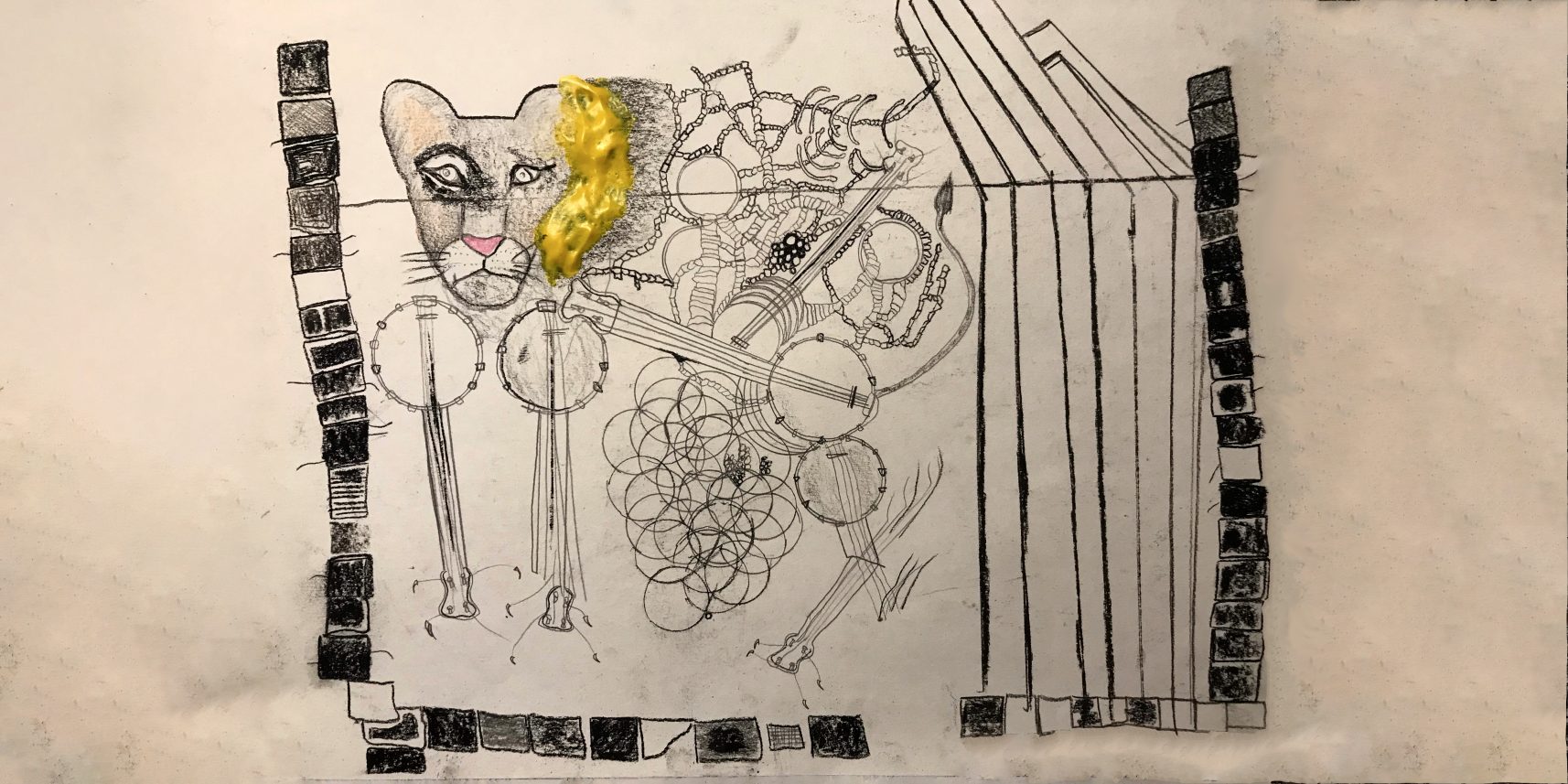

LOW GAS AND A LION IN THE BACKSEAT by Hannah Gregory

My hand lives in her belly. That belly has a tumor the size of a banjo. I like to think my hand keeps her company, playing a soothing song on her tumor banjo whenever she cries in pain. I use my one hand to play my non-tumor banjo for her, my actual banjo, like hum-di-bum-hum-di-dee-hum-di-bum-hum-di-dee. No chords because, hello, one hand over here. My girlfriend Tracy is always yelling at me for getting a lion, but Theory: Is it really about the banjo? Tracy refuses to help me with the chords so she just hears me singing in Open G…