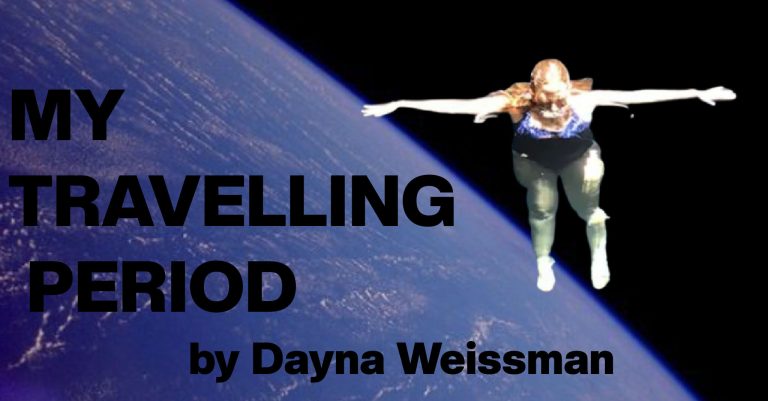

MY TRAVELLING PERIOD by Dayna Weissman

They’ve brought in a man with a lie detection kit for the reunion of the seventh season of my second favorite reality television show. They’re getting all of the ladies wired up to his machine and asking them if they think they are the hottest lady in the office. The “office” is the real estate firm where they all work as real estate agents. All of the ladies say, no, they do not believe they are the hottest lady in the office. The machine goes off every time. It’s good to believe that you are the hottest lady. It’s gotten