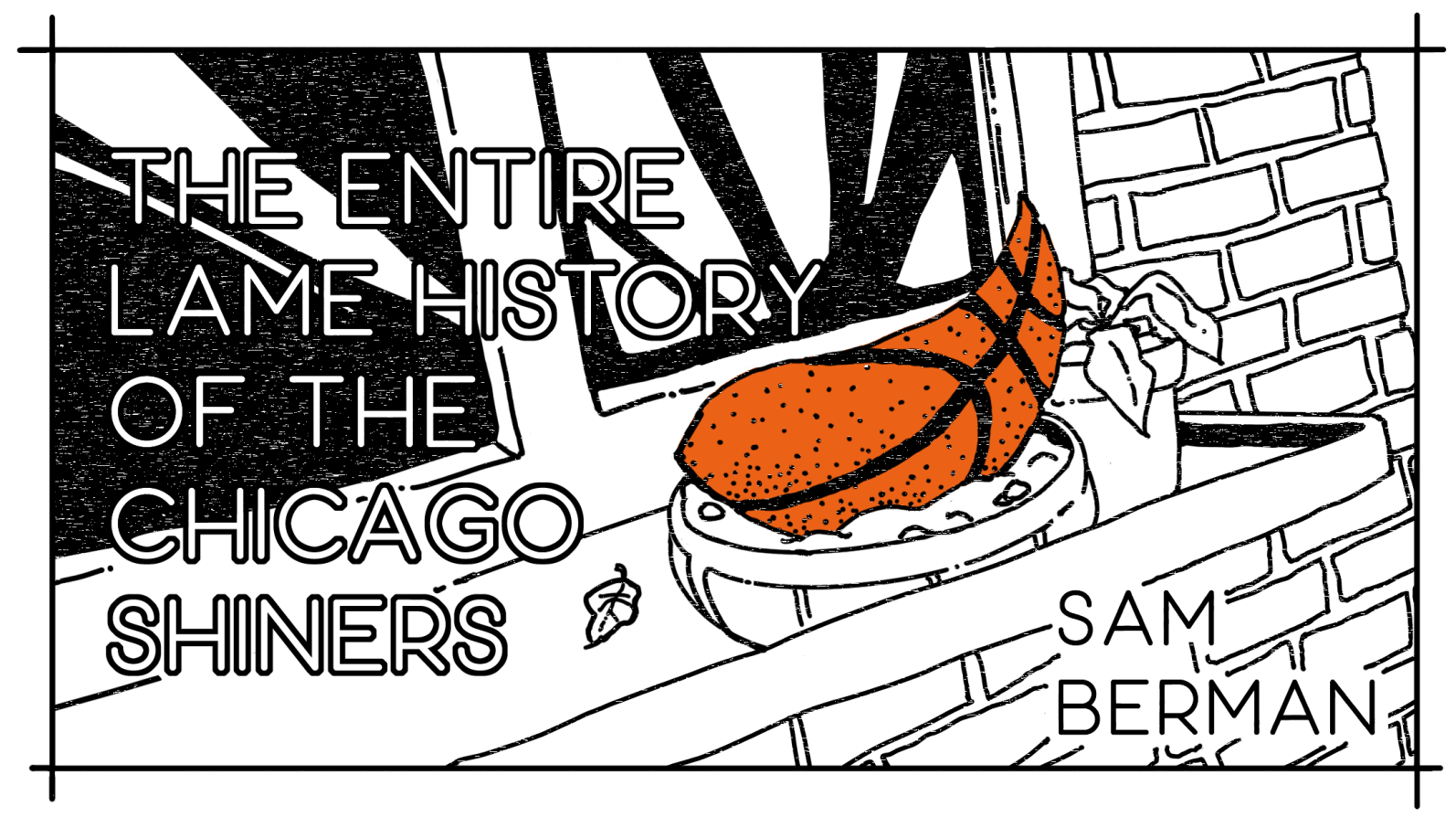

A slice of an orange basketball landed in the windowsill that popped off a ball from the street below. Or possibly fell from a Wilson Plane or Adidas’ Zeppelin.

Like a good little dumbass man, I planted the thing in a planter box next to some dead jasmine and dying clematis vines.

And. Would. You. Not. Know. It. I grew my very own NBA organization. Which was amazing and scary. And when it was scary, I worked for eighteen months getting all the extra wood and nails I could find in the city and the surrounding suburbs. Which is when I met some amazing dumbass men building a lot of really nice houses with big bay windows. Many of those contractors and roofers and electricians are now fans of my team. Some of them hang out in the VIP lounge and smoke orange cigars in the parking lot after games. Once I built the cool and funny wood stadium.

That’s when me and my wife got to work.

Now: I have ten sons and two daughters that play for the Chicago Shiners. And I coach us and am our General Manager. And my wife sews the uniforms when there are tears or when one of my sons––after a tough practice––wants to try changing his name. I’ll be honest, we don’t win very often. A team four years ago scored 270 points against us. An NBA record. I’ll be honest again: We’ve never won. And sometimes that gets really hard. Like hard. To lose and lose. Like so hard I wonder If I should give up the team I grew; just throw the keys to the stadium off the top of an overpass.

But then, at the end of last year, we lost to Dallas in overtime. And my sons were lying dead-tired, all flat, like starfish dumbass men across the court. It felt like a loss––certainly––but also a little like we’d done something real close to a not-loss. A movie ending type loss. A loss, but less. And when everyone got in their bunks that night, and we went over the plays––good and bad––everyone, even my pimply daughter, had thoughts on how we could get better.

“Kyrie’s an animal. Put Cassie and Kevin both on him next time,” said someone.

Then Cassie and Kevin got down from their bunks and started doing push-ups in the aisle even though they both had ice on their knees and shoulders in those nice ice bags their mother sewed on our vacation to Ireland. God, we all laughed at that. God, I realized then, it’s not so much about winning. But God, I kinda knew that when the bird farmers in seersucker suits told me they’d give me two-hundred thousand to paint their hatcheries’ names on the side of my cool, funny, wooden stadium.

And I jumped up and down, screaming, “Thank you, Lord! I need this money for the leaks! The Powerade machines! And the Nitrogen tanks for the t-shirt cannon! You boys got a deal! Woo! You got a deal!”

And then I fell to my knees while the farmers walked back to their black Suburbans—except the oldest and most southern of the bird farmers, who stayed behind a moment and came up to me while I was on my knees, telling me quietly with his hand on my shoulder, that, “It’s quite rude to pray with that kind of specificity.”

God. I can be a rude GM.

God. Nothing is about winning. God is more than a winning thing––more than a buck. God is every win we will never have as an organization. God shares my taller daughter’s name now.

Which is Hope. I say it five times when she covers the inbound. Hope. Hope. Hope. Hope. Hope.

Sewn in her mother’s cursive to the back of her jersey like a note to leave school for the eye doctor.

Except sometimes.

Except sometimes I call her, “Bope.”

Like: Bad Hope.

I do that.

When she misses her free throws.