, and mostly nonnarrative. Although my current project DOES have a “story,” the “story” could be condensed into a few sentences. So many other people are writing good “stories.” I’m not a good storyteller, so I can leave it to other people to bedazzle readers with twists and turns and enticing character development, for now.

RG: What don’t you want the book to be?

NF: A definitive guide to interpreting art.

RG: You mention an early attraction to transgression and horror, particularly horror movies. Are there films you would consider as complimentary to The Surrender of Man? Any recommendations?

NF: I’m not sure if any films—excluding, perhaps, film essays—are complimentary to the work, or at least I haven’t found them yet. This text is very much in the service of other mediums. But if we’re talking about spooky movies…I suppose that my impulse for theatrics and drama comes from the obvious blueprints: The Hands of Orlac, any number of Poe adaptations, the Universal Monsters. I am obsessed with giallo films, the Saw franchise, Herschell Gordon Lewis, anything with a fantastical edge, the original and remake of Candyman, Hard to Be a God, Woman in the Dunes, and everything that Anna Biller has ever done. Is this turning into a listicle?

Importantly, my friends Chris Molnar and Amy Griffis and I just saw the New York premier of the new Quay Brothers movie, Sanatorium Under the Sign of the Hourglass. That one is on my required viewing list. No one does it like they do.

RG: Are there notable works you almost included but left out of the book? Or works you’ve encountered since the writing of The Surrender of Man that you wish could have featured?

NF: I mean, kind of yes, but I need to fight that impulse. The purpose of the book seems to be the happenstance nature of so many of the inclusions, and if I tried to think of the scope of art outside of the specific years during which it was written, I would be doing a disservice to my own project.

RG: The messiness of my mind has only become more pronounced as years and their memories accumulate. My ability to thread a cohesive narrative or to focus on a singular topic can’t parallel so many other writers I admire and I’m sure you can tell by the writing here that I don’t really want to find harmony and cohesion anyway.

To what degree is The Surrender of Man a response to internet culture?

NF: I think that most of my work is steeped in my lifelong participation in internet culture. I love the Web; I still feel excited about it every day. It raised me, in many ways. Video games have been instrumental in my writing style. The sense of awe I felt watching my dad play Myst when I was a girl has never left me. The strange collapse of distance between me and friends and strangers in the early years of AIM. Roleplaying in the Neopets forums. Being on MySpace trains… I don’t think The Surrender of Man is a response to the internet insofar as it has a sense of fragmentation or perhaps a lack of “focus.” I am looking for connection (within myself and with others) through my work in the same way that my internet personalities are signals or offerings…

RG: The book is released by Inside the Castle. What attracted you to work with them, and how have you found that process?

NF: Chris had brought Inside the Castle to my attention years ago. I couldn’t believe I wasn’t already familiar with them at the time, because as mentioned previously, I have an existing foundation for appreciating the kinds of texts ITC publishes. Work that offers an unusual amount of experimentation, work that might even be unconcerned with being understood. It’s been the best experience; no notes; a true dream.

RG: I’m screaming into the bathtub because it brings me clarity.

What has The Surrender of Man brought to you?

NF: Solace, quiet, a sense of heightened wonder in regards to others and the work they create.

RG: Where next?

NF: The closure of this portal opens a new one, so now I’m working on a book-length piece of fiction.