Pendulum A has a mass of 138 and hangs near the front entrance taking souvenir photos of families who come through the Michigan Science Center. She’s got a certain spunk—which you’d think would be good for business—and cheeks that stay red long after she’s blushed or come in from outside. As people pass her, she says in a peppy tone, “Photo? Take a photo?” She holds the camera up to her shoulder and hovers it there, ready to pounce even as she gets rejected again and again. Few stop, because why would they, they all have a smartphone. Those who stop do so because she’s magnetic.

Pendulum B has a mass of 176 and hangs in the open-floor show area, a pit surrounded by stairs where people sit and watch him turn powdery substances into gels as part of the super absorber demonstration. He wears a white lab coat and safety goggles over hair that could use a trim and keeps the coat sleeves rolled up even though it lets his tattoos peek out and the management once told him the company policy doesn’t allow visible body art. Given that the last two yearswiped so many of his coworkers away, he figured there was no way he’d be fired over this. He was one of only two show leaders left, so he pushed against the policies a bit. But he likes this job of introducing science facts to little kids and their tired parents. It even provides credit for the degree he is pursuing in Physics at Wayne State. Better late than never, at least that’s what he told his mom.

To which she said, with the sound of a lump in her throat, “Your father would have been proud of you for this.”

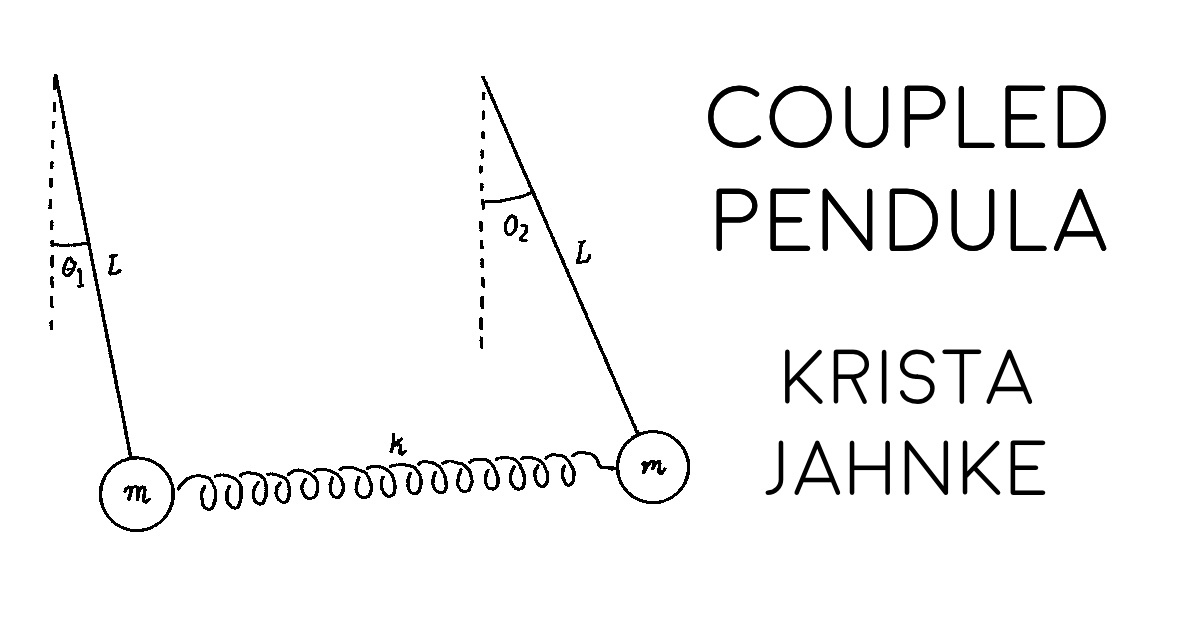

The spring coupling the two pendula is their shared Sunday afternoon shift each week. It’s the only time their schedules overlap.

Pendulum B isn’t sure why Pendulum A isn’t around more, but maybe today he’ll ask her. Ask her, like, what she does outside of the Science Center. He’ll say something chatty and non-threatening, maybe if they overlap on their breaks for lunch—if she eats lunch today.

She doesn’t eat during most shifts. This is because she likes to eat at home while streaming live on TikTok. It’s called #EatWithMe. She hits the button to go live and slowly eats something. It could be anything: an apple, a banana, a small granola bar. Comments fly in, encouraging her. It’s helping, and it’s healing in its way. It motivates her to put food into her body, this weird online community. It makes eating a participatory event, a spectacle. Her Dad even helps sometimes; he will hold the camera for her if she asks him. She thinks it’s beautiful and has told him so, so he does what he can to understand it.

The total kinetic energy in their interactions appears to be greater than 0.

Sometimes he’ll see her smile when he gets a louder-than-normal crowd reaction during shows.

Sometimes he walks past her while she’s hawking photos, and he says something dumb, like, “Rocking that Nikon once again I see!” Nerdy, but he makes her laugh.

The potential energy of the system—the two of them—could only be determined if he can get her alone somewhere.

He imagines them twisted into bending shapes, spring-loaded, gravity-defying. But first he has to talk to her, more than a stupid quip.

He makes Attempt 1 at 1:16 p.m., Sunday, March 30. He approaches slowly, from the northwest, and she does not see him coming, since she is facing southeast as she sits in the small, fluorescent-lit break room looking at her phone.

“Hey,” Penduluma B says. “Amber, right?”

“Yeah,” Penduluma A says, setting the phone down. “And — Brandon? You do the shows?”

He gets his sandwich from the fridge and stands there, unsure if he should sit.

“How come I only see you here on Sundays? Is that the only day you work?”

“I do real estate photos during the week. That’s my other gig.”

“Oh, got it. Are you from nearby?” She looks at him like that’s a weird question.

She finds it suspicious when guys ask where she’s from, like, are they asking about her race or ethnicity or what? A lot of the time, they are. “I’m in Southwest. Like, past Corktown. You know?”

“Like, Mexican-town? Near the bridge?”

She picks her phone up again. “Yeah, sort of. Are you from Detroit or the ‘burbs?”

He sits across from her. He’s been standing and it feels awkward.

“I’m living in Midtown now and go to Wayne State. But yeah, I’m from the suburbs. From Royal Oak.”

As he sits, she stands and walks to the water dispenser on the other side of the room and grabs a cup to fill. She drinks the water and leans against the counter and stares at him intently while she drinks.

“I hate Royal Oak,” she says. “I went to a bar there once and every guy there was like a frat boy, dancing too close. So much cologne. No offense.”

“None taken.”

He can understand both the sentiment that Royal Oak bars are kind of skeevy and that the guys at those bars would want to move close to Amber on a dark dance floor. He would like to. He tries not to show this on his face.

“Biomedical physics. This job is kind of perfect because I get a credit for it.”

“That’s dope. I didn’t go to college.”

“Maybe you don’t need to for photography, huh? But it’s not too late. I mean, I didn’t go right away either.” Understatement.

She puts the cup in the garbage and walks to pick up the camera, which she’d left on a seat at the table.

“This is just a side gig.”

“But I thought you said your other job was also photo-related?”

She doesn’t say any more in response, instead she goes to the door and throws a line back into the room. “Well, photos don’t take themselves. See you.”

Evidence suggests the presence of a spark, though dim. The shift has three hours to go. Attempt 2 will be forthcoming.

His post-lunch shows are at 2 and 3 p.m.. He gets his show caddy ready, but he’s distracted, replaying Attempt 1. The afternoon shows are the ones where he torches a balloon. The kids especially enjoy it. It involves fire and loud popping sounds, what’s not to love. But he realizes once he’s on the floor that he left the tiny fire extinguisher that he has to keep handy for accidents in the supply room. He hauls off to go get it, and on his way back, he cuts across the front of the exhibit area, going out of his way so he can pass her and enact Attempt 2.

On the way, he passes the coupled pendula display. It reminds him of something, the way the tiny silver balls remain in opposition, side by side, swaying past one another. One wiggles and then stops, then the other wiggles and then stops; whenever one silver ball comes near, the other is repealed away. What does the wiggling mean, and what does the stoppage indicate? How do they both keep perpetually moving, while also pausing over and over to wait, just to let the other pass by, never matching rhythms?

He shouldn’t stare long because his boss caught him there a few weeks ago and looked at him funny, asked him what he was doing.

Thinking about my show, he told her. That was partly true. He was also thinking of the fight he and his dad had the summer before, the one about truth and information, about what facts are and how the scientific process works.

Now, he keeps moving, forging a path through the enormous plastic heart exhibit, which beats with a steady, piped-in audio, a puh-pum rhythm. Kids clog the walkway as they repeatedly push the buttons inside the heart’s chambers, trying to get different sections of the heart to light up around them.

“Sorry, kids,” he says, stopping to push a button to show them its uselessness. “This doesn’t do anything. This thing is broken.”

“Aw, man,” says one, a kid wearing a winter scarf even though he’s inside and it’s March and not that cold anymore.

“Yeah, I know. But hey, I’m a scientist here and there’s a show coming right up, so you should come to that anyway.”

The kid’s eyes go to the extinguisher. “Does it include fire?”

“Totally. Come see it, I’m right over there.”

“And you’re like an actual scientist?”

“I am, yeah, kind of. I’m still in school but I’m studying to be one.”

“Cool!” The kid turns to yell to someone outside the heart. “Dad! This guy is a real scientist!”

He feels happy each time a kid does this :gets into a conversation with him and seems genuinely impressed. It’s unclear why it touches him so. Maybe it’s just a weird way to be flattered, impressing little kids, but it feels like something else, something to do with being almost 35. He wouldn’t say he thinks about fatherhood, at least he didn’t until six months ago. Now, random kid encounters like this make him think of himself as a kid and his own father back then—his soft, plaid, button-down shirts. His grimy Michigan State ball cap,. His affinity for watching the Red Wings in his chair after dinner with a Labatt. His laugh when they watched shows together that they both liked, stuff like Seinfeld and Frasier.

Also his casket, so heavy, and his ashes, silty and grey, and how they didn’t blow into the lake like he thought they would. Too much of them (of him) wound up scattered on the bottom of his cousin’s Pete’s old rowboat.

His mom was pissed about that. He told her it wasn’t a bad place to be immortalized, bopping in a rowboat in the perfectly clear Lake Huron waters, forever tied to the dock for sunrises that were so gobsmacking they would make even a faithless man pray.

She watches him in the giant heart holding a tiny fire extinguisher, and it looks like he might cry. He looks young, vulnerable even. She picks up her camera.

He’s still sort of half-smiling from his interaction with the kid as he hurries out of the heart and toward the front entrance, where Amber is standing very still.

He doesn’t realize her camera is trained on him until he’s nearly upon her. Through the viewfinder, she watches him approach.

“Oh, hey,” he says, stopping. He holds the fire extinguisher up to his face as if to say, This, this is why I’m here now, walking past.

“Photo?” She clicks the button. “Sorry, no chance to say no now! That’ll be $9.”

He laughs and grows still, looking at her as she looks at the digital viewfinder on the back of the camera.

“Can I see it?’”

“No,” she says. “You haven’t paid.” She points to the kiosk in the corner. “Go pay after your shift.”

“Yeah, I get a commission for every photo. Plus, really, it’s a good photo. You’re kind of smiling like you have a secret. You look good.”

This comment hangs between them, and yes, he senses something.

“Why would I want a picture of myself?”

“Trust me, it’s a good picture. You’ll like it. I’ll go get it for you if you want, and you can pay me back. I’ll meet you out front after we close.”

He can’t concentrate during his show. He almost pulls the wrong trigger on the torch, which is really just a glorified lighter, while he’s showing a small child who volunteered from the audience the fire mechanism, and then he pops one balloon too early, ruining the reveal, forcing himself to start over. He’s too old for this shit, this feeling all woozy about a chick.

Let’s assume it’s possible to find the value of such that A will draw closer to B. Maybe he should ask her out. Or maybe she’d find that too forward. Maybe he should get her number and then text her for a while, which seems a safer entry ramp to something. His last girlfriend he met on a dating app, and the one before that. Tactics for real life elude him. Theories come to him as he packs the caddy up after the last show. He puts it in the back and grabs his windbreaker and heads to the front of the Center. Amber is waiting there like she said she would be.

“Here it is,” she hands him the photo. “See? What’s this smile about?”

“I don’t know,” he says. “I think maybe I was remembering something.”

She’d hoped he’d admit the smile had something to do with her, but alas. “Hey, this is kind of weird, but do you think you could drive me home?”

He stares at her, calculating.

“Did you walk here? From Southwest Detroit?”

“I take the bus. I could use a ride though. I’ve seen you in the parking lot in a car that looks like it runs and all. Would you mind?”

He feels a tiny deflation, a questioning about what she really wants. Him? An Uber driver? But either way, she’ll be in his car. It does sound good.

He leads her to his car and thinks about equations of motion. He can think of only two possible solutions to the problem set of

how to extend his time with her and not have this encounter end abruptly with her leaving his car. Make a pit stop or get lost, and it would be close to impossible to get lost. As they head south down Woodward, trailing the red and white streetcar and dodging jaywalkers, he makes Attempt 3.

“You hungry? It’s early, but we could stop at Coney.”

“I’m a Lafayette guy myself.”

“Yeah, I hardly even know you, but I knew somehow.”

They go to American and order dogs and cheese fries. They sit on the stools and watch the workers flip meat and hustle back and forth. He remains still on his stool, but she swivels on hers. The food arrives quickly, and he eats a mustard-laden bite of dog and thinks of the last Tigers game he went to with his dad. It was just the previous summer, and they’d stopped after the game at Lafayette, right next door. It had been a good day; they’d steered clear of conversation topics outside of sports. He wonders if anyone is sitting in the booth where they sat.

“Why did it take you so long to talk to me?” Amber pushes the fries around without eating them.

“Were you waiting for me to talk to you?”

“Yeah, kind of. I saw you looking at me. And you do that a lot you know.”

“Answer my questions with another question.”

“Yeah, you’re a nosy fucker.”

He snorts. “I guess I am. Are you going to eat those fries?”

She pushes the plate away. “I’m not that hungry.”

“You’re not like, anorexic or something?”

“Jesus. You shouldn’t say it like that. Anyway, a lot of the time, I eat on camera.”

“What does that mean, ‘on camera?’”

“Like this.” She takes her phone and props it in front of her, standing it up against a sugar dispenser. She flicks on the TikTok app and then starts recording herself.

“Hey everyone, it’s Amber. It’s time to eat. I’m having some chili cheese fries here with my coworker Brandon. Let’s eat together.” She picks up a fry and wipes it through the greasy chili and cheese, loads it up, and then places it in her mouth while making direct eye contact with her camera. She does this for a minute, then turns off the camera.

“You probably think it’s weird.”

He doesn’t have TikTok and doesn’t understand at all how it works. But there’s a warm feeling in his arms, that she has revealed this true thing about herself. She didn’t have to do that.

“I don’t know if it’s weird, I don’t really do social media. Do people like this stuff?”

“Yeah, tons. I have 27,000 followers.”

“Damn, you’re like, famous.”

“Only a little bit. But I do make some money from it. You could probably be TikTok famous if you did some of your science stuff on there. People like to learn.”

“Huh, I’ve never thought about that. I don’t know what I’d have to teach people. I’ve still got a lot to learn myself.”

“Don’t we all?” She eats one more fry then pushes the plate away. “I need to get to a house in Indian Village for a photo shoot. You ever been over there? Nice houses, really pretty. Really big.”

“Oh sorry.” He takes a bite of dog and swigs his pop. “We can go, I’m all done. Let me pay up.”

She stands from her stool and pulls money from her purse. She leaves it on the counter and yells to the guys working, “Thank you!” She walks to the door and steps outside into the sunlight. The sun beams into her skin and brings her a bad idea.

He waves goodbye to the guys and follows her, then walks past her to approach the windows at Lafayette. Through the window, he sees it: the booth where he and his dad ate after the game last summer. There’s a man sitting in it now, eating lunch. Brandon turns to look at the street so as not to disturb the man, who seemed to see him and sent him an angry look.

“Are you OK?” Amber touches his arm. Brandon is staring at the road, still, with another look on his face, like he saw a ghost.

“Yeah, just remembering something. Let’s head out, sorry.”

Once they’re in his car, she touches his arm again, where she can see his tattoo now. A rowboat. “Hey, I was wondering if you’d come with me?”

“To the photo shoot? You need a ride there, too?”

“Yeah, I do,” she laughs. “But it’s not just that.”

“No. I thought you could come in. See the house, and you know, hang with me.”

He notes this with glee, adds it to the probability of symmetry in their system.

“Yeah, sure.”

She looks for an address somewhere on her phone and then, after asking for his number, texts him an address.

He has her number now. He should forget about his dad. It’s a 10-minute drive. He points his car east, away from downtown, toward the neighborhoods where canals cut through people’s backyards and old stately homes sometimes border fully burned-out structures or abandoned, overgrown lots.

“My dad actually grew up not too far from there,” he said. “In Poletown.”

“Did he ever show you the exact house?”

“No, actually, I don’t think it’s there anymore. It made him sad to talk about it.”

“Yeah. He died in October. Of Covid.”

“Oh, geez. I’m sorry, Brandon.” She touches his arm again.

The equations soften in him. He can’t explain how or why. He feels science slipping from his pores. Focusing on calculations was a mistake. A woman is made of flesh and something like a vapor, an unknowable collage of emotion. It’s scary as hell because there is no way to quantify it, especially for a woman who has opened her wounds. He cannot compute the right moves. He looks at her now, and he’s looking at him, making her own judgements, her own computations. What does she see? He should pause and reassess but it’s like he can no longer hold back. He starts to ramble. He tells her how in the ‘80s, the city bought his father’s house: eminent domain to build a car plant. His father was forced to move away. First to Warren, with so many other Polish Catholics, and then Royal Oak, where he met his mom and got married and had him. They put him in private school, signed him all for T-ball, all that. He was a pretty good student, before pissing away most of his 20s trying to be a musician, a drummer. How his parents were happy, for the most part, until the pandemic made his Dad addicted to the wrong news sources and then paranoid and angry.

He’s spilling it all to her as she sits so quietly in his car, now in shadow of the giant house she needs to photograph, someone else’s picture-perfect life shined up inside, ready for the spotlight. He explains how his mom is bereft since the death, of course she is, but it’s too hard for him to see her, she’s always crying. He is a bad son; he knows he should see her more often. Amber listens and waits next to him, and her stillness is stunning in its completeness.

“Sounds like you’ve been through a lot,” she says finally. She’s holding her camera bag and her purse and has a hand on the door handle.

A rush of shame hits him. “I’m sorry, you just wanted a ride and I’m like, unloading all this on you. Sorry.”

She shifts a little next to him. “Well, I told you about my thing, the eating. I guess this is yours. We’re even now.”

“Yeah. You’re all messed up about your dad.”

The air between them is rife with a sharp, static charge. He’d always felt her to be magnetic, but now he is uncertain what it is, a push or a pull, attraction or repulsion, the positive side or the negative. She must feel it too. The space between them seems to be collapsing in on itself.

He’s not leaning back. She waits. She moves an inch closer. He doesn’t look up at her. He’s looking at his hands in his lap, then out the window and down the street, toward the way they came. Anywhere but at her.

She leans toward him. He can sense her leaning his way.

He clears his throat. “Look, you probably should go and get the photos, huh? And I have some studying to do, so…”

She pulls back. “Yeah, I should. The photos don’t take themselves.” He doesn’t laugh at her joke from earlier or he doesn’t notice.

“I’ll see you at work. Next Sunday?”

She opens the door and steps out. “Yes. Next Sunday.” The door shuts behind her with a snap. She stands with her camera in her hands, her eyes on the hood of the car.

The energy they’d manifested dissipates. It floats heavenward from the space that’s now lost between them.

At least until Sunday comes again.