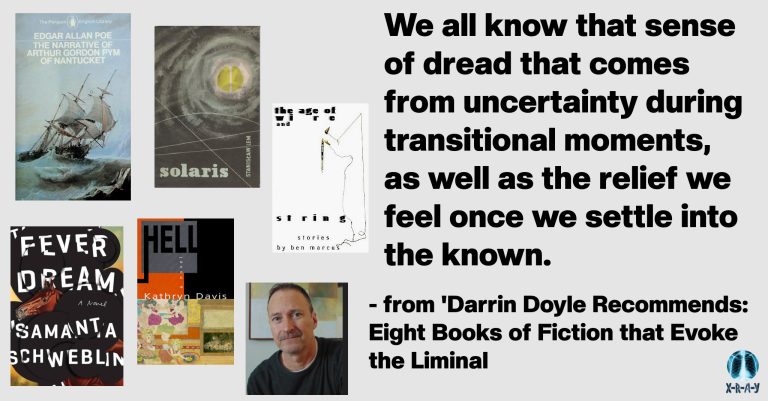

DARRIN DOYLE RECOMMENDS: EIGHT BOOKS OF FICTION THAT EVOKE THE LIMINAL

Opening your eyes at night, unsure of where you are, half-dreaming, half-awake…staring into the darkness of a living room, thinking that the shadow near the door might be a man…or a coat rack… the tremble along your spine as you hear the voice of a deceased loved one on your voicemail…the uncanny sight of a mannequin that may or may not be a living person. We all know that sense of dread that comes from uncertainty during transitional moments, as well as the relief we feel once we settle into the known. Below are a list of fiction books that