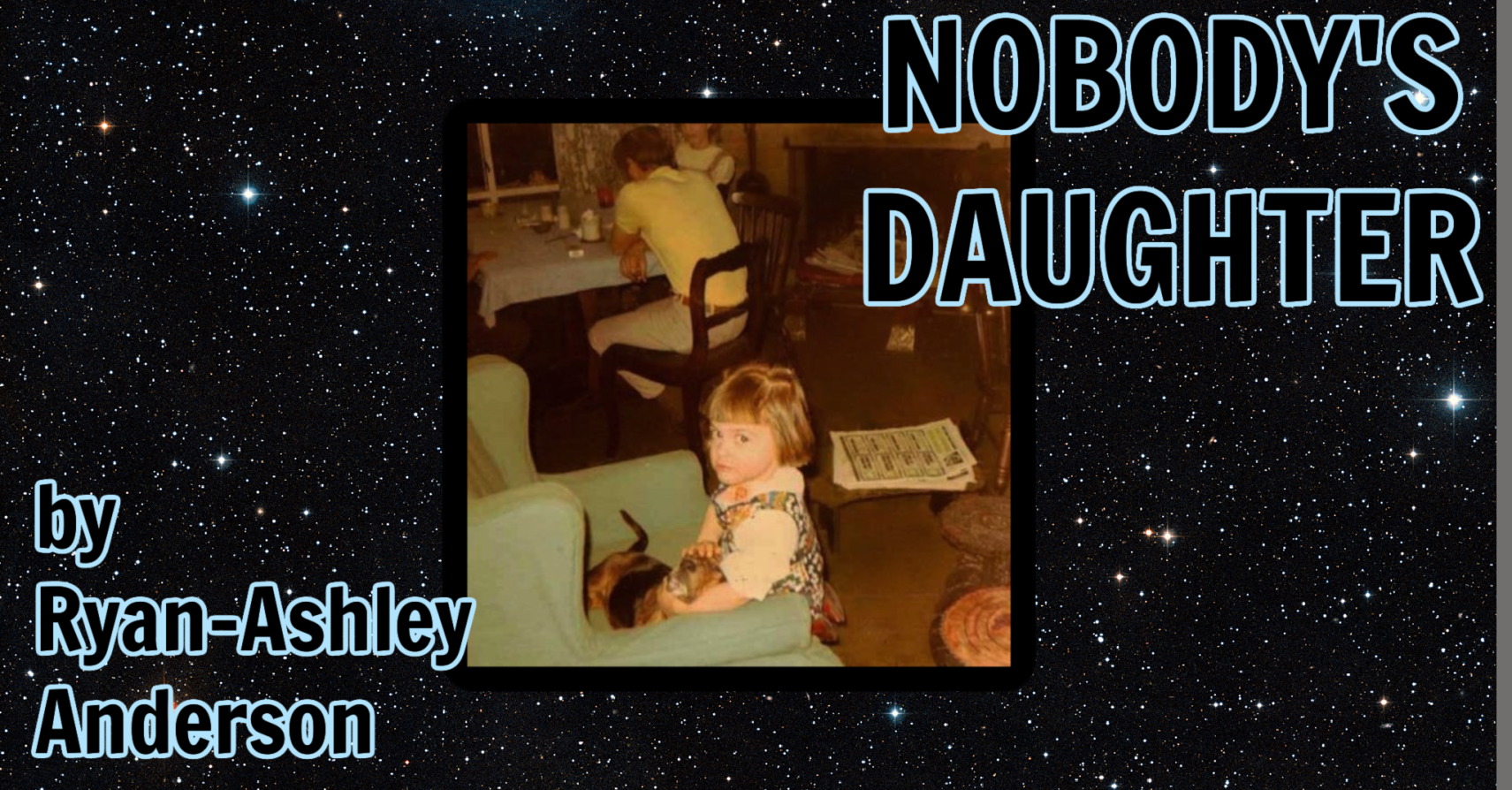

I was almost five years old, it was Christmas day, and I knew something was wrong because I’d gotten everything I’d asked for: a blue and white-checked gingham romper with buttons up the front; black, mid-calf cowboy boots with red stitching; and, most surprisingly, a fluffy black puppy with a bright white chest whom I would come to call Kentucky.

I had never been to Kentucky and am not even sure how I’d learned the name, but I’d tested out several words from my dog name list and determined this was the best one.

A dog’s name should ring out when shouted. “Ken-tuck-yyyyyyyyyy!” I hollered from the back door, “Ken-tuck-yyyyyyyy!” I liked the way it sounded in the wind across the field. Yep, I thought, he would come to that.

***

My mother, her boyfriend Sonny, and I had just moved into an old farmhouse. It sat in the middle of a field at the edge of a trailer park down the gravel road from a lake, just north of the invisible line separating North Carolina from Virginia. They chose Virginia because that’s where Sonny’s three best friends had decided to start a business together, and they were cutting him in. They were dental techs–the fancy word for people who make false teeth–and running your own studio was the only way to make actual money in that profession back then. We were poor, so we moved.

As we drove out of North Carolina and into Virginia, my mom pointed out countless road signs that told us Virginia was for lovers. I whispered Virginia is for lovers over and over again like an incantation under my breath–all the way until we made it to the new house. Maybe if I said it enough times, it might actually come true, I thought. Maybe we could really love each other there. And we did. Our Kerr Lake year was the happiest of my life.

The house was old. The roof was a rusty blue tin that sounded like needles when it rained. The downstairs floor was made of shellacked brick that stayed cool all year long. Mine was the only bedroom. It was downstairs next to the kitchen, and my mom and Sonny slept upstairs in a small loft. The kitchen was tiny, with a half-sized oven, two burners, and a built-in griddle top. There was a fireplace, but there was no insulation. It was perfect.

***

Me, Kentucky, the boots, and the romper were inseparable. So inseparable that, even after days of wear, my mom would have to wait until I was asleep to take the romper from me and put it in the wash. When I’d awaken and realize it was gone, I’d be totally inconsolable while waiting for it to dry. I’d end up wearing that thing for years, only abandoning it once it started giving me a permanent wedgie that no amount of slumping could disguise.

Just a few days after Christmas I came home from school and my mom was acting weird–extra nice–when she greeted me at the door. I noticed a swing inside, hanging from the eaves. It was made from two long ropes and a flat piece of wood, shellacked just like the brick floor. I wondered where it came from and why it was inside.

“Do you want to, maybe, swing on it?” my mom asked playfully as she gestured toward it.

Of COURSE I wanted to swing on it! I was the only kid I knew to have a swing INSIDE the house, and I couldn’t wait to brag about it to everybody at school.

“Where did it come from!?” I asked.

“Sonny made this for you.”

“Really? Why?” I was suspicious considering Christmas had already passed.

“Because he loves you.” She pushed me on the swing, high into the air, in the middle of the house. I pumped my legs, but the whole thing felt strange. Like a trap. And I wondered if I’d get punished later even though the whole thing had been her idea.

“Hey,” she continued, “What would you think about Sonny becoming your dad?”

I stopped swinging my legs. “But I already have a dad.”

“Well,” she pushed, “What if Sonny were your dad instead?”

“How does that work?”

“Sonny would sign some papers saying he wants to be your dad, and after, your birth certificate would show his name instead of Mark’s.”

“Will he want me to call him ‘Dad?’” I asked. I had never even called my birth father ‘Dad.’ I called him by his first name, Mark. I wasn’t sure how I felt about the word.

“I’m sure,” my mother responded.

I thought back to the last time I’d seen Mark. It had been a few months—our final visit together before we moved to Virginia—and as my mom drove us away, he cried, “Ryan! Ryan! Don’t go!” His arms were outstretched, but he ran slowly. Even at that age, I could tell the difference between acting and sincerity, and he wasn’t trying hard enough to fool me. But it didn’t matter. Just hearing the words felt good. I didn’t care that they weren’t real. But then I remembered how my mom told me that when I was a baby and she had to leave for work, Mark would place me, screaming, in front of the window facing the driveway so she’d feel guilty as she pulled away. I didn’t know what to think.

I felt the swing hard beneath me. I felt the boots snug on my feet. The gingham, scratching against my soft skin. I watched Kentucky, asleep on the sofa facing the back window.

I liked this life–this house, this place, how we were together–and I wanted to keep it. So I said yes, and wondered when I was supposed to start calling Sonny “Dad.”

***

My mom loved creative types but craved the stability of a solid career. The two didn’t usually go together but Sonny seemed to fit the bill. They were in their mid-twenties when they met at a houseparty. Sonny’s band was playing, and his stage presence caught her attention. Learning that he also had a career got her hooked. To earn a living, he’d found a trade where he could make use of his creativity–one where his skills in porcelain and carving and color theory set him apart. Back then in the early 90’s, before advanced computer software and 3D printers, dental techs had to be artisans–each tooth a tiny, nuanced sculpture that you had to get just right. It wasn’t the best job in the world but it was enough, and it was steady, and so was he. Once Sonny entered our lives, we were safe, we had a regular place to live, and for the first time, I felt a sense of belonging and possibility that dissolved the anxieties our former conditions had produced.

***

January was really cold. The grass crunched underfoot. ‘Tucky played in the snow. I had started visiting a neighbor when I got bored–the woman living in the house across the field from ours. She managed the trailer park down the gravel road and I’d stop by to help her move rocks around. Something about creating sections for her garden.

One day she told me how, when mama birds were really desperate, they would build their nest right on top of another family’s. They were willing to kill, she explained, to give their babies a safe place to hatch. I didn’t believe it. But then she opened a birdhouse and showed me two nests, one stacked on top of the other. She lifted the top one so I could peek between the layers and, sure enough, the bottom nest was filled with brittle, unhatched, abandoned eggs. I thought about the mama bird. I wondered if she’d ever gotten over it.

***

Winter turned to Spring and all the conversations I overheard in the house centered around wedding planning. Late at night when I should have been sleeping, I’d press my ear to the crack at the bottom of my bedroom door and hope to hear my mom and Sonny talking about it. I’m not sure what I thought I’d learn but I distinctly remember wondering when the whole dad switch was going to happen and if it would coincide with the wedding. Maybe it had already happened. I didn’t know how these things worked. I was looking for clues.

One night I heard them argue. Sonny’s business partners had decided to cut him out of the business, but they had already agreed to be his groomsmen. They could afford to keep him on as a part-time employee for a little while, but he would have to find a new job soon. How would they pay for the wedding? What would he do? Where would we live? My mom was furious and said he should uninvite them, but he said no.

Spring turned to Summer, and Sonny married my mom in the backyard underneath the big oak tree. It was beautiful. My mother wore a faded rose silk antique dress she had found at a thrift store. The sleeves were puffy, the skirt was full, and it seemed to have a hundred pearl buttons going up the back. She couldn’t reach them herself, so she had to be buttoned in and unbuttoned by somebody else. It was probably a young girl’s cotillion dress at one time.

I was the flower girl. I walked down the aisle first after Sonny, and stood beside him waiting for my mom. Sonny was fairly tall–about six feet–and stayed tan all year long. He was fit in a casual kind of way, with greenish hazel eyes, and had a tidy, permed, chestnut mullet. I’d never seen him this dressed up before and he looked funny in his tux, like he didn’t belong in there.

My mom came down the aisle next and she looked like a goddamned angel. There had been a light drizzle that morning–a sign of good fortune, everyone said–and the whole world glowed. The sun streamed down softly from behind the clouds and created a halo behind her. I didn’t recognize either of them, looking so adult and dressed up and respectable.

The couple said their vows, and Sonny gave my mother a gold wedding band that he had made. They kissed, everyone clapped, and then Sonny turned to me. He pulled another ring out of his jacket pocket and got down on my level. He took my little gloved hand, put a tiny gold ring on one of my little gloved fingers, and said something like, “I’m yours for life, too.”

I cried. His groomsmen weeped. And the bridesmaids swooned. Sonny was a good, good man.

***

Sonny couldn’t find work after all, so not long after the wedding, we had to move back to North Carolina. My mom’s drinking picked up again and she began getting jealous of how much time Sonny and I spent together.

One night when she was drinking and just the two of us were watching T.V. in the den, she looked over at me and said, “You know, the only way a new person can adopt you is if the other one agrees to give you up.”

“Your father,” she said, “owed a lot of child support. So I told him that if he gave me a computer, and signed you over to Sonny, I’d agree not to sue.”

She laughed, “Can you believe that!?” and then went to bed.

I turned off the T.V. and walked to the guest room where we kept our IBM. This room would become a nursery just two years later but, for now, the only person using it was Sonny. He’d get high and then spend hours alone with the door closed, creating portraits of Jerry Garcia in Microsoft Paint. I looked at the computer and wondered how much it weighed. How much it was worth. I called Mark to ask but he did not answer. I went into the garage where ‘Tucky lived and cuddled him for a while in his dog bed before going to my room.

***

A couple years passed, my mom was pregnant with my sister, and the guest room had become a nursery. It was a Friday and she unexpectedly picked me up early from school. We suddenly needed to go visit Sonny’s mom a few hours away in the mountains, but she didn’t say why. We’d need to stay a couple nights to make the trip worth it but, unlike previous trips, we couldn’t afford to pay someone to watch Kentucky. With a new child on the way, my mother was worried about money, so instead of boarding him or hiring someone to watch him, she put Kentucky on a chain behind the house. She filled bowls with food and water. I cried and begged her not to. The chain wasn’t very long and I was worried. Other neighbors let their dogs roam around and they weren’t very nice. What if they picked on him and he couldn’t get away? She laughed off my concern and promised that he would be fine.

While my parents packed, I walked door to door begging neighbors, tearfully, to keep Kentucky while we were gone. I had a terrible feeling that something bad would happen while he was out there by himself and even asked people I’d never met before. I was desperate. But they all said no. I insisted my mom let me stay home alone with him that weekend, but I was eight and that wasn’t allowed.

I refused to pack a bag, so my mom did it for me. She forced me into the car and promised to punish me for being insolent when we returned home from the trip. I didn’t care. I was devastated. I couldn’t stand the thought of ‘Tucky thinking I’d left him.

My mom put the car in reverse and began backing away from the house. Everything around me went in slow motion, while everything inside me raced. My stomach churned, my heart beat out of my chest, and big, hot, tears flowed down my cheeks. I watched from the back window as we drove away and strained to see ‘Tucky from the road, but I couldn’t.

When we returned home from the weekend, I ran out of the car as fast as I could. I didn’t understand what I was seeing at first. Bowls of food knocked over. A chain lying limp in the grass. Kentucky, nowhere to be seen. I made the same neighborhood loop, knocking on every door, asking all the neighbors if they’d seen him, but nobody had. I walked home slowly, then stood outside in the backyard until long after the sky had turned black and the lone street light had turned on. I looked toward the tree line and called, “Ken-tuck-yyyyyyyyyy! Ken-tuck-yyyyyyyyyy!” But he didn’t come.

***

I made flyers on the computer. I didn’t know how to get ‘Tucky’s photo on them, though, so I used clip art to search for a dog that looked something like him, then described him in detail. I added our phone number and said, “PLEASE CALL!” in really big, bold letters. I didn’t have any reward money to offer, so instead, I promised to do chores for anybody who could point to his whereabouts. I printed them out and put them in all the mailboxes around the neighborhood. When nobody was looking, I peered into windows and fenced-in backyards, hoping to see that Kentucky was stolen rather than lost.

After getting the fliers, one of the neighborhood kids called to tell me they’d seen him floating in the pond across from my house. Another called to say her father had shot him while hunting in the woods. I was afraid to go into the woods after that. And afraid to look at the pond. I tried not to fall asleep because I had started having a nightmare.

In this recurring dream, I’d be lying in the bathtub with my eyes closed and the water would feel, suddenly, full of fur. I’d open my eyes and ‘Tucky’s skin would be on top of me in the tub, empty and flat as a bearskin rug. I’d try to scream, but when I opened my mouth, the fur pushed inside me and no sound came out.

I had insomnia at night and was riddled with anxiety during the day. I was a wreck and eventually, had to move on. I stopped looking, but sometimes I’d still go into the yard late at night and call his name, just in case–“Ken-tuck-yyyyyyyyyy! Ken-tuck-yyyyyyyyyy!”–but he didn’t come. And he never came again.

***

Time wore on. My sister was born, we moved again, and I, eventually, moved out. Then, in my early twenties, my mom and Sonny got divorced. Nobody told me at first, but I had stopped hearing from him and his family and I started to wonder. My little sister eventually broke the news, right before Christmas. I guess everybody just thought I wouldn’t notice and they could avoid the subject altogether. My sister–his biological daughter–still got presents from Sonny’s parents that year. I did not. And, just like that, I heard Sonny had a new girlfriend with two boys, and I got this sinking feeling that he had decided not to be my father anymore.

***

By the time I was in my mid-twenties, I hadn’t spoken to Mark, my biological father, in over twenty years. My sister was a teenaged heroin addict, I was an alcoholic, and I had dropped out of school. I was estranged from my mother and hadn’t heard from Sonny for the better part of a year. I wanted to preserve the relationship with him–I needed to preserve the relationship–so I called him, crying, drunk, and begged him to keep being my dad.

“You’re the only dad I’ll ever have!” I argued, “You are my one shot at this! I don’t get another chance to be a daughter! Can’t you just pretend that I come to mind, even if I don’t? Can’t you just lie to me?”

I bargained, “All you have to do is put a monthly repeating call reminder in your calendar and then you don’t even have to remember! Just pretend, for like ten minutes once a month to care about what’s happening in my life.”

He said he would.

But I didn’t hear from him. Another year passed and Christmas, once again, was just a couple months away. I reached out and reminded him that if he couldn’t manage a monthly call, not to bother sending me an obligatory holiday text. He said OK, but nothing changed, and then my phone pinged on Christmas.

“Merry Christmas to the best daughter!” the text read.

The words were like stones in my stomach. I took a swig of wine and wrote back, “I told you what the deal was. You don’t get to reach out to me at the holidays if you don’t talk to me the rest of the year. It’s just too painful a reminder of what’s missing from my life.” He didn’t respond, and I didn’t hear from him again.

But I did hear that he’d decided to marry the woman with the two boys. I wondered if he would promise anything to his new sons at the altar, and wondered if he would mean it.

I erased Sonny’s number from my phone, Googled How to get parents removed from my birth certificate, and drank down the last of a bottle of wine. I thought about enrolling in cosmetology school, but decided to go to AA instead. I wanted to tell somebody, to ask for help, to cry, but didn’t know who to call. I was nobody’s daughter now.