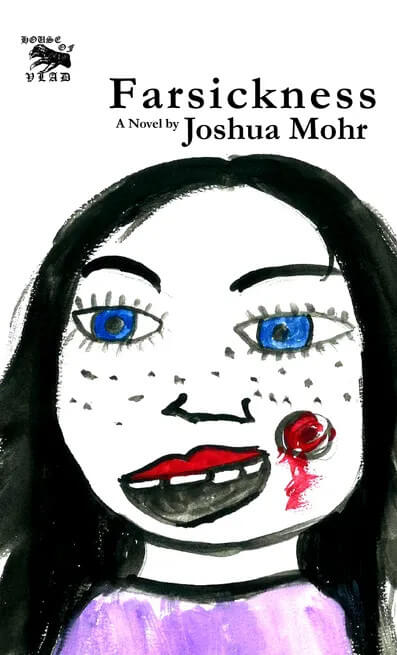

Coming to terms with the past entails the taking of many steps. Joshua Mohr’s peripatetic exercise in psychedelia, Farsickness (House of Vlad Press, 2023), embraces lostness and travels an uncertain road. Always in search of a steady place to land on shifting sands, the novel proceeds at an hallucinatory register. Out of Afghanistan comes a wounded legacy, where figments of a damaged imagination lead all the way to Scotland. Mohr employs the fantastic to journey into the harshest realms of the human heart, and then tries to make it back again. I spoke to Joshua about what the hell it all means.

Coming to terms with the past entails the taking of many steps. Joshua Mohr’s peripatetic exercise in psychedelia, Farsickness (House of Vlad Press, 2023), embraces lostness and travels an uncertain road. Always in search of a steady place to land on shifting sands, the novel proceeds at an hallucinatory register. Out of Afghanistan comes a wounded legacy, where figments of a damaged imagination lead all the way to Scotland. Mohr employs the fantastic to journey into the harshest realms of the human heart, and then tries to make it back again. I spoke to Joshua about what the hell it all means.

Rebecca Gransden: FERNWEH IS “FARSICKNESS,” A LONGING FOR A PLACE YOU’VE NEVER BEEN. The book opens with this statement. What is “farsickness” and why did you choose this term for the title of the novella?

Joshua Mohr: The project grew from a hunger, a craving, to escape. Covid lockdown nearly killed me. I went in barely sane, and a lot of me broke during that incarceration. So I cooked up a new world, a place where I could go. A place where I could feel impossibly seen and where anything is possible. I was homesick for adventure, and since I couldn’t take one literally, I turned my imagination into an Airbnb and hit the road.

RG: When did the idea for the book first strike you, and how long did it take to write?

JM: I wrote this novella very fast—did the first draft in three weeks. I then gave it to a couple trusted nerds, who gave me notes, and I did one remix based on those observations. I didn’t revise this story that much, truthfully, as it’s such a peculiar animal. It knows what it is. I wrote the story to read like Demented Whimsy, which was my North Star as I wrote. Keep the action deranged. Keep it joyful and whimsical. Blow up the reader’s brain.

Most of my books live in that kiss between the real and the impossible. Surrealism is one of my favorite toys to play with, and Farsickness was perfect for that. The story is so batshit right from the rip. This is the sort of story that people will either love or hate. Not much middle ground. But that’s how I like my art: emotionally volatile, harrowing, beautiful, nuanced.

RG: At the beginning of the novella, Hal’s memory is malfunctioning, and he is unsure of his name or history. He heads to Scotland by plane, driven by an irrational impulse that the place somehow means something to him, and is pulling him to it. Memory and what that means for us is a central theme of the book. What does memory mean to you and how do you explore it in Farsickness?

JM: My last book was a memoir, Model Citizen (FSG 2020), and even when I work in creative nonfiction modes, surrealism is never far from my artistic heart. In the memoir, I talk to dogs, cars, duffel bags, dead doctors, drinks, etc.—and that’s a true story! The human memory is so fallible, so faulty, so biased—and I wanted to honor those wirings by stripping Hal’s capacity to remember himself. He has to face certain past traumas in the book before he’ll be able to understand who he is.

JM: My last book was a memoir, Model Citizen (FSG 2020), and even when I work in creative nonfiction modes, surrealism is never far from my artistic heart. In the memoir, I talk to dogs, cars, duffel bags, dead doctors, drinks, etc.—and that’s a true story! The human memory is so fallible, so faulty, so biased—and I wanted to honor those wirings by stripping Hal’s capacity to remember himself. He has to face certain past traumas in the book before he’ll be able to understand who he is.

At its essence, this story is about existential amnesia. What do we need to remember? What do we want to remember? And what’s the difference between them?

I’m not that interested in realism these days, either as a writer or a reader. I want stories that smash status quos. I want to tell the big tales that live in my big heart.

RG: What type of research did you undertake for the book? You deal with some heavy issues, such as conflict, trauma, and PTSD. Did the process of writing the novella deepen your understanding of the themes you address?

JM: I didn’t do any official research. Most of my books, stories, scripts come from a characterization-stew made of the people I know. Hal is our avatar. We’ve all gone through a collective trauma with Covid, and we really don’t talk about it. We’re all siloed in our versions of some postmodern Roaring Twenties. I wish we were more honest with one another about our suffering. I wish we had that ability to really gaze into angst, and not dim it with an Instagram filter. I like my beauty unvarnished, un-airbrushed, warts and all. It is very confusing being alive, and my books write toward that confusion. I’m a mess. I bet most people reading this are messes, too. And I love that about us. I love that we’re trying to find our way home.

RG: You employ a classic storytelling style for the novella. At some points I was reminded of the darkness of the best of children’s fiction, such as Roald Dahl. This approach implies a reversion to childhood for your central character, where a simplified utilization of narrative becomes a way to examine difficult psychological and emotional scars. When thinking about style, was your conception for the novel one with clear intent or something that evolved more naturally?

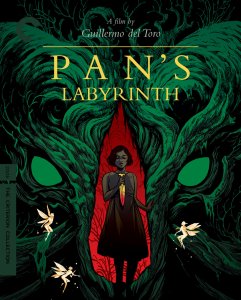

JM: The tone is very intentional. I love Guillermo del Toro’s film Pan’s Labyrinth, and that, too, is about using the fantastical to escape a present that causes emotional duress. To go back to my Covid Crazies—patent pending—LOL—I lost what little appetite I had to write realism. It doesn’t feel Real, at least not to me. Realism feels too clean, if that makes any sense, too explainable—and Farsickness is an arcane puzzle, much like our world feels like a warped end-times puzzle. But if I’ve done my job right, it’s readable as hell. The book is funny and fast. I paced it to be like a picaresque thriller, and it’s so short that I’m getting a ton of emails that people are reading it in one sitting, which is exactly what I was hoping for.

JM: The tone is very intentional. I love Guillermo del Toro’s film Pan’s Labyrinth, and that, too, is about using the fantastical to escape a present that causes emotional duress. To go back to my Covid Crazies—patent pending—LOL—I lost what little appetite I had to write realism. It doesn’t feel Real, at least not to me. Realism feels too clean, if that makes any sense, too explainable—and Farsickness is an arcane puzzle, much like our world feels like a warped end-times puzzle. But if I’ve done my job right, it’s readable as hell. The book is funny and fast. I paced it to be like a picaresque thriller, and it’s so short that I’m getting a ton of emails that people are reading it in one sitting, which is exactly what I was hoping for.

RG: Many of the characters encountered in the book appear as unlikely guides for Hal, and the novella visits visionary landscapes. At points, the narrative takes on the quality of a dream, and Hal frequently has stark choices to make. Is there a spiritual aspect to Farsickness, either for you in relation to the book, or embedded in the narrative overall?

JM: There are two main routes to interpret the action in the story: one is that Hal absolutely goes to Scotland, to the castle, and goes on a madcap adventure to save himself from the Army of Other Hals (with those unlikely and mostly un-human guides). And yet—again, if I’ve done my job right as the author—I’m hoping half the readers don’t think Hal went anywhere at all, not geographically, and that the entire book takes place in the haunted castle he calls a brain. We’re all these walking ghost stories, and I wanted to honor that spiritual truth.

RG: “Dil leads me through the sub. The MC Escher maze of corridors and chambers is disorienting. We spin open hatches and march the metal ladders. This is an easy world to get turned around in.” MC Escher is mentioned repeated times in the book. Imagery featuring mazes and doorways recurs. Can you expand on this?

JM: Great catch with all the Escher-osity! Hal’s job in the military was to clear caves in Afghanistan. So he did a lot of fighting in the dark. That kind of cave is a maze, one with real monsters, and so I set most of his trajectory in one maze or another in the story, some quite literal, some metaphorical. The book starts with Hal in the dark, and by the end, he’s found the light, in the only way that he knows how: by going to war with his own memories, his own traumas, his own flagrant trespasses, maybe, just maybe, that can lead him to happiness, to peace.

RG: “I can’t see where we’re going. The waters are too rough.

I follow the rope.

I follow Dil and Queen.

I have a son.

I have a voice in my head.

I have a rope in my hand.

This sub is sinking.

There is a castle that needs me.”

Hal’s inner monologue often breaks down to the barest essence, reducing his thinking process to its simplest components. I interpreted this to be an attempt by Hal at rebuilding a sense of self, a way to be in the world. Did you set out to use language as a way to demonstrate the psychological state of your characters, or was this a more unconscious factor?

JM: I really dig that interpretation. Thanks for telling me that. Yes, for Hal, he’s stripped mentally. If he was a tree, there wouldn’t be one leaf. So that required me to really pare the language down too, so that it can modify the cadences in Hal’s head. There are no Fancy Asshole words in this novella. This story would get stomped at Scrabble. A lot of simple sentence structures told in simple language. Now, that “simplicity” acts as the narrative’s foundation and because it is so solidly constructed as Simple, that empowers the surrealism. I can do all those nimble high-wire acts in the book’s batshit imagery precisely because the atomic particles on the line level are so controlled.

RG: Farsickness is to be published at House of Vlad Press. How did that come about? Any thoughts on the press in general?

RG: Farsickness is to be published at House of Vlad Press. How did that come about? Any thoughts on the press in general?

JM: I loved working with Vlad. The cat who runs the press, Brian, is a hell of a writer, and we had good times bringing this story to life. We should all be supporting the indies. That’s where the exciting art is happening anyway. Mainstream publishing—and this isn’t sour grapes, I did my last book with FSG—but mainstream houses right now are publishing a lot of bullshit. A lot of defanged art. A lot of remixes of remixes of remixes, its own pandemic. I call that conveyor belt bullshit Beige Against the Machine. The indies! That’s where the really thrilling stories are being told.

RG: The book features illustrations by Ava Mohr. How did Ava become involved?

JM: Ava is my nine-year-old daughter! Collaborating with her is the main reason I wanted to do this little book. We had a blast, and it wasn’t a one-way collaboration. Some of her watercolors were so amazing that I revised my character descriptions based on the images. We already have another idea for something else to do together. Making art with her was arguably the highlight of my entire career. Her imagination elevated the art.

RG: In many ways the novella is an odyssey, with critical meetings taking place along the journey, and characters that inhabit the role of facilitators in the story. In the end, what does it all mean?

JM: How do I know?! LOL. The story stops being mine once it’s bound and placed on the shelf. I believe that my books are hibernating, until a reader is generous enough to bring the story to life in her mind’s eye. Then it’s hers. And I want to make her feel! I want to empower my audience to build their own cities of interpretation. Farsickness isn’t the kind of art that invites consensus. I want a bunch of varying reads. Where is the fun in consensus?

JM: How do I know?! LOL. The story stops being mine once it’s bound and placed on the shelf. I believe that my books are hibernating, until a reader is generous enough to bring the story to life in her mind’s eye. Then it’s hers. And I want to make her feel! I want to empower my audience to build their own cities of interpretation. Farsickness isn’t the kind of art that invites consensus. I want a bunch of varying reads. Where is the fun in consensus?

I like to imagine a kind of intimacy with my reader that it feels, to her, that when she’s reading the story, I’m plopped on the barstool next to her, whispering right in her ear. This story is just for us. The two of us. Co-conspirators. I wrote it only for her. I wrote it only for YOU.