I.

My mother tastes like the peanut butter sandwiches she made when I refused a homemade meal, Chai-spiced tea to soothe bronchitis, and a sprinkle of powdered sugar on brownies and banana bread. Her taste is stolen bites of cream cheese mixed with sugar as we make pumpkin cheesecake, steady instructions for achieving the streusel on sweet potato casserole, and chocolate frosting on birthday cakes.

In the time of new prescription refills, when she sleeps for days on end, sugar and fat dance on my tongue. It’s a momentary high from stolen food to fill an emotional void, whole boxes of Pop Tarts and packages of Oreos stuffed down after school, the wrappings stashed beneath my sheets. When food is scarce, I taste a concoction of saltines and apple jelly. The sweetness comes up in mouthfuls of sour stomach bile from swallowing the anger and shame and a trickle of blood in my mouth from bitten cheeks.

II.

My mother smells of laundry detergent and an excessive, twenty-fabric-softener-sheet-per-load habit. There is the sting of cinnamon oil on wooden floors, bleach-coated bathroom tiles, and upholstery soaked in Febreze. When she approaches, she carries a sweet mixture of floral shampoo, hairspray, and baby powder. For all appearances, my mother’s home and body smell clean.

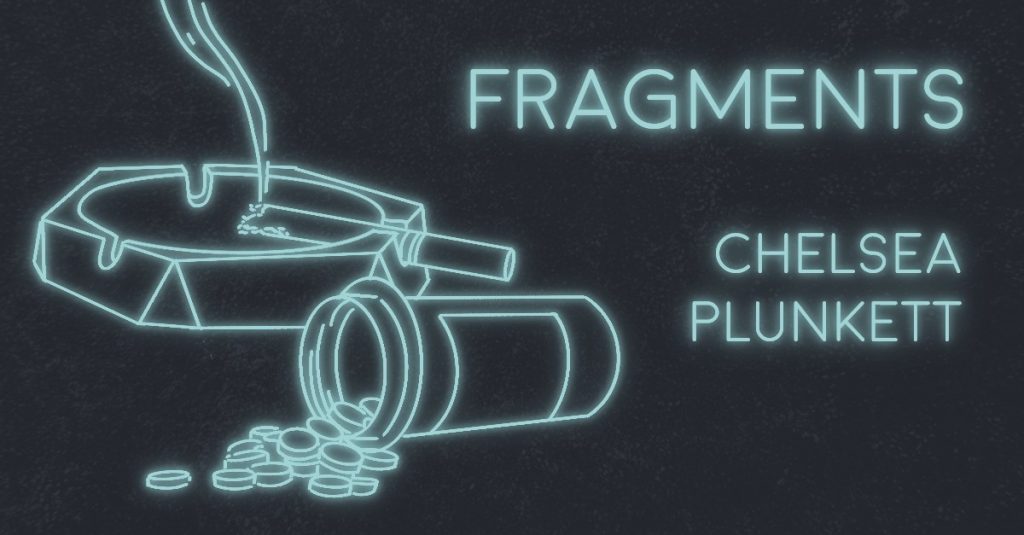

But within the house, she is the choking cloud of Virginia Slims that penetrates deep into the walls and furniture. It is a scent that spirals from her bedroom and mixes with our musty, flooded basement that sprouts mold up wooden paneling. Within her beat-up Buick, which has crashed into a mailbox, a sidewalk, and a ditch outside my elementary school, is the haze of blueberry air freshener and coffee. Outside, within my father’s old grill, is the scent of lighter fluid and burnt plastic from the wedding album she torched.

III.

My mother’s soundtrack is the rattle and pop of prescription bottles, of Fioricet and Clonazapam, of medication meant for my epileptic dog and a dead neighbor. It is her dragging, sweeping gait down hallways, a crash as she throws herself down the stairs and sprains an ankle, and the leaden stomps upstairs to my bedroom. It is fists slammed against walls, splintering wood, slaps and stumbles and screaming, always screaming, barbed insults hurled against my father, against my sister, against myself.

There is the cycling of Queen’s greatest hits as we bake Christmas cookies, the collected works of the Beatles in the car, and the cadence of our voices as we sing along to SuperTramp’s “The Logical Song.” Later, it is always the same songs—Alanis Morissette’s “You Oughta Know,” her anthem for broken marriage vows—muffled by the floorboards in my bedroom and the rasp of Janis Joplin’s “Me & Bobby McGee” in an abandoned Kohl’s parking lot, the orange glow of the radio as she hits repeat over and over, interlaced with accusations of betrayal as I break the news of my father’s remarriage. There is the thud of her body against the ground, her back arched over a humidifier, neck wedged against the nightstand, and a feral cry of “Mommy,” escaping my twelve-year-old lips in the night.

IV.

My mother feels like gentle hugs, a trace of fingertips against my cheek, the warmth of blankets tucked beneath my chin, and the contour of her hip and chest as I lie beside her in the flickering light of the television. In these moments, she feels safe.

But later, as she cycles to the end of a prescription bottle, her touch grows violent. It is the cool storm door against my palms as she points a steak knife, the vibration of hurled valuables and slammed kitchen cabinets, the weight of a prepacked go-bag shoved beneath my bed and clothing hurriedly stuffed in trash bags. There is the unbearable heaviness as I try to cover her nakedness before the paramedics arrive and my own anxiety-ridden fingernails digging at my scalp and ripping hair.

Even now, twenty years later and 500 miles away, I feel her touch, reaching through the phone to produce guilt and shame. There is dizziness, shaking, shortness of breath, and the rough carpet fibers against my cheek as I sob on the floor. It is the cramp in my wrist as I write in a journal she can’t hurt you anymore.

V.

My mind’s eye is misleading, as the portrait of my mother shifts and blurs with distance and time. The child within sees the possession, the complete and utter takeover that shifts her from parent to animal. It is her shadow self, pin-prick pupils and drooping eyes, clad in a wrinkled, ripped, and bleach-stained T-shirt and panties, towering over me as I crouch on the floor. It is her silhouette behind the wheel of a barreling sedan as my sister runs through the bushes, and a stare void of emotion as we face her in court.

There is the memory, a decade later, of untangling a bird from fishing line by the ocean, her features soft, cheeks flushed, eyes warm as we watch it stumble into the surf at dusk. It is seeing her eyes alight each time I come to town, and the devastating reminder of her humanity when we meet on video chat from the new lines etched around her mouth and eyes.

And lately, with her renewed instability at the forefront of my mind, it is seeing the lines form in my own face, deep frowns as I watch myself in the mirror while holding the phone. It is a technique to ward off panic, to render the memories of her shadow self powerless. But as I meet my own gaze, I cannot help but see her likeness. It is present in the line of my jaw, the shape of cheeks and brow bone, my thin, straight hair. She always said we looked like twins. And beneath the skin, peeking from my tired eyes, is the ever-present fear that this cycle could begin again.