Jesse Hilson recommends…David Kuhnlein

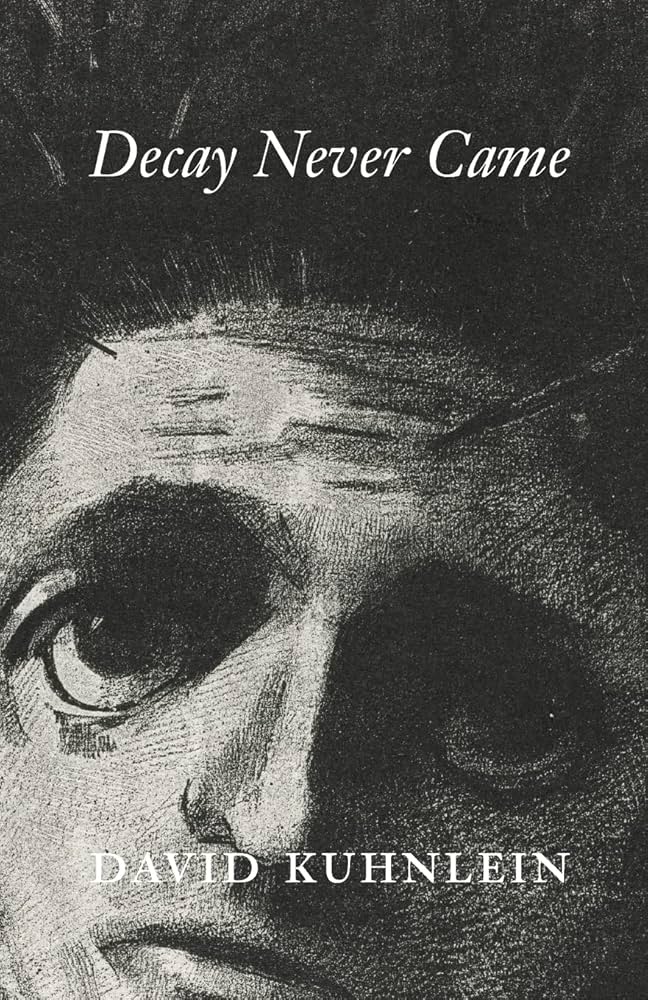

Decay Never Came (Maximus Books, 2023)

Decay Never Came (Maximus Books, 2023)

The text of this chapbook is less than forty pages long but it can’t be read in a hurry. It can’t be gobbled up like a small package of black licorice. Slow down and take in each line one by one. You are now reading at the slowest setting of the necro-metronome. The book’s title is Decay Never Came, suggesting that a jump into a different, longer timescale is required to get what the poems are doing, with the risk that even then this could not be possible. A strong atmosphere of aesthetic death exists throughout the collection: the beauty in death, or maybe more accurately, the beauty of a body’s biological trajectory plus inevitable time. “Herniated before I was biology, in decay that never came,” Kuhnlein writes in the titular poem. And maybe it didn’t come, but was perhaps expected to, since we have passed into the empirical envelope of death. Bodies, in Kuhnlein’s world, are sites for exhibiting value-neutral damage, illness, injury. In “Wooden Spoon,” the speaker of the poem likens bruises suffered in BDSM encounters to stars, saying “I’d let you whack an entire history of / hot white stars // the galaxies in me! & isn’t it funny / how pleasure w/in pain / & not the other way around surrounds / me // w/ pieces of the everyday”

In “Bloodborne” we seem to eavesdrop on a corpse asking “is this a body bag or a river I’m in”:

My fingerprints dehisce their perimeter

Like psychotropics darting through blood

Red ants bite me in swells of cursive

Relatives’ prayers teem, gleaning as they flay

I’m stuffed into a burlap sack…

The weak taxidermy of my surname thaws

Ashes melt up my knuckles without me

A morbid tone pervades the collection, which is nothing new, but what tends toward the original about Kuhnlein’s writing is the spectacular variety of phraseology about bodies in extremity, the chorus of voices singing about rot, abuse, or even just some other living morphology. Several poems describe sea lifeforms with a fascination that is not as gothic as the rest of the productions might be (to resort to idiotic shorthand: “gothic” is a term prone to some of the worst misprision and I apologize for using it here—and yet Kuhnlein is unquestionably macabre). Starfish, sand dollars, and seahorses have dreams shaped by anatomy known to science but alien to human creatures. “Pacific townsfolk crave my cross-shaped uteri,” the sand dollar apostrophizes. It isn’t clear whether the speaker in “Starfish” is a starfish or is addressing a starfish, but some form of relationship is being referenced:

My bag of blotted capillaries eversible inside my oral disk

I scarf your milk teeth, suction cup shoes, and pillowcase tongues

My weeping thirst carves a singular grave

For us in this ruin of beach sans melody

As the cackling sun crisps your tendons to mine, alphabetically

Kuhnlein’s vocab choices have just enough clarity to make meaningful reference to his subjects but just enough reverb to put you under a cloak. A somnolent gel floods all spaces, like that seen in the surreal cover photography for old 4AD records or Brothers Quay animations. You’re having a nightmare but it’s hypnotizing in its beauty, and the really bad part hasn’t happened yet. It’s an atmospheric buildup.

Kuhnlein recently wrote a short zine’s worth of film reviews, horror movies, called Six Six Six, and his facility for coming up with fresh, engaging language was as much on display there as it is here. But the poetry is perhaps hazier because the goals are more abstract than “communicating to you about some more or less fixed popular culture.” Writing that can swerve into the territory of spooky phantasmagoria and still come back out as original is not so easy to come by. Decay Never Came does manage to have the lineaments of that. My main criticism of the collection is that it might have had too much the lifespan of a gentle moth as opposed to some organism that was more robust and sustained over time. Chapbooks are like micro-ghosts trying to scare up a living room, when what Kuhnlein needs is to unleash a poltergeist, something destructive that breaks doors, shatters mirrors, melts fireplaces, inspires more elemental fears.

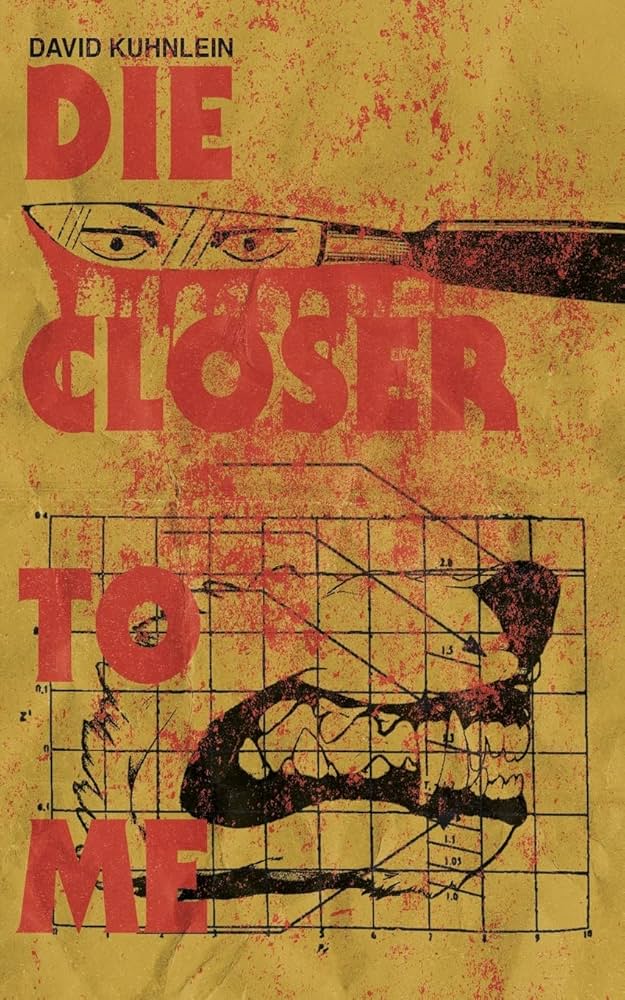

Die Closer to Me (Merigold Independent, 2023)

Die Closer to Me (Merigold Independent, 2023)

Die Closer To Me is a slim novella but a considerably large jigsaw puzzle that needs to be reread in greater detail in order to see where the pieces interlock. A novella-in-stories, as the back cover reads, the book is a literary sci-fi tale comprised of thirteen short stories that have tantalizing overlaps. Blink and you might miss the slivers of the Venn diagrams where one story interfaces with another. This is not to suggest this is a design flaw; rather, it is a spring-loaded mechanism which unleashes its potential energy and sends the reader back to the beginning of the book to put it all back together again.

Plot-wise, it’s a little unclear — chopped into chunks as it is — but the central mass of the story seems to concern another planet named Süskind, which has existed unseen in our solar system and become a vast experimental home base for people with disabilities. Indeed, medical ailments and their treatments form the background scrim against which the story is told. Or untold. Narrative canvases are painted and arranged into triptychs or tetraptychs (?) that may not be delivered in sequential order, like an artwork not meant to be taken in a linear fashion. The stories allude to one another through revealed names, bags of drugs, Buddhist texts, hyper-developed senses of smell, photographs, motorized wheelchairs, and other incidental details and clues with interrelated matrices that don’t vex the reader (at least they did not vex me) but give a pleasurable teasing sensation. It’s a book to be reread and taken apart and fitted back together for fun.

The prose style of the book should be mentioned, as on first reading (there will be more than one) it upstages everything else, including plot and character. Not that those are lacking. Kuhnlein has shown himself to be a poet and skilled weaver of lyrical, surprising linguistic units. Much care has been put into crafting paragraphs, such as this description of an Earth-bound psyop to re-scramble domesticated dogs for nefarious purposes (it has to do with Süskind, I promise):

“Spontaneity is regarded with suspicion. The result of a universal love based on abstract principles is meaningless since any extreme contains its opposite. Too much love becomes hate. Project House Dog didn’t anticipate that dogs would become cognizant of what they’d lost, or what might happen when they did. After a while, eunuchs thank those who sever them from time-consuming and pointless arousal. Imagine the potency of a reverse orgasm spilling backwards against the sense organs, bittersweetness increasing by the bite. Lying with a proper muse can rebuild an inner banquet in minutes. By way of encrypted audio files hidden in DOG TV videos on YouTube, dogs were reprogrammed with their original fertility and virility, as well as their predatory instincts. These dog-friendly messages slipped under the radar, unheard by human ears, spraying across a sky of satellites, scrambling themselves into domesticated tissue.”

Dogs activated by YouTube videos as if Manchurian candidates or sentient masks in Halloween III: Season of the Witch are just some of the fiendish creations in Kuhnlein’s novel. Homicidal bounty hunters, psychopathic anesthesiologists aboard interplanetary spacecraft making jaunts to the disability planet, dangerous insects, Buddhist cults — all are found there, yet they seem to transcend genre fetters as we might imagine them and are instead written about with delicacy and inner penetration. The literary/genre divide is straddled and, in many instances, smashed as thoroughly as a marble bust by an iconoclast, if only to have the pieces reconfigured into some new pattern that retains allusive hints of the old: it is sci-fi, with the trappings and atmospherics, but the speculation and imagination are taken in fresh directions.

It’s dark, it’s cyberpunk, it’s as fleshy as Cronenberg’s most outlandish charcuterie board. It’s alive, it’s menacing, but, in addition to that, it’s sensitive and human writing. It’s a spiritual act to go among these broken people and glitching relationships, and to reflect that in the distant future Buddhist concerns — the freeing of the material from disappointment and suffering — will still be on people’s lips. The natural order of things is probed, lanced, massaged, and bombarded with mutagens under Kuhnlein’s pen.

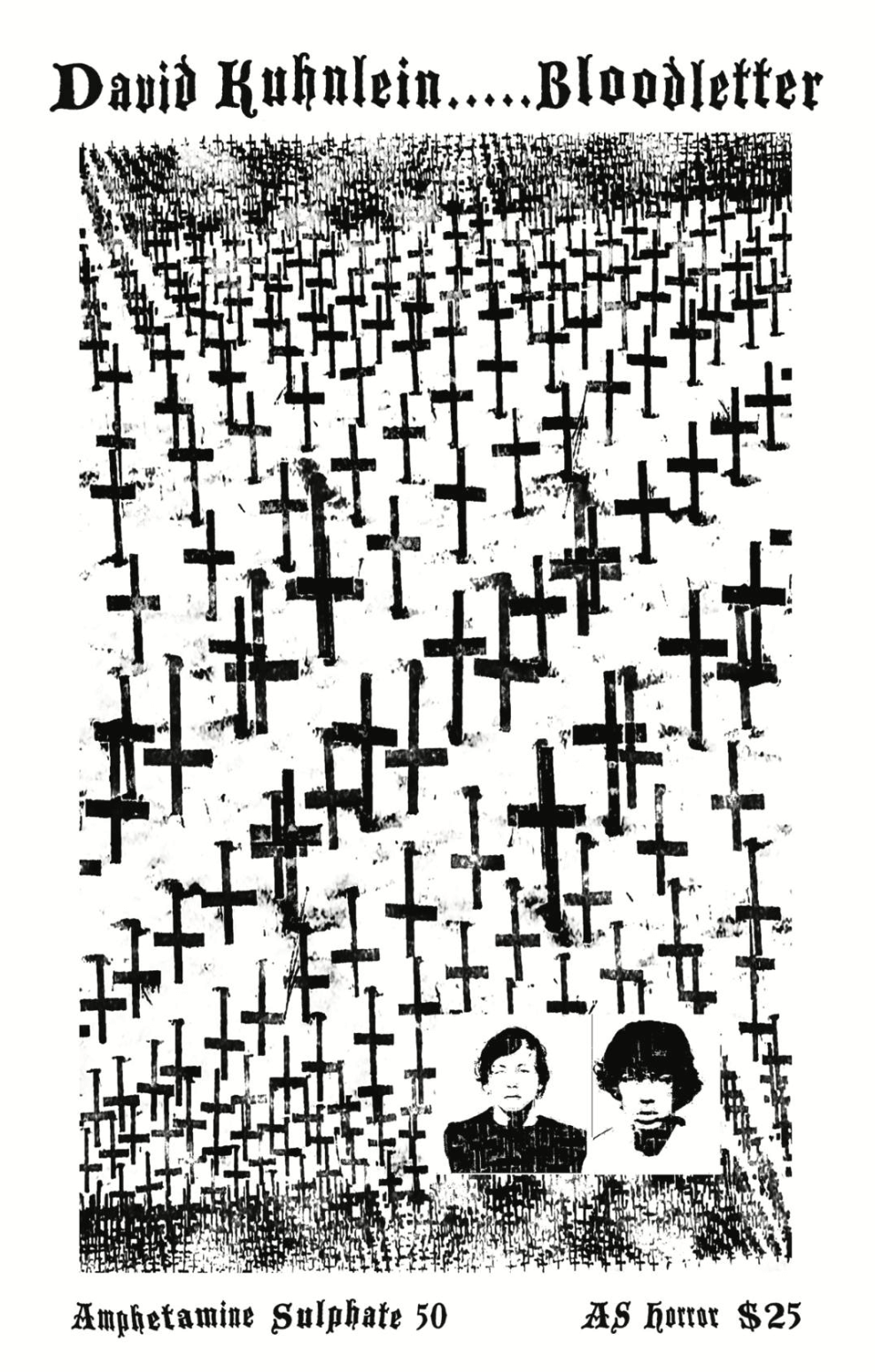

Bloodletter (Amphetamine Sulphate, 2024)

Bloodletter (Amphetamine Sulphate, 2024)

David Kuhnlein’s Bloodletter, at 112 pages, would be a quick read, if the brakes weren’t everywhere applied by the enigmatic, impressionist prose that requires extra consideration, damn near divination, on the part of the reader. Each carefully toned and balanced sentence could contain a shelf full of poetry volumes. A lot of people call themselves writers, but few can lay claim to the title of “prose stylist.” Kuhnlein easily fulfills those requirements in Bloodletter. The only question is: Is the reader ready to stomach two historical true crime novellas written at high pitch which feature some of the most ghastly descriptions of serial murder you’ve ever seen?

The novellas were undoubtedly based on a formidable amount of research on Kuhnlein’s part into; 1) the Narcosatanicos, which was a Santeria-practicing cult of homicidal drug smugglers in Mexico in the 1980s, and; 2) Bela Kiss, a prolific Hungarian serial killer in the early 20th century who fought in World War One and kept dead bodies in barrels. Maybe you didn’t understand when I said “formidable amount of research.” These narrators of Bloodletter are lived in, to the extent that you may as well be reading the transcriptions of their fevered, inward-most dreams filtered through a finely etched aesthetic prism.

Kuhnlein’s murders are not presented coldly and clinically, which would seem to be a preferred method in true crime when it indulges in its aspirations to journalism. In contrast, and happily from an artistic standpoint if not a moral one, he writes murder from a heated, lush, rococo perspective, full of nooks and crannies for the reader’s mind to catch on. It’s gorgeous but it’s so so evil.

“Downwards,” the first novella, takes place in Mexico, where “cops, lawyers, actors, border patrol, gang members, doctors — everyone pissed their soul away for protection.” A female member of the Narcosatanicos gives this description of the ritual preparations she goes through:

“At the end of the week, I break into a cemetery, carrying a set of clothes, exhume a criminal, and dress the corpse. During the next twenty-one days, I follow a rigid schedule of baths that consist of mint, basil, camphor, and other purifying herbs. I return to the cemetery, dig the corpse up again, and put the clothes back on. By the time I’m back at the ranch, I only smell death when the sleeve is placed against my nose. Tan splotches cover the rags, which feel breezily ethereal. The sky is lit by oil. Adolfo says spirits flood me, but I feel emptier than ever. I’m given a white candle on a dish, a human tibia, my scepter.”

Kuhnlein’s catalogs of ritual objects and ingredients — the macabre set design of the cult’s headquarters in Mexico strewn with dead body parts and dead animals — are described with evocative, wild squalor. “The federales who serve my warrant will puke up a squirrel,” cult leader Adolfo Constanzo foretells, out of narrative time-flow. “Once their eyes adjust to the dark, what they see within my walls will live inside them forever. No one who works this case will be long for the force.”

The second novella, “Backwards,” follows the killer Bela Kiss into World War One, where he hides in plain sight as a cannibalistic monster. The historical war scenes were the strongest part of the second half, I found on my first reread of Bloodletter. Bela Kiss recounts a foraging excursion:

“Raiding the pantry of a house on the outskirts, a dog finds us well, competing for victuals. We slice an ear off first. When it runs, yipping, another of us claims a paw, saber-spearing with accuracy…The ribs are stomped dislocated, exposed and everted, a wet integument of fur snipped to dry in the sun…Freedom fighters come to avenge their dog…We skewer their Belgian bellies, plop them on the spit out back.”

“Backwards” was perhaps more difficult to read, harder to track exactly what was occurring plot-wise. Kuhnlein’s fiction, I have learned, is not particularly meant to be read as pedestrian, suburbanite “stories,” with a narrative edge clearly coming across, but as sibylline recitations more akin to intoxicating prose poetry. It’s a high artistic accomplishment and seems to fit with publisher Amphetamine Sulphate’s coterie status as purveyors of refined, skin-crawling, cursed Sadean literature for the 21st century.