In the cultural-zeitgeist-universe, Gwen E. Kirby’s writing occupies the same galaxy as Midsommar and girl dinners and Le Tigre and riot grrrls. Meaning: they are compatriots orbiting the same star — a fed-up, fucked up, frenetic, and funny amalgam of contemporary femme life.

In the cultural-zeitgeist-universe, Gwen E. Kirby’s writing occupies the same galaxy as Midsommar and girl dinners and Le Tigre and riot grrrls. Meaning: they are compatriots orbiting the same star — a fed-up, fucked up, frenetic, and funny amalgam of contemporary femme life.

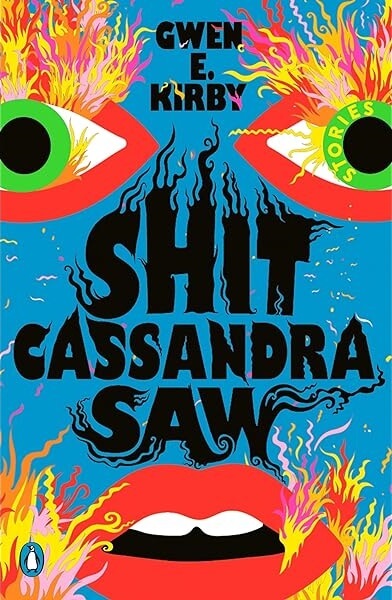

In Kirby’s case, the pull isn’t gravity, but the sharp, detailed humor she weaves into her fiction. Both Shit Cassandra Saw, her recent collection of short stories, and “Jackfruit,” published with us last September, showcase her talent for fusing the absurd and the true. Reading it, I was stunned by how the emotional resonance and wit remained constant. The length, breadth, and scope of the stories varied, but the depth never waned. Over email, Kirby and I spoke about how she packs those kind of punches in such small spaces.

Jessika Bouvier: Talk me through your mindset going into drafting. When you set out to write a story, do you always have length in mind? Like, ‘fuck yeah, it’s Tuesday, time to tackle a micro’, or do you find fiction-making comes easier when you let it emerge more organically?

Gwen E. Kirby: Ha, I don’t think I’ve ever entered a writing session thinking, “fuck yeah!” though I would like to cultivate that mindset! Sometimes I have a seed that I know I want to explore, a place I’ve been thinking about or a weird idea that has gotten stuck in my brain (“Jackfruit” is definitely an example of that second kind of story and a story that, due to its weird premise, I knew would be pretty short). But a lot of the time, my first drafts are the product of me sitting down and saying, “alright, time to attempt to write something!” and then I start typing and see what comes out. When it ends up working, it’s usually because I’ve captured a voice I like and want to stay with, see where it goes. Length isn’t typically something I pre-plan. Some stories have to be short to work, some have to be long, and sometimes you think a story will be a piece of flash fiction and then it’s ten pages and counting. I think the important thing with length is not to let your preconceived idea for the story (whether it be micro, flash, etc.) get in the way of what the story actually wants to be.

JB: We see tons of variation in Shit Cassandra Saw, which is part of what makes it such a fun read: the prose has so much levity on its own, but then you never really know what you’re in for when you hit the next title page. Do you find your relationship to a story changes based on the length and form it takes? Is intensity always dichotomized by concision?

GEK: This is a good question! At first, thinking it over, I thought no, I have the same relationship to all of my stories. They all surprise me (because the stories that don’t surprise me are in a folder on my desk, never to be seen) and they all challenge me to be a better writer because there’s always the best version of the story that I can imagine but never totally capture. But being more honest with myself, I do think I have a more emotional relationship with my longer stories because they take me longer to write. Flash is really hard to get right but also I can tell pretty quickly if a flash piece will never work and I need to move on or if it can work and I need to chip chip chip away at the words until what I want is distilled on the page. For stories that are long, I can work on them for years and still end up having to let them go because I can’t make them work. Sometimes I write and write and never see the forest for the trees. So when I finally get a longer story—“Casper” and “Here Preached His Last” come to mind because I struggled and wrestled with those!—to a place where I’m happy, I find myself emotionally attached to them. As for intensity, whether short or long, I want a story to have moments where you hold your breath and moments where you release a sigh. Intensity belongs in every story.

JB: How long did it take Cassandra to become Cassandra? Were you writing toward a collection while drafting these stories, or did the connective tissue reveal itself over time?

JB: How long did it take Cassandra to become Cassandra? Were you writing toward a collection while drafting these stories, or did the connective tissue reveal itself over time?

GEK: It took a long time! “The Disneyland of Mexico” was the first story I wrote that ended up in the book and “Marcy Breaks Up with Herself” was the last, with about eight years between the two. I didn’t think about creating a coherent collection for a lot of that time. I was much more concerned with figuring out what kind of story I wanted to write, how I might want to write it, and learning the tools to execute my ideas (a never-ending quest!). The thing that ended up bringing the book together, at least in my mind, was starting to write flash, first with the title story “Shit Cassandra Saw . . .” and then with subsequent flash pieces about women from history. It made me conceptualize the book as bringing these women together across time, with the historical and contemporary voices speaking to each other informally, sharing a table together with a nice drink and a snack. The historical stories in the collection are ordered chronologically and the final story of the collection ends in the future tense, which to me feels hopeful. In the end, I hope that my interests and my voice make the collection feel united but not repetitive, but that is for my readers to say!

JB: Digging more into content, you’ve spoken in the past about how your writing centers “complicated women” in historical and modern contexts, something that definitely pulls focus in “Jackfruit” and throughout Cassandra. Finishing the collection, the depictions of girlhood in “Mt. Adams at Mar Vista” and “Casper” (a personal favorite) really stuck with me, made me think about how we talk and think about “complicated women” before they really become women, whatever that means. I’m curious how front of mind this tether is for you; are you thinking about the pipeline from girlhood to complicated womanhood when writing these younger characters? Do you see these as fictional “origin stories” of sorts?

GEK: I definitely think about those stories as existing on the same continuum because really, how can they not? In both “Mt. Adams at Mar Vista” and “Casper,” I am really interested in girls’ friendships and in how girls act in groups (same as the teenage girls in “We Handle It,” which is in the first person plural “we” point of view). I have never thought about it before this question (so thank you!) but I think that my older characters tend to be more isolated than my younger characters and I actually am pretty intentional about trying to add in at least one friend for my adult characters. But how sad is that! Just one friend! My younger characters, for better and worse, are stuck in these ecosystems that they can’t escape, be that school, sports, summer jobs, or camp, and they both crave escape from those systems and also receive support within them and comfort. My older characters miss those systems sometimes. I think that is part of what the protagonist of “Here Preached His Last” is dealing with; working at this high school and coaching the soccer team, she is on the outside looking in and that’s how she feels in her marriage too. This is all to say, yes, this continuum is always on my mind. My teen characters imagine what they will be as an adult, how they will overcome their flaws and fears. My adult characters wonder what to do now that they’re thirty-five and as flawed and fearful as ever.

JB: Selfishly, I want to ask about “The Disneyland of Mexico,” which features a complicated girl in her own right, but also one of the more melancholic moments in Cassandra. There’s so much overlap of puberty, isolation/alienation, and obligation—to act on sexual impulses, to remain chaste, to “behave,” as we see in the triangulation of Gabi and María, the respective host mother and host sister characters, and the narrator. Can you talk a little about how this story came to life, the inspiration behind it?

GEK: “The Disneyland of Mexico” is the most autobiographical story of the whole book, which isn’t to say that most of it isn’t made up, but it draws on a lot of my own experiences. I lived in Pachuca, Mexico, for a summer when I was sixteen, kissed a boy for the first time, struggled to speak Spanish, went to an abandoned amusement park. And I did dust a bunch of ceramic angels every day and my host mother did destroy all of my underwear through overzealous bleaching. Isolation is a theme of the story, for sure, because I was thinking about that experience of being surrounded by people with no idea what they are saying. It’s exhausting to live that way, straining every moment to understand what is happening and what you should be doing. For me, this story marks an important moment in my journey as a writer. I had been trying to write it for months and it wasn’t working and I decided to try writing it in the second person, which I had never tried before, because the second person felt alienating, which was the experience I wanted to communicate. The second person is also all commands, e.g., “You do this, you do that” and for a while commands, spoken slowly, were the only Spanish I understood. It was the first time that I had solved a narrative problem by deliberately trying a new, more challenging, technique, rather than sort of stumbling around using tools but not perhaps fully aware of why.

JB: I’m interested in whether the drafting of “Jackfruit” felt markedly different from the stories in Cassandra. Post publication, how has your approach to short stories evolved? Do you feel more at home in them than ever, or are you ready to shirk them for the dark side (novels)?

GEK: I wouldn’t say it felt markedly different. I wrote the first few drafts of “Jackfruit” a few years ago and it wasn’t working so I stuck it in a folder and forgot about it for a while. A lot of stories go to the “this isn’t working” folder and then if I am still thinking about that story in another few months or years, out of the folder it goes to be poked at again. For “Jackfruit,” that time away let me see that I had been massively overthinking it, adding explanations where they weren’t needed, trying to simply do too much. I was gilding the jackfruit! More broadly, post publication I still love short stories. I am still writing short stories. I do sometimes think “gosh, have I done this already? Is this more of the same?” but then I think, well, if it is a question that is still bothering me, if it is still a craft challenge, then I’m not done with it, whatever it may be. As for the demon novel, yes, I am dancing with that devil, so we’ll see what happens. But I hope to write short stories for as long as I’m writing.

JB: I love asking this question because I am a serially nosy person: What aspects of your work, be it your process or the content itself, do you wish you got to talk about more but don’t because people don’t often ask?

GEK: For the most part, I wouldn’t say there is anything that I wish people would ask me. If anything, I am absolutely amazed every time that the interviewer has taken the time to really think about something I wrote and ask questions that surprise me. I will say, I do appreciate when an interviewer asks me about my stories without framing the question about womanhood or feminism. Obviously, that is hard to do because those are massive themes in the book. But there are lots of other themes too and I get excited when they get mentioned. I also like when people ask me about humor because I love humorous fiction and it means the world to be even in conversation with those writers.