Three weeks before harvest season, Grandfather started shooting down corn stalks from the third floor of our rural manor. Every half hour, he asked me to run downstairs and get him some more ammunition. When he decided that wasn’t efficient enough, he told me to get the grenades, which he strapped to turtle doves and released into the valley. He trailed yards of gasoline all along the lodgepole pines, and he launched the lit match from the tip of a harpoon gun. By the time harvesting season started, the crop fields looked more like a battlefront.

I was the one who caught the doves for Grandfather. I brought them home in a wide basket and secured them in the cages upstairs. The morning I opened the basket and noticed a fledgling, Grandfather was already making his rounds. He followed my line of vision and, before I could flinch, scooped up the young dove in his palms and tied it to a grenade. I asked him what he was doing. I watched him pull the pin and toss the bird. It thrashed in the air, becoming tinier in the distance, before combusting into ash and smoke. He declared that he had waged war against the forest.

Grandfather went into the storage shed and started pulling out concrete bricks. He placed them around the outside of the house, one by one, with a rifle strapped to his back. When he ran out of bricks, they started arriving in shipments. Hitting rock against rock like a caveman, he carved spikes along the house corners. He stationed bear traps and artillery within the barrier, which he launched every Wednesday into the thinning trees. After he was done, he crawled on his stomach for hours to uproot each blade of grass.

Almost breathlessly, he raved to me that he had done it: He had separated himself from nature once and for all. I pointed out that we ate from nature before a light flickered in his eyes and I cupped my hand over my mouth.

That evening, he piled whatever produce he had left in storage with the remaining cropland and set it alight. He sat me down by the bonfire and we watched it burn until sunrise. Afterward, it seemed to be business as usual. Yet as the week passed, we were driven mad by the famine. Grandfather was lightheaded and, when launching gunpowder into branches, fumbled with the machinery. Crazed, I went to the bear traps when Grandfather wasn’t looking and ate from the deer carcass. But by the second week, Grandfather barely even noticed the cavity in his stomach, and by the third week, he finalized his plan of attack. Should the forest not surrender by the end of the month, he would flood bleach into the river, which would carry downstream and deliver a close to his war at last.

He was counting his barrels by the shed when he saw movement in the upper window. He rushed upstairs to find the doves fluttering away and me with my hands frozen on the locks.

Down by the riverbank, Grandfather tied me to a tree as if to a crucifix and trudged home for the night. Each morning, without veering to look at me, he came to line up the barrels along the gravel. Neither of us spoke a word.

Grandfather woke up dizzy. On the first morning of the new month, he died of starvation in our home. Strand by strand, I used the branch to chafe off the rope. Then I limped over to the side of the road, started walking, and never turned back.

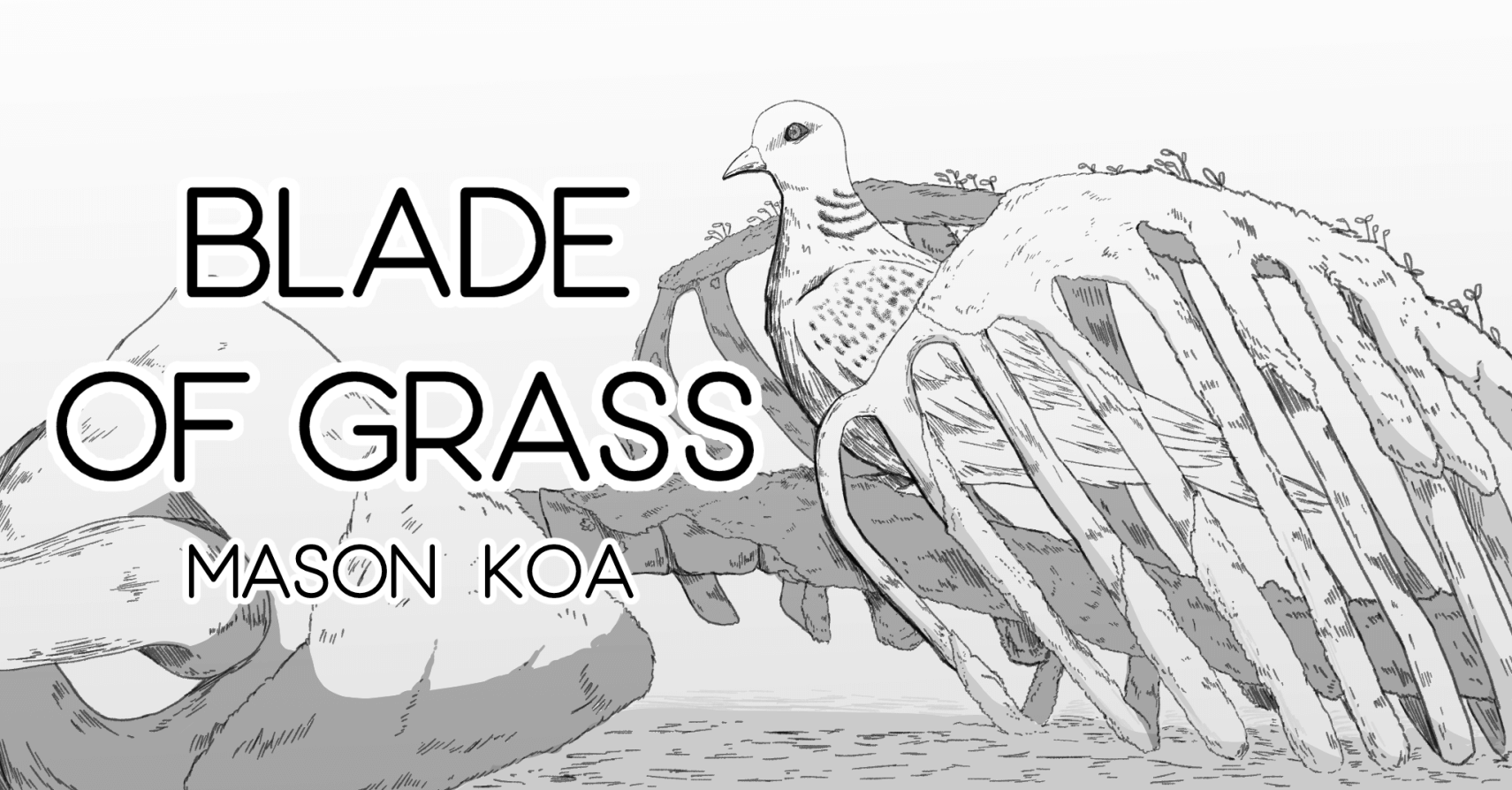

The lichen came upon the house first, taking hold within a few years. Then came the vegetation. The east face of the wall fell with no one there to see it. One day it seemed to be up, then gradually the bricks must have tumbled down onto the grass. Then came the animals. The turtle doves flew in through the curtains and made nests in Grandfather’s ribcage. Their chirps resounded off the valley and fields. From the chambers of his flesh came a sweet, victorious song.