Elbows smashed against a stranger like in a metro car going the wrong way. I stub my cigarette in a dirty plate and pull my dress over my head. Green and brown geometric shapes flare. I force myself to face the painter. I pull down my underwear. Reach to unhook my bra.

—Leave that.

The painter grabs a glass for me, rubs the rim with his shirt, and fills it with wine. His smell reminds me of the time I took a swig of apple juice only to find that it was bacon lard.

—Je suis un exilé, he says.

—What kind?

—Czech.

—Have you ever gone back?

—No…Better to know the snake in front than the one at your back.

—I hate Paris too.

I sit on a stool. Gaze into the large gilt mirror. Empty bottles on the windowsill. Dusty books on the floor.

—It’s perfectly safe here. I am an old man. Do you have a boyfriend? No boyfriend problems.

I nod. He fondles a piece of charcoal and looks at me before touching the paper. The line makes a limp imitation of a spine. A nose appears. He groans.

—What I make is so far from what’s in my head.

He lifts a box of chocolate cookies from behind his easel. Drops one in his red wine. Waits for it to melt. Pieces of cookie sink and rise in the glass so that when he takes a long sip he also chews. He must be dying. He must be dying but it will take a long time.

—Take one.

I take a cookie. It’s dry. And this childish thought: Does the girl have to finish the cookie before she can leave?

—You make me think, tu sais, of Nadja, the muse, he says. Do you know that book?

—Yes.

—Who wrote it?

—André Breton.

—That wasn’t a test. I have something to show you.

He grabs a large portfolio. Tries to frown but his teeth show. His sketches are ochre, red, dragon green. Knees bend like branches. A vagina is a forest, a red-streaked cave.

—What are those stains?

—Oh anything. Sperm or coffee or shit…blood, wine.

—Exile is difficult, I say.

He puts a birdcage veil on my hair. I touch it. It’s filled with pearls. He tells me to kneel. His fingers take my face, adjust its angle. I lean into his palm, lick it. Then, an instinct. I bite until I break skin. It’s the hand he paints with. He doesn’t try to stop me. I release him only when the taste of gunmetal fills my mouth. The painter rubs the bleeding hand across my face and stands beside me. We watch our tableau in the mirror. I smile. Blood on my teeth.

—I am going to take a photo with my mind, he says.

I pull my dress on and wash my face in the sink with a square of ivory soap. He slashes a canvas in a fever.

—Is this for me?

—Take it.

I take the long way home, skirting the canal, and count and separate the money: half for Maman, half for me. Wander into Sympa and dig through the bargain bins. Leave with a polyester dress. Outside, men race motorbikes in the growing shadows. Mirror glass shines in the street. I watch litter lap the edges of the canal. The water shimmers green and gold. I turn down a side street. Skinned rabbits watch me from the butcher shop. Shame crawls in front of me. I step around a child drawing flowers on the sidewalk. Throw the dress in the trash.

Home. I open the door to a shallow grave. There is the long wooden table with one broken chair. There is the red rug stretched like a tongue where the cat used to sleep. There is Maman on the floor.

—Maman?

…

— It’s my tooth.

—You need the doctor.

Her calves shine white under black nylon. Her hair lies blank, dumb, down her back.

—Non.

—Papa’s dead.

I can’t see her face.

—J’y vais pas.

I remember Papa’s rules: give Maman herbs instead of lithium, stitch my sliced hand on the counter. I’m seventeen now. It’ll never be his household again.

—Then suck on a clove.

—I have four in my mouth; I’ve taken all the aspirin in the house.

Maman can’t sit still or lie down by midnight. Upstairs, two children cry, muffled and desperate.

—Maybe that boy is watching a pornographic movie? Maman says.

No. The bed board knocking, the springs creaking. A man’s low growl. A woman’s happy sob.

—Bon, no longer puceau. With his face, I’m glad for it. She almost laughs. I bet they’ll have a baby.

When she talks blood dribbles on her lips. I wrap ice in a washcloth. Maman holds it to her jaw.

—Will you pull it out?

—Don’t be crazy.

—Please.…The pressure will go away once it’s out.

—No.

—Please.

—I don’t think I can.

—Please.

—Sometimes I want to hit you.

—This will hurt more.

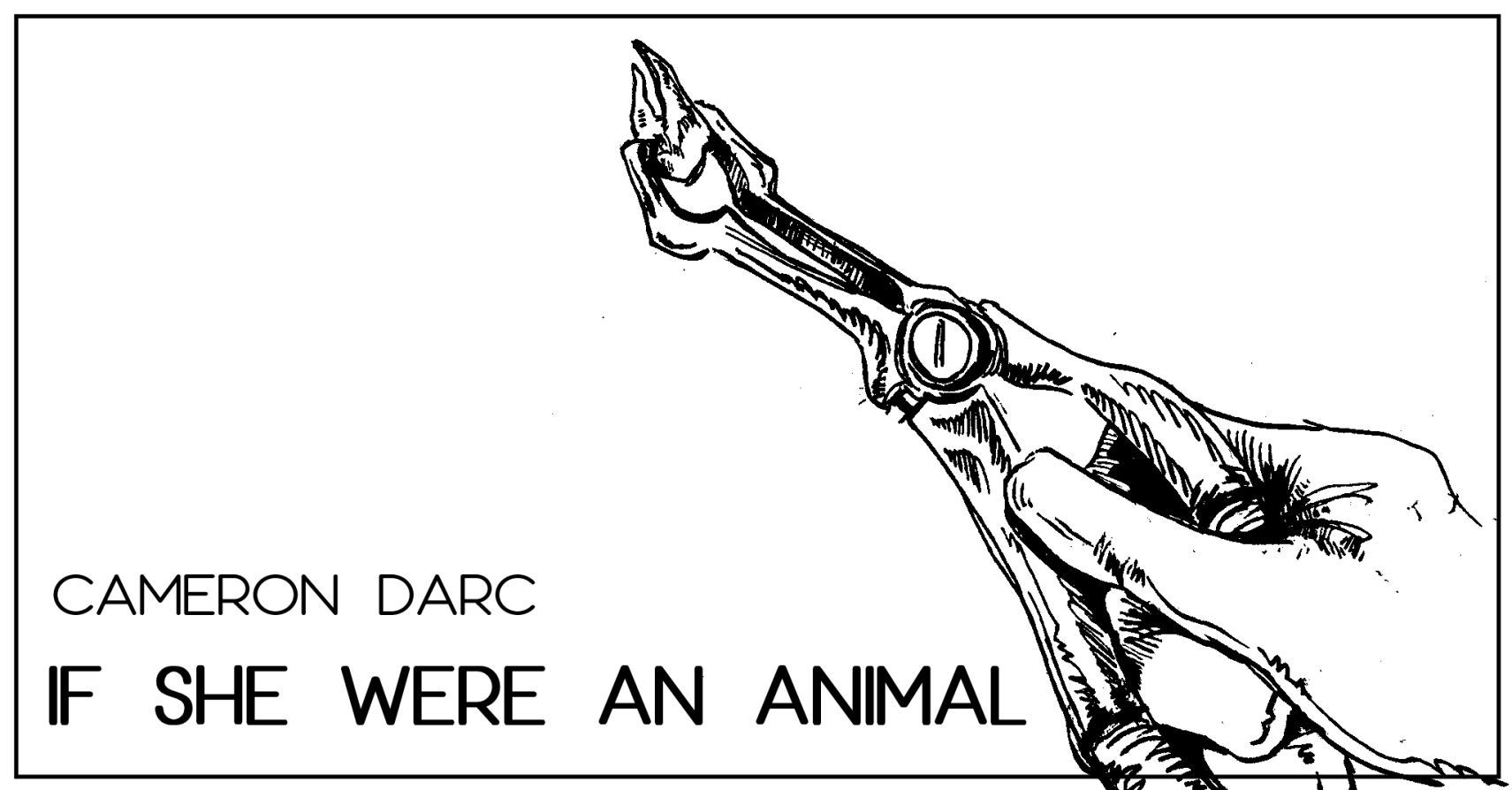

—Do we have pliers? What do you suppose I use?

—Fingers.

I follow her to the bathroom, pull the chain on the light. We were adjusted to the dark and now our eyes flicker. Her face is too sober.

—Maman?

—Don’t worry.

—Drink something first.

—I’m sorry about your cat. I still feel him—he’s somewhere around, you know. Maybe a neighbor started feeding him.

—Don’t talk.

—When you do it, pull hard, harder than you have ever pulled a weed out of the ground.

I bring her the whiskey. She pours some in her mouth, then swishes it around. I wash my hands well, even under my fingernails. Maman pulls her shirt off. Sits on the toilet seat, waiting.

—I’ll take my time, I say.

My fingers shake.

—Take a drink.

I hit my front teeth on the bottle. Swallow as much as I can without puking.

—Don’t be afraid to hurt me.

—I’m not.

I come close enough to kiss her. Little blood stars spider on her cheeks. Dots of blue all around her eyes. Her breath stinks like someone with a fever.

—It’s tender, I whisper.

My pointer grazes the sharp scrape of tooth. Maman flinches in reflex, would twitch her tail if she had one. Shows me her teeth, the flash of a killer in her eyes. Comes back to herself. Sucks in her stomach with the cesarean scar and folds her hands over the pendulous breasts that will be mine someday.

—Sorry. I won’t move again.

—I think that red is an abscess.

—The gums want it gone.

—Hush. Drink.

She takes five deep swallows. She’ll be sick after this.

—I’m ready.

—Wait.

—It’s like an abortion.

—Shh. Go someplace nice.

Her eyes lock on my face.

—My daughter.

I put my thumb on one side and my finger on the other and wiggle.

—It’s not so solid.

I dig around the base, pull. I see the roots. Blood rivers between Maman’s breasts, pools in her white underwear.

—Keep going. Don’t make me do it myself.

I squint my eyes and yank. Maman doesn’t cry out. I show her the tooth with its long tail. Put it in the soap dish. I make her swish her mouth again with the whisky. Then the peroxide. She spits, brown, red, all in the sink. She tries to stand, holds the mirror, vomits on the tile. I bring her to the shower. Hose her down. Her hands slip down the wall. She hits her head. An egg on her tomorrow. She cries but her eyes are empty.

—I don’t want to live.

She has the voice of a stranger, slurring through water.

—You’re drunk.

—But it’s true. I want to die.

I fill her mouth with the cotton gauze she uses to remove her makeup. Bring her to the sofa. Her body is soft when it’s wet and naked. Lie on the old air mattress on the floor beside her. Listen to her breathe. Make sure she doesn’t stop.