The grouchy buildings of The Six, the dirty snow’s hectic dance – it was all far beneath me now. Keely, my thirteen year-old niece, had taught me to call Toronto “The Six.” She reeked of perfume that seemed to combine garbage with vetiver and beets but was surely expensive. The smell emboldened me – rot and beauty enmeshed. It blurred my warring worries and desires.

So far, I loved flying. The soothing keen of the engines; my seat a mini-empire, a customizable media-pod; the shiny dossier in my seatback pocket pregnant with a secret I was itching to share. I loved, instantly, the neighbours I was nestled between – a rumple-suited man with a sparse ring of gossamer hair, a woman with a large mole on her cheek in head-to-toe baby pink (sweat suit, eye mask, neck-pillow), both asleep since before we taxied out. I loved, too, the slim aisle of knobbly carpet between the banks of seats, the flight attendants gliding along, resplendent, serene, behatted.

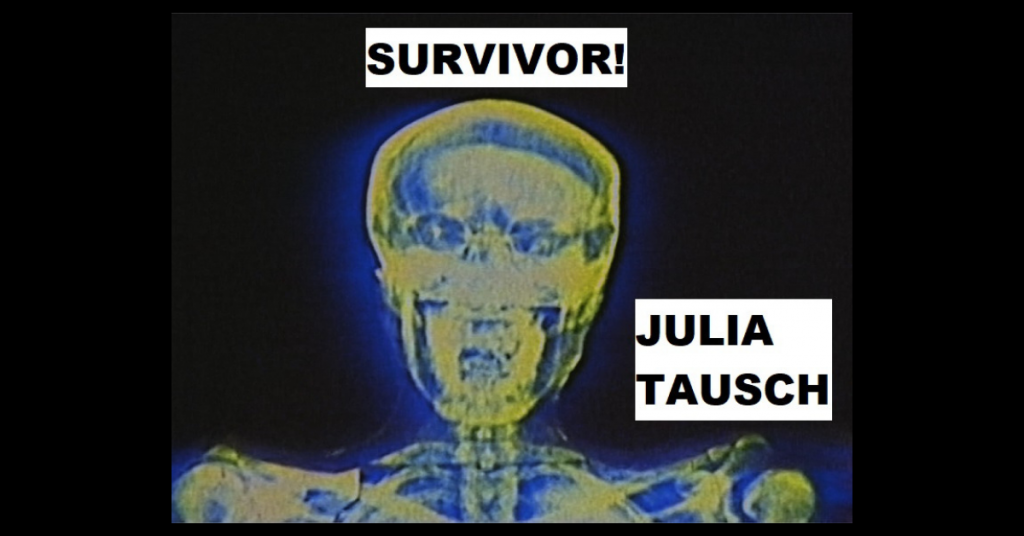

I had to stop thinking like this or I might talk like this on TV. No one liked the type of person who said “behatted.” Partly I’d been spending time with Keely to emulate her guarded vocal fry. It sounded so lovely, like she had countless better things to do than finish her words, let alone her thoughts. If Keely had been chosen to compete on Team Togorna upon the pristine beaches of Laos she would simply drape her bikinied body over a log and wait while the other contestants wept snottily, suffered night terrors, sprained their ankles and yelled about rice. Then she’d saunter home with the million dollar prize.

But it wasn’t Keely with seven bright bikinis folded into neat knots in her backpack. It was me. Yes, it had been her who’d helped me pick them at some ungodly store on Yonge. Street where the squealing staff descended like jackals; it had been her who’d insisted upon the very thorough waxing her clique swore by. At thirteen. But this had seemed like a good time to follow her lead.

Over post-wax salads I’d spluttered “I can’t go! Who’ll take care of Nana? The new meds make her so withdrawn. She hardly talks and when she does…she told me about her and your grandpa’s final fight last night as if it were yesterday! If we just knew what it was, I’d feel better, but…Your mom can’t look after her, she’s so…busy. She doesn’t –”

Keely cut me off. “Oh my god,” she said. “Suzy? Don’t even stress.”

Now here I was with my bathing suits. What Keely had said had dug its little nails into my brainstem. I held a picture in my mind of her face when she spoke those words in the jubilant light of the juice bar: blank save for a crinkle of irritation and maybe, even as her eyes flicked back to her phone, a slight clench connoting concern. Hard to tell; therein lay the power. I carried it with me as we hurtled toward Bangkok. I would not stress.

An hour in I ordered sparkling wine and reviewed the waivers I’d signed, the big font disclaimers, the glossy photos in my dossier. The beach, the host, huts and tents from seasons past, old teammates hugging, robust again after their emaciating ordeals. Soon this would be me. In Bangkok I would meet Team Togorna, board a private jet, and fly to our secret locale. I sipped and the bubbles exploded, tiny pricks of pleasant pain against my tongue.

Last I’d drunk sparkling wine had been at Keely’s mother’s – my sister Kendra’s– wedding. During the dancing I’d plucked a ball of spun sugar off the cake and held it as I gazed out the window of the restaurant Kendra’s new wife owned – fifty-seventh floor of a bank building. I wept because the highway-coloured lake and red-eyed towers were at once so achingly beautiful and familiar as death; my sister had been, in her sparkling dress, like something of spun sugar herself; our mother wouldn’t take her dark glasses off; and Keely had ignored me all night in favour of some new goth cousins. I could never have imagined then slicing through that smoky sky.

But now! My seatmates snored lightly, the window gone the fuzzy gray of no-time. Service-summoning dings offset the engine’s low drone. Again I scanned the disclaimers. I didn’t do great on no food; probably I’d cry a few times. But no sleep? Please. I spent most nights awake, inhaling my shows (competitions only – you can have your teen moms), recording strategies in Excel. By week three I could predict the final two.

Some nights I drove the five minutes to my mother’s, held a mirror to her sleeping face, and waited for the fog. Just in case.

Other times I went to the 24-hour gym. At thirty-seven I had a slamming body in spite of my dead-end desk job plus a brain that pulsed with the will and tools to win.

Don’t even stress.

When I closed my eyes, I saw it. The crew erecting their equipment like spindly totems behind a scrim of blowing sand. The wavy-haired host in his cabana, studying the games and their rules. The craggy, reddish cliffs hugged by humps of verdant jungle, blurred at the edges like so much smudged pastel. The elegant swath of sea – now turquoise, now beige and irate. Though my journey had just begun, I could see, too, the end, as it actually came to pass. When I stood for hours on a stump – no mother on my mind, abs engaged, ignoring the sweat that snaked around the buttons of my sun-singed spine until immunity was mine. When I addressed the council for the final time – just as I’d rehearsed back in The Six – the steamy jungle redolent with freshness and decay. When they listened and I won and could, at last, make it rain.